Lola Reads

Ce sujet est poursuivi sur Lola Reads, vol. 2.

DiscussionsThe Hellfire Club

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

Ce sujet est actuellement indiqué comme "en sommeil"—le dernier message date de plus de 90 jours. Vous pouvez le réveiller en postant une réponse.

3LolaWalser

First, I must read THE book.

HUGS to you, Dr. Urania Newton-Freud! I've been thinking how I need to plop down on your couch (as soon as I collect the greenbacks for the hour) and ask you to explain to me Why Do I ALWAYS ALWAYS ALWAYS Fall For People I Can't Have?

Is it incurable?

HUGS to you, Dr. Urania Newton-Freud! I've been thinking how I need to plop down on your couch (as soon as I collect the greenbacks for the hour) and ask you to explain to me Why Do I ALWAYS ALWAYS ALWAYS Fall For People I Can't Have?

Is it incurable?

4tomcatMurr

If Love's a Sweet Passion,

why does it torment?

If a Bitter, oh tell me

whence comes my content?

Since I suffer with pleasure,

why should I complain,

Or grieve at my Fate,

when I know 'tis in vain?

Yet so pleasing the Pain is,

so soft is the Dart,

That at once it both wounds me

and tickles my Heart.

I press her Hand gently,

look Languishing down,

And by Passionate Silence

I make my Love known.

But oh! how I'm Blest

when so kind she does prove,

By some willing mistake

to discover her Love.

When in striving to hide,

she reveals all her Flame,

And our Eyes tell each other

what neither dares Name.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YLsMwIOwaYc&feature=related

why does it torment?

If a Bitter, oh tell me

whence comes my content?

Since I suffer with pleasure,

why should I complain,

Or grieve at my Fate,

when I know 'tis in vain?

Yet so pleasing the Pain is,

so soft is the Dart,

That at once it both wounds me

and tickles my Heart.

I press her Hand gently,

look Languishing down,

And by Passionate Silence

I make my Love known.

But oh! how I'm Blest

when so kind she does prove,

By some willing mistake

to discover her Love.

When in striving to hide,

she reveals all her Flame,

And our Eyes tell each other

what neither dares Name.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YLsMwIOwaYc&feature=related

5RickHarsch

“The mosque is all awareness. Mind you never go that way.

“The tavern is all ecstasy. So be aware and come!”

Ghalib

“The tavern is all ecstasy. So be aware and come!”

Ghalib

6RickHarsch

“They offer paradise to make up for our life below

“It needs a stronger wine than this

“To cure our hangover.”

Ghalib

“It needs a stronger wine than this

“To cure our hangover.”

Ghalib

7LolaWalser

Thanks for the poetry, Murr and Rick.

I still haven't read A book.

I still haven't read A book.

10Existanai

The reason for the forum's season is sorely lacking.

Can we perhaps goad you into review stacking?

Can we perhaps goad you into review stacking?

11LolaWalser

Where am I? Who are you? What's this thread about? I heard noises, there was a crash, and a sound like a Zeppelin leaking gas, then a purple flash... and then I don't remember anything...

13SilentInAWay

Shhhh....Lola's reading!!

14LolaWalser

I READ A BOOK!

Alert the press...

Believing that the best thing for inflated expectations bubble is a quick, firm needleprick of hope-dashing reality, I hereby announce my successful completion of Gerard Jones' (whoever he is) Men Of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, a book about. The business. Of comics. Start redexing this thread, its hellish descent has just begun...

It is mostly about Superman, his hapless creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and their hair-raising incompetence at making a buck off a product that made millionaires of hundreds of others, but the background is nicely padded with an overview of the rambunctiously seedy pulp industry, and other superheroes as they zoom in on the trail of Superman's cape, mostly ridiculous, some sublime. I mention with admiration that I never knew so many Jews made the comics (along with Hollywood, this clearly makes them US and world entertainers supreme). I didn't even know Jack Kirby was once Jake Kurtzberg, for instance. Outside art to the outsiders, marginal culture to the marginals.

I also discovered--echoing Peter's (copyedit's) experience of the Marvel gang in another thread --that anyone writing or drawing comics is most likely an extraordinarily boring person with a dreary life to whom nothing ever happens. One notable exception would be Dr. William Moulton Marston, psychologist, lawyer, lie detector inventor, happy polygamist, househusband and creator of The Wonder Woman--all those bondage scenes in her comics, it turns out, were inserted for the good of young men's mental health. Thank you, Doc!

In sum, a good book for an older, unsentimental comics geek.

Alert the press...

Believing that the best thing for inflated expectations bubble is a quick, firm needleprick of hope-dashing reality, I hereby announce my successful completion of Gerard Jones' (whoever he is) Men Of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, a book about. The business. Of comics. Start redexing this thread, its hellish descent has just begun...

It is mostly about Superman, his hapless creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and their hair-raising incompetence at making a buck off a product that made millionaires of hundreds of others, but the background is nicely padded with an overview of the rambunctiously seedy pulp industry, and other superheroes as they zoom in on the trail of Superman's cape, mostly ridiculous, some sublime. I mention with admiration that I never knew so many Jews made the comics (along with Hollywood, this clearly makes them US and world entertainers supreme). I didn't even know Jack Kirby was once Jake Kurtzberg, for instance. Outside art to the outsiders, marginal culture to the marginals.

I also discovered--echoing Peter's (copyedit's) experience of the Marvel gang in another thread --that anyone writing or drawing comics is most likely an extraordinarily boring person with a dreary life to whom nothing ever happens. One notable exception would be Dr. William Moulton Marston, psychologist, lawyer, lie detector inventor, happy polygamist, househusband and creator of The Wonder Woman--all those bondage scenes in her comics, it turns out, were inserted for the good of young men's mental health. Thank you, Doc!

In sum, a good book for an older, unsentimental comics geek.

15LolaWalser

The reading, it continues apace!

I am still pursuing my "Read it or Lose it or THEN lose it" campaign, where I grab a book more or less at random. The more or less random recent reads:

Contes et nouvelles en vers by Jean de La Fontaine--not the La Fontaine we read in school! A good proportion are versified tales from Boccaccio and all feature sexual shenanigans and humour of the broadest kind--the kind that would get you censored on TV to this day. Example--and don't say I didn't warn you--an old husband with a frisky young wife suffering jealous torments dreams one night that the Devil is putting a ring on his finger and tells him that as long as he keeps it on, his wife will be faithful. He awakes to find his finger up hers you-know-what. (L'anneau de Hans Carvel)

And so forth with froth.

Les amants de Byzance by Mika Waltari (1952)

A tale of the fall of Constantinople, covering about six months up to Doomsday, the waiting, the raids, the siege. A mysterious stranger, Johannes Angelos, half Greek, half Latin, erstwhile slave to the Sultan, arrives "to die defending the city" and falls in love with a high born lady once meant for the Emperor. Everyone dies. Recommended for the younger teen by my inner chile.

L'ancre de miséricorde by Pierre Mac Orlan (1941)

A pirate adventure story with all the ships anchored in the port! That's my main peeve. It is not more boring than Treasure Island, though.

La guerre des boutons by Louis Pergaud (1913)

Two bands of boys from hostile neighbouring villages, the feud dating centuries back to the case of One Sick Cow, are engaged in total war, meeting regularly for skirmishes where rocks and stick fly, and the captives are stripped and their clothes de-buttoned, forcing victims to return home shamed and sometimes naked. Wonderful language, sparking with dialect and juvenile argot, wholly Rabelaisian (Pergaud warns in his preface no concessions are made to "decency" in illustrating the kids' lingo and mores), reminiscent of the (much later) Lord of the flies, but funnier and somewhat less vicious. Pergaud was killed in WWI, at age 33.

16pgmcc

#15 Lola

I hadn't realised the War of the Buttons was a French novel. An Irish version of the story was made into a very funny film starring Colm Meaney. The first few minutes are available to view here. In fact, now that I look at the lists of captions on YouTube it looks like the whole film is there.

Having just watched the opening scenes I note the Irish film credits state it was based on a French film called La guerre des boutons.

I hadn't realised the War of the Buttons was a French novel. An Irish version of the story was made into a very funny film starring Colm Meaney. The first few minutes are available to view here. In fact, now that I look at the lists of captions on YouTube it looks like the whole film is there.

Having just watched the opening scenes I note the Irish film credits state it was based on a French film called La guerre des boutons.

17LolaWalser

Interesting. Looks like there are at least two earlier French adaptations too (the photo on my book's cover is from the later one, I guess). Haven't seen any of the above.

18tomcatMurr

Treasure Island boring? My inner chile protests most vehemently at this appellation.

20tros

Almost as boring as Hugo. Or Dickens. Or Tolstoy. Or...

Maki's right. I should have said; Not nearly as boring as...

Maki's right. I should have said; Not nearly as boring as...

21LolaWalser

#18

What can I tell you, cat, me 'n Stevenson aren't exactly well-matched. Not that I hate him! Gosh no, and there's plenty of him (Arabian night stories esp.) I've quite enjoyed. The Suicide Club! Excellent. Treasure Island--not so much. To be fair, it's been decades.

What can I tell you, cat, me 'n Stevenson aren't exactly well-matched. Not that I hate him! Gosh no, and there's plenty of him (Arabian night stories esp.) I've quite enjoyed. The Suicide Club! Excellent. Treasure Island--not so much. To be fair, it's been decades.

22Makifat

It was only in the past couple of days that I read somewhere (on LT perhaps?) the lament that Stevenson is now regarded as primarily a children's author. That's rather a pity. There's a lot of decent Stevenson that goes way beyond Treasure Island.

It's hard to imagine the existence of The Picture of Dorian Grey without The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

It's hard to imagine the existence of The Picture of Dorian Grey without The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

23LolaWalser

I loved The black arrow. Read it many times. I have a copy of Kidnapped knocking about too, although I fear its time in my life is long past.

Also reads:

***

***

Un Noël de Maigret (Maigret's Christmas) by Georges Simenon. Three early-ish stories happening on Christmas (for evil knows no religion!), only the first one, about a Santa Claus' mysterious and likely sinister visit to a sick child's room, featuring Maigret. The second one was quite exciting, with policemen stationed in their headquarters following helplessly on the city map the trail of a child following a killer--or maybe the trail of a killer following a child. The third one was funny (in the dour way Simenon is sometimes funny). In a bistro about to close, filled with loners (who else would be there on Christmas?), one of the lonely men suddenly commits suicide. The event shakes up one of the whores present who decides to continue her evening in the human throng, instead of going home. In a cafe she observes a couple of sleazebags putting the make on an obvious novice, fresh off the bus, and stages an incident that ends up in general police arrest. The women are jailed together and the veteran whore gives a piece of her experienced mind to the young one. It's the sweetest Simenon ever gets. I read him rarely, almost grudgingly. I don't like him very much--I don't want to like him either. But damn, there's quality in him.

The spoke by Friedrich Glauser.

I've no trouble liking Glauser, a druggie and a crazy who spent lots of time in sanatoriums, although he's probably less deserving than Simenon. However, he also suffers from being read in translation, his juicy Bernese Swiss simply can't work its effect in English dress. But something gets through: the variety and the plastic form of people, usually small towners and rustics, peasants, rural no-goodniks, young delinquents, girls who strive, matrons content or disappointed... In this book, someone is murdered using a filed bicycle spoke, and Sergeant Studer (once upon a time humiliated and demoted from inspectorship, but going about his business of being a policeman coolly and unswervingly) puts together the picture of what happened through lots of talk and a few casual observations.

(I'm the world's worst mystery reader, forgetting "clues" as they hit me between the eyes, and hardly ever caring for whodunnit. So, it is not from nor for that angle that I read these--just a warning to possible follow-uppers.)

Also reads:

***

***

Un Noël de Maigret (Maigret's Christmas) by Georges Simenon. Three early-ish stories happening on Christmas (for evil knows no religion!), only the first one, about a Santa Claus' mysterious and likely sinister visit to a sick child's room, featuring Maigret. The second one was quite exciting, with policemen stationed in their headquarters following helplessly on the city map the trail of a child following a killer--or maybe the trail of a killer following a child. The third one was funny (in the dour way Simenon is sometimes funny). In a bistro about to close, filled with loners (who else would be there on Christmas?), one of the lonely men suddenly commits suicide. The event shakes up one of the whores present who decides to continue her evening in the human throng, instead of going home. In a cafe she observes a couple of sleazebags putting the make on an obvious novice, fresh off the bus, and stages an incident that ends up in general police arrest. The women are jailed together and the veteran whore gives a piece of her experienced mind to the young one. It's the sweetest Simenon ever gets. I read him rarely, almost grudgingly. I don't like him very much--I don't want to like him either. But damn, there's quality in him.

The spoke by Friedrich Glauser.

I've no trouble liking Glauser, a druggie and a crazy who spent lots of time in sanatoriums, although he's probably less deserving than Simenon. However, he also suffers from being read in translation, his juicy Bernese Swiss simply can't work its effect in English dress. But something gets through: the variety and the plastic form of people, usually small towners and rustics, peasants, rural no-goodniks, young delinquents, girls who strive, matrons content or disappointed... In this book, someone is murdered using a filed bicycle spoke, and Sergeant Studer (once upon a time humiliated and demoted from inspectorship, but going about his business of being a policeman coolly and unswervingly) puts together the picture of what happened through lots of talk and a few casual observations.

(I'm the world's worst mystery reader, forgetting "clues" as they hit me between the eyes, and hardly ever caring for whodunnit. So, it is not from nor for that angle that I read these--just a warning to possible follow-uppers.)

24tomcatMurr

forgetting "clues" as they hit me between the eyes, and hardly ever caring for whodunnit

lol

me too.

lol

me too.

25LolaWalser

Mystery twins!

For you, Murr, I`d recommend Glauser`s In Matto`s realm (should you chance upon it, rather than expressly getting it). It distills Glauser`s madhouse experiences; in some ways it`s like The cabinet of Dr. Caligari, in words.

For you, Murr, I`d recommend Glauser`s In Matto`s realm (should you chance upon it, rather than expressly getting it). It distills Glauser`s madhouse experiences; in some ways it`s like The cabinet of Dr. Caligari, in words.

26pgmcc

The mention of the French books and films reminds me that I'm off to France on Friday for ten days. Just thought I'd say! :)

27Nicole_VanK

Enjoy.

28LolaWalser

#26

Oh, I hate you!

NO, no, I mean, "enjoy"! :)

Oh, I hate you!

NO, no, I mean, "enjoy"! :)

29tros

For the Stevenson deprived, an interesting collection of his lesser known tales.

R. L. Stevenson

The Fabulous Raconteur

Forgotten Classics of Mystery Volume 4

http://www.librarything.com/work/258806/summary/19555435

The Suicide Club

The Young Man with Cream Tarts

The Physician and the Saratoga Trunk

The Adventure of the Hansom Cab

Thrawn Janet

The Pavilion on the links

The Sire de Maletroit's Door

The Wrecker

R. L. Stevenson

The Fabulous Raconteur

Forgotten Classics of Mystery Volume 4

http://www.librarything.com/work/258806/summary/19555435

The Suicide Club

The Young Man with Cream Tarts

The Physician and the Saratoga Trunk

The Adventure of the Hansom Cab

Thrawn Janet

The Pavilion on the links

The Sire de Maletroit's Door

The Wrecker

30pgmcc

#27 Thank you!

#28 Thank you! I hate myself sometimes too; but I'm still going to France on Friday. ;)

Have a lovely Easter. Hopefully I will have had a chance to do some reading and will have something worth contributing.

Bon chance, mes amis!

#28 Thank you! I hate myself sometimes too; but I'm still going to France on Friday. ;)

Have a lovely Easter. Hopefully I will have had a chance to do some reading and will have something worth contributing.

Bon chance, mes amis!

31pgmcc

#29 Thrawn Janet

"Thrawn". That's a word I haven't heard in years. It is common enough in Northern Ireland where I grew up, but I moved to Dublin in 1982 and it doesn't seem to be used here at all.

"Thrawn". That's a word I haven't heard in years. It is common enough in Northern Ireland where I grew up, but I moved to Dublin in 1982 and it doesn't seem to be used here at all.

32LolaWalser

***

***

Looking backward by Edward Bellamy (1887)

I'm startled by how pleasant it was to read this literarily unprepossessing "novel" in the beautiful LEC edition. This does not bode well for my ability and willingness to consume electronic "books". I was looking forward (and backward) to chapter headings with illustrations in always different colour, admiring the letterpress type (so black, so thick, so deep), weighing the book in my hand (solid, yet light), noting the modernist square shape... all of these are signs and messages in themselves, unnecessary, to be sure, in receiving Bellamy's communication, but somehow enhancing it and helping it along. Call me a sybarite, but I'd rather have that than not.

Bellamy's communication is his solution for the ills of his society, set 113 years after his day. And it's communism. The most astonishing feature of his utopia is the basic one--complete abolition of the market and trade.

The State--that is, the collective of citizens--is the sole owner and overseer of industry. All citizens are members of the "Industrial Army" until the age of 45, when they retire (and as Bellamy describes in a disarming vision, their life, far from ending, actually begins). All citizens receive the same fixed amount of credit (not "pay"), whatever their function and profession. Private inheritance is done away with, on death all possessions revert to the state. Work hours are light for difficult jobs, longer for the pleasant ones, and vacations abound past what Europe ever dreamed of. Many other innovations are mentioned, regarding environment, housing, religion, shopping, women, the sick etc.

Knowing nothing about Bellamy himself, it becomes clear that he was deeply affected by the poverty, misery and social upheavals he witnessed, labour unrest, strikes and terrorist anarchism especially. The latter is discussed as "the red flag party", which, it turns out, was subsidised by capitalists to obstruct reform.

All in all, a very interesting read on a perennial theme--what makes a just society?--and a nicer, more humane utopia than any other from that period I've read.

Le chant d'Orphée selon Monteverdi (The song of Orpheus according to Monteverdi) by Philippe Beaussant

Monteverdi, the man who married music and drama, is my greatest musical hero, a creator of astonishing, unique imagination and innovator who convinces me that everything is discovered only once, the first time, the followers only develop. All 400 years of opera are in his Orpheus, like a tree in a seed. I was finally able to squeeze in two consecutive hours for a joint listening-reading session of Monteverdi's L'Orfeo and Beaussant's culturological analysis of it, and the experience of having another consciousness guide my ear was wonderful. Monteverdi's patrons, the lords of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga and his intellectual wife Isabelle d'Este, were discussed, the art that embellished their palace (lots of Mantegna), the academies of scholars and amateurs flourishing at the time throughout Italy, the example of Florence, where the first something-like-opera was performed in 1600, Jacopo Peri's Euridice (the myth of Orpheus again), and the neoplatonism that suffused the words of Alessandro Striggio, Monteverdi's librettist, and cast the old myth in new philosophical clothes. Last and least, there is some musicological analysis, just enough to draw attention to Monteverdi's new devices, his amazing emotional expressivity, the colouring of Orpheus with A minor, say, and the brutal contrast to it of Charon's F major, in the dank and oppressive underworld, the frank subjection of words to music, the cross-over employment of Italian dances and Dutch polyphony, the super-fine dynamics...

Loved the last sentence: "In Orpheus Monteverdi midwives Renaissance and the newborn is Baroque." (Hey, it's not my fault English doesn't have the perfect translation for "faire accoucher"!)

Rare fun was had by me.

33tomcatMurr

that sounds divine. Monteverdi is also one of my heroes. I'm listening to the Vespers right now.

34LolaWalser

Loooove them. Which version? That was the first Monteverdi I heard live, and in a church too, as our Lord ordains. Check out Handel's Marian cantatas too. The Virgin could be a Muse...

35tomcatMurr

John Elliot Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir. Philip Langridge. RIP.

36LolaWalser

Have that!

37SilentInAWay

Me too!! -- believe it or not, its been in my CD changer for the last few months!!

38LolaWalser

Monteverdi >>> Beatles

40LolaWalser

Yeeeeees, Emmanuelle Haim and her ensemble did a jazzed-up Monteverdi too... being Monteverdi's bitch I of course bought it, but old-timey is the best for me.

Have the McCreesh too. Solid, less sparky than Gardiner.

Have the McCreesh too. Solid, less sparky than Gardiner.

41LolaWalser

I can't believe Silent isn't picking up on the Beatles diss. I'm losing my touch...

Maybe if I bold it?

Monteverdi>>>Beatles

Maybe if I bold it?

Monteverdi>>>Beatles

42SilentInAWay

That was a diss? I thought you were speculating on the schizophrenic juxtapositions within my CD changer (where >>> is the sound of changing disks):

Monteverdi >>> Beatles >>> Morton Feldman >>> Gonzalo Rubalcaba >>> Allman Brothers >>> Pierre de la Rue >>> Fritz Wunderlich >>> Les Claypool >>> Peter Gabriel >>> Eliot Carter >>> Jethro Tull >>> The Dead Weather >>> Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan >>> Heinrich Schütz >>> Morten Lauridsen >>> Florence Foster Jenkins >>> Toshiko Akiyoshi >>> Meshell Ndegeocello >>> Miles >>> Mingus >>> Monk >>> Mahler >>> Booker T & the MGs >>> Wayne Krantz >>> Mike Keneally >>> Mitsuko Uchida >>> Dead Kennedys >>> Gerald Finley >>> Toru Takemitsu

Monteverdi >>> Beatles >>> Morton Feldman >>> Gonzalo Rubalcaba >>> Allman Brothers >>> Pierre de la Rue >>> Fritz Wunderlich >>> Les Claypool >>> Peter Gabriel >>> Eliot Carter >>> Jethro Tull >>> The Dead Weather >>> Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan >>> Heinrich Schütz >>> Morten Lauridsen >>> Florence Foster Jenkins >>> Toshiko Akiyoshi >>> Meshell Ndegeocello >>> Miles >>> Mingus >>> Monk >>> Mahler >>> Booker T & the MGs >>> Wayne Krantz >>> Mike Keneally >>> Mitsuko Uchida >>> Dead Kennedys >>> Gerald Finley >>> Toru Takemitsu

43LolaWalser

Florence Foster Jenkins

lol

lol

44SilentInAWay

I was wondering how quickly you'd catch that.

For those of you who have never had the pleasure of hearing The Glory of the Human Voice

For those of you who have never had the pleasure of hearing The Glory of the Human Voice

45marietherese

Oooh, which Finley and Akiyoshi disks? Wondering about the Takemitsu too.

FFJ is a standard party recording for geeky opera buffs. Nothing is guaranteed to lead to heavy drinking and raucous fun sooner. Either that or the party clears out immediately.

FFJ is a standard party recording for geeky opera buffs. Nothing is guaranteed to lead to heavy drinking and raucous fun sooner. Either that or the party clears out immediately.

46Makifat

Back in my carefree younger days, we used Florence Foster Jenkins to clear out the record store at closing time....

47tomcatMurr

Mockers! The woman was a genius! GENIUS! The vibrato, the control! The frocks!

When we've all had a bit more to drink, I shall treat you all to my FFJ impersonation.

When we've all had a bit more to drink, I shall treat you all to my FFJ impersonation.

48SilentInAWay

45> Finley::Akiyoshi::Takemitsu:: here are the ones currently in my CD changer ::

Gerald Finley w/ Julius Drake (piano) :: Schumann :: Dichterliebe & other Heine Settings :: Hyperion

Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra Featuring Lew Tabackin :: Desert Lady-Fantasy :: Columbia

Takemitsu (1) :: Chamber Music :: Aiken (flute) / Toronto New Music Ensemble :: Naxos

Takemitsu (2) :: Riverrun, Water-Ways, etc. :: Crossley (piano) / London Sinfonietta / Knussen :: Virgin Classics

A Confession: FFJ is not really in my CD changer right now. In fact, she can't be -- I only own Glory in a vinyl copy of late 70s vintage. I just threw her into the mix to see what happens.

Also, the schizo-positioning of the disks is really meaningless -- I rarely play disks in the changer in sequence. I'll either listen to the one I just loaded, or I'll set it up so something I'm currently interested in repeats ad nauseum. So mood-swings from, say, Uchida's Schubert to the Dead Kennedys are highly unlikely.

Gerald Finley w/ Julius Drake (piano) :: Schumann :: Dichterliebe & other Heine Settings :: Hyperion

Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra Featuring Lew Tabackin :: Desert Lady-Fantasy :: Columbia

Takemitsu (1) :: Chamber Music :: Aiken (flute) / Toronto New Music Ensemble :: Naxos

Takemitsu (2) :: Riverrun, Water-Ways, etc. :: Crossley (piano) / London Sinfonietta / Knussen :: Virgin Classics

A Confession: FFJ is not really in my CD changer right now. In fact, she can't be -- I only own Glory in a vinyl copy of late 70s vintage. I just threw her into the mix to see what happens.

Also, the schizo-positioning of the disks is really meaningless -- I rarely play disks in the changer in sequence. I'll either listen to the one I just loaded, or I'll set it up so something I'm currently interested in repeats ad nauseum. So mood-swings from, say, Uchida's Schubert to the Dead Kennedys are highly unlikely.

49Existanai

All Florence needed was a great voice coach.

50Existanai

>I shall treat you all to my FFJ impersonation.

Only if you dress the part!

>my CD changer

We use iPods for that now. ;)

Seriously, I miss having a really good CD changer; I looked around for a used one but gave up, partly because I couldn't find the kind I wanted at a reasonable price, partly because I couldn't really fit it into my cramped apartment anyway. Except for one or two Yamaha warhorses and the like, they're not even manufactured anymore - it's easier to buy a turntable.

Only if you dress the part!

>my CD changer

We use iPods for that now. ;)

Seriously, I miss having a really good CD changer; I looked around for a used one but gave up, partly because I couldn't find the kind I wanted at a reasonable price, partly because I couldn't really fit it into my cramped apartment anyway. Except for one or two Yamaha warhorses and the like, they're not even manufactured anymore - it's easier to buy a turntable.

51tomcatMurr

oh of course! Dressing up is half the fun!

52Existanai

Murr, as our most prominent Russophile, are you acquainted with the tradition of Russian song?

53LolaWalser

#48

I knew you wuz cheatin'! No one can listen to such a mess without their head exploding.

Jenkins Flo vs. Sumi Jo... ah, I feel a ditty coming on.

I knew you wuz cheatin'! No one can listen to such a mess without their head exploding.

Jenkins Flo vs. Sumi Jo... ah, I feel a ditty coming on.

54SilentInAWay

50>

My iPod is, if anything, more eclectic than my changer. It pretty much stays in my car, though, except when I travel (my commute to work is about an hour each day, so it sees pretty heavy usage). I've put somewhere between 600 and 700 CDs on it, yet still often find myself in the mood for something I have at home...

52>

Ooh, thanks for that, E. --- I love Anna Russell, but know her almost entirely from audio recordings (again, originally vinyl). I never thought of looking her up on YouTube -- she's as amusing to watch as she is to listen to.

My iPod is, if anything, more eclectic than my changer. It pretty much stays in my car, though, except when I travel (my commute to work is about an hour each day, so it sees pretty heavy usage). I've put somewhere between 600 and 700 CDs on it, yet still often find myself in the mood for something I have at home...

52>

Ooh, thanks for that, E. --- I love Anna Russell, but know her almost entirely from audio recordings (again, originally vinyl). I never thought of looking her up on YouTube -- she's as amusing to watch as she is to listen to.

55Existanai

Silent, that clip is from VAI Music, which has released a couple of DVDs of Anna Russell - their site is linked under the videos, if you didn't already notice.

Re: iPods (you know I was ribbing) I find that my ripped or downloaded tracks, even when heard through high-end headphones, sometimes carry static and other glitches not on the CD; and nothing quite replaces listening through a pair of speakers that have plenty of detail.

Re: iPods (you know I was ribbing) I find that my ripped or downloaded tracks, even when heard through high-end headphones, sometimes carry static and other glitches not on the CD; and nothing quite replaces listening through a pair of speakers that have plenty of detail.

57LolaWalser

**

**  **

**  **

**

Vor Bildern by Robert Walser is a small, appetising selection of Walser's sketches on specific paintings, in prose and poetry, where the paintings are often only framing other topics--a tiff with a landlady, a walk in the forest--or serve as departure points for drama (as the fantasy of a conversation with Manet's Olympia)--or undergo that strange Walserian analysis in which everything except the primary object seems to be discussed, and then a sudden connection or insight clicks into life, like a revelation. The liveliness of the text is owed to his mildly zany mannerisms, the shifting of pace, the digressions, and the irruptions of the personal--such as the last sentence in the otherwise well-behaved sketch on Brueghel the Older--"Beautiful women are ornamenting the Promenade by their presence, and I'm sitting here and writing?", which is like someone jumping away from the table just as they brought in the dessert, and declaring he must live, live, LIVE!

Il dolore by Giuseppe Ungaretti leaves me cold as poetry, and chills as testament to his suffering. The collection is very short, and most of the pieces in it are short (one a single broken line, a desperate shout: "And I love you, I love you, and it is a constant tearing!") as if the voice were being strangled. Two tragic premature deaths, of his brother and son, dominate the first part, and continue to echo in the grieving war pieces, and the hope for god (Jesus' return), and renewal of innocence.

Le centaure dans le jardin (The centaur in the garden) by Moacyr Scliar didn't fulfill by the end all the hopes it raised in the beginning. A centaur, called Guedali, is born in an otherwise unremarkable Jewish-Brazilian family eking a farming life out in the sparse countryside. The problems of a human with the lower body of the horse are presented quite realistically--the dietary and hygienic concerns, the complications of horse-sized sexuality, the question of whether a centaur can be a good Jew (one hopes circumcision is the step in right direction). After a move to the city (preceded by my favourite sentence in the whole book, something about how in a city no one will notice how unusual Guedali is) and escalating family tensions, Guedali runs away, joins a circus, falls in love with a mysterious stranger he secretly spies on, and eventually meets a girl-centaur, Tita, who becomes his mate. For a while they enjoy a pastoral idyll, among friendly old ladies, galloping and having hot horsey sex all the time, but then Tita grows dissatisfied, yearns to be normal, live in the city... and they start exploring the possibility of species-change, which takes them to a plastic surgeon in Morocco. I'd rather not retell the whole plot--there's quite a bit of it, no one need worry about philosophical longueurs in this book--and say only that the transformations of the characters and their surroundings took up too much in descriptive detail and not enough in motivation. I was especially intrigued by the conflict between the emerging yuppie class and the leftists and the question where our centaurs placed, as well as by the position of Jews in Brazil--was it a promised land, where even Jews could ride (one of Scliar's epigraphs remind us that "There never were Jews on horses"--(i.e. noble), or was it a painful trap, where a Jewish boy better fantasise himself out of reality?

Would love to hear opinions from whoever read this.

After nature was Sebald's first published book, and sounds just like his other, except the sentences are broken up into patterns signifying "poetry". No metaphors, no fancy epithets, no bells and whistles, just his serious, poised cadences informing us about Matthias Grünewald, a mysterious Renaissance painter with a talent for grotesque and visual representations of pain; Georg Steller, a scientist and one of many Germans in intellectual professions who emigrated to Russia--Steller because he wanted to take part in the Bering expedition sponsored by Catherine the Great; and Sebald's family.

I also read two borrowed Reginald Hills, Dialogues of the Dead, a feast for any word puzzle nerd, brimming with excellently used literary references and allusions, and Midnight fugue, which I've already almost entirely forgotten... except there's Bach in it. I really like this Reginald Hill person, I like his detectives, and I like the nowts and owts and many colourful expressions people apparently use in Yorkshire ("getting up at sparrowfart"--I hope I remember that).

Speaking of detectives, I watched the three episodes of the first season of BBC's 2010 "Sherlock" series, with Bernard Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman as Sherlock and Watson and I give it all four thumbs up. Unevenly good writing, some doubtful casting (come on--THAT's Moriarty?!) but overall a successful concoction based on an idea (bringing Sherlock into 21st century) that at first sounds terrifying to any fan. So very glad 221B Baker Street is open for business again. And this time all the gay may come out to play!

58theaelizabet

Sadly, I can't speak to your reading choices, but I can agree with your take on the new Sherlock series. Classy and smart, with a great update of the Watson character. My family and I loved them and can't wait until the new episodes begin in August.

59LolaWalser

Oh, so cool to meet another fan! Yeah, I love this Watson (I've seen Martin in The office and The black books too)--he is such a fine person, solid, good, brave, but I like best his unassuming-ness and shyness--how he conveys them, like when he shifts from one foot to another, or pulls his head between his shoulders, or looks away, from side to side--there is something touchingly vulnerable about him.

I've never seen Cumberbatch before, but his presence and acting make you think he was born to play this. Excellent, excellent casting both of them.

I've never seen Cumberbatch before, but his presence and acting make you think he was born to play this. Excellent, excellent casting both of them.

60LolaWalser

***

***  ***

***  ***

***

A time to keep silence by Patrick Leigh Fermor caught my attention because of his mention of Huysmans (he was reading him a lot at the time, Fermor notes), whose En route I recently read. Both Huysmans and Fermor write about their stays as guests in Trappist monasteries; Fermor also visited Solesmes (as did Huysmans), and observed the remnants of Byzantine monasteries and churches in Cappadocia. Well--whatever Fermor thought about or carried away from Huysmans is completely invisible in this tepid account, as is any personal engagement or disengagement with religion. I rarely had such a strong feeling of themes and opinions being actively AVOIDED, although, considering that Fermor might have been a Protestant or atheist seeking hospitality (repeatedly) among Catholics expressly withdrawn from the world in order to practise complete devotion, perhaps that is not so difficult to excuse. He does wonder briefly about the monkish life in regard to Freudianism (aren't they all horribly repressed, sexual bombs ticking away?), but in general, the monks seem to him out-of-this-world calm, benevolent, happy. Fermor himself, while keeping mum on what these retreats may be doing for his immortal soul, expands somewhat on the benefices of silence and quiet for a stressed-out 20th century body: first the discouraging onslaught of fatigue and boredom, the escape into drugged-like sleep, then the restoration of balance, lucidity, vitality. I believe this process has since been widely commercialised, with many a spa offering "the monastery experience".

There's one thing I want to remember from this book. Fermor asks a monk if he can sum up his way of life. The monk thinks for a bit, then asks Fermor if he had ever been in love. Yes, says Fermor. The monk smiles widely. It's exactly like that, he says.

(Associations--ecstatic life, agape, pre-capitalist society, discipline, routine, bare essentials--and in the Trappist tradition, dolorism.)

La Bavolette by Paul de Musset, three stories/romances, first published in 1856. In the first one, set at Sun King's dawn, a poor peasant girl of great beauty and fine character gets to hobnob with aristocrats, defend her (often threatened) honour, and best them all; in the end, possibly, even carrying off the prize of a very special lover--nice of de Musset to keep it ambiguous, Claudine is upright but no prude. In the second story, mistaken identity and a series of drolly vicious incidents eventually lands a young man with a very desirable bride; in the third one, two would-be lovers spend two months separation endangering their relationship through uncalled-for epistolary gyrations--it is never smart to be too witty.

Paul, by the way, was Alfred's elder but much less popular brother, who doted on his cadet, kept his literary flame burning, and even married Alfred's last mistress.

Ferdinand by Louis Zukofsky. This is the first time I read Zukofsky, who was, it seems, above all a poet. Ferdinand is a story, not particularly "poetic" at all, tracing the main course of a life from boyhood to middle age, from pre-WWI Europe to WWII United States. The boy is privileged, growing up on the Riviera, but his parents, busy with statesmanlike affairs, handed him over to a loving aunt and uncle. This may or may not pose some kind of problem for the boy--on the whole, not much. (Until he witnesses his mother's death and manages a smile.) For some annoying reason Zukofsky never identifies Ferdinand's country by name, writing instead "Ferdinand's country", "the capital of his country", which is nothing but silly. The country in question is France, the capital Paris etc. and no, I don't see that this circumlocution matters in any way. In due course, as expected and projected, Ferdinand entered diplomatic service, like his parents and elder brother, and the invasion of France found him in Washington, D.C. This break in his routine life shakes him out of his routine biography, he takes a leave of absence, drives off to meet his aunt and uncle, now old and on the run from Europe, and sets with them on a cross-country jaunt, reaching, by my guess, New Mexico. Maybe Arizona. There he has a dream in which he kills the old people, based on a Native American myth, but is glad to find it was just a dream. The end.

What's in this story? For one thing, a strong sense that none of us knows why we are who we are, where we are, and how we got there.

Bibliographie des fous. De quelques livres excentriques by Charles Nodier is an essay on a handful of more or less certifiably crazy (per Nodier) people who wrote books, or "literary lunatics". They are, in order Nodier mentions them, Francesco Colonna, the author of the macaronic galimatias Hypnerotomachia Poliphili; Guillaume Postel, astronomer, philosopher, and Christian kabbalist who claimed to have discovered a "new Eve", the female Messiah, in an old Venetian nun; Simon Morin, "a poor devil" who figured out that HE was Christ come again, burnt on the stake with his "Pensées" in front of the Notre Dame, while some easy women were being whipped around it, for good measure--this undoubtedly threw yet another pail of cold water on free thinkers, fanatical or not; one Sieur de Mons, from the times of Henry IV, whose Quintessence du quart de rien (The quintessence of a quarter of nothing) and Sextessence diallacticque sound utterly tantalising, but are apparently unfindable. Nodier describes them as the fifth and sixth essence of the absurd, and notes that likely their import is lessened in the times when the absurd runs in the streets (Nodier, let it be noted, is squarely of the mid-19th century). Last but not least, Bluet d'Arbères, self-styled comte de Permission, at various times shepherd, gunner, prophet, hermit, buffoon, and always, by his own account, illiterate, somehow yet managed to publish books, which, in OUR day and age, is really nothing remarkable. Besides, Mohammad did it first. One site I managed to find talks of Bluet's "luxuriant visions, etymological games, and parables of religious character", and then of the interest his hallucinations have for neurobiology.

So now to the question of lunacy in art. In short, how does one tell? It isn't enough or even essential, that something "makes no sense", because nonsense exists as a playful genre on its own. Seems to me that mad art is whatever is produced by mad people, and nothing else. (As for the question of how one can tell mad people from the non-mad, always... hell if I know.)

In searching for sources given in Nodier, I came across this site, dedicated to "lunatics in literature" and others of the kind: I.I.R.E.F.L. (full title: : Institut International de Recherches et d’Explorations sur les Fous Littéraires, hétéroclites, excentriques, irréguliers, outsiders, tapés, assimilés, sans oublier tous les autres…)

This post shows some graphic and plastic "sick art", but noted mainly for further reference:

Marcel Réja, "L'art malade : dessins de fous" (1901)

And a ref to an American "expert on kooks":

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donna_Kossy

61Makifat

60

Wonderful post. It is regrettable that so little of Nodier is available to the monoglot English-speaker (i.e., me).

Wonderful post. It is regrettable that so little of Nodier is available to the monoglot English-speaker (i.e., me).

62tomcatMurr

yes, ditto. I would love to read that Nodier. I love those kind of crazy mad artists, and the whole question of where do you draw the line. Isn't it crazy to write a whole novel with no letter 'e' for example? Crazy, or just a technical challenge? Or a crazy technical challenge.

Coudln't we get existanai to write a spurious De Mons work? For the Hellfire Press?

Coudln't we get existanai to write a spurious De Mons work? For the Hellfire Press?

63dcozy

Or maybe it's crazy to write a novel that earnestly aims to capture the pangs and pains of first love, the humiliations and pleasures of aging, or the feeling one gets watching the sun, in winter, set behind a stand of barren trees—even if those novels are employing all the vowels the language hasn to offer.

64LolaWalser

#61

You know, that is a pity and a surprise too, because Nodier is really good. I don't understand how come someone didn't jump to translate him already. Especially for your tastes, Mak, not only did he write quite a bit of supernatural horror (he introduced Slavic tales of vampirism to the West, as well as Slavic folklore etc. he encountered working as a librarian in Ljubljana), but he was also a fanatical bibliophile, bookshop-crawler and collector, and wrote lots about these passions. Somewhere in the essay on the literary crazies he notes that every scribomane, no matter how crazy, can count on eventual interest and championship of a no less crazy bibliomane. :)

He also held a literary salon (in a library), entertaining Hugo, Sainte-Beuve, de Vigny, Alfred de Musset, Dumas dad--every single name warranting an entry in the Who's Who of Romanticism.

#62

Cat, your people should talk to my people. So what if the bookworld is in crisis. So what if The Book is dead. So what if the publishers are scrambling for survival. I say we buy a printing press and get down to business.

Coudln't we get existanai to write a spurious De Mons work?

He's nimble and fast, but if I aim well, I could probably fell him with a well-chosen tome, tie in front of a computer, and threaten with starvation and/or "damnation without relief", as Rowan Atkinson says. I have a feeling he works best confronted with deathlines. :)

#63

Like in that Poe story, everyone is mad--except the writer.

You know, that is a pity and a surprise too, because Nodier is really good. I don't understand how come someone didn't jump to translate him already. Especially for your tastes, Mak, not only did he write quite a bit of supernatural horror (he introduced Slavic tales of vampirism to the West, as well as Slavic folklore etc. he encountered working as a librarian in Ljubljana), but he was also a fanatical bibliophile, bookshop-crawler and collector, and wrote lots about these passions. Somewhere in the essay on the literary crazies he notes that every scribomane, no matter how crazy, can count on eventual interest and championship of a no less crazy bibliomane. :)

He also held a literary salon (in a library), entertaining Hugo, Sainte-Beuve, de Vigny, Alfred de Musset, Dumas dad--every single name warranting an entry in the Who's Who of Romanticism.

#62

Cat, your people should talk to my people. So what if the bookworld is in crisis. So what if The Book is dead. So what if the publishers are scrambling for survival. I say we buy a printing press and get down to business.

Coudln't we get existanai to write a spurious De Mons work?

He's nimble and fast, but if I aim well, I could probably fell him with a well-chosen tome, tie in front of a computer, and threaten with starvation and/or "damnation without relief", as Rowan Atkinson says. I have a feeling he works best confronted with deathlines. :)

#63

Like in that Poe story, everyone is mad--except the writer.

65LolaWalser

Wow, check this out Maki--French, but you get the idea (didn't look at the English page, often they ditch data)-scroll down to Oeuvres--says Nodier was one of the "most prolific French writers" and that the list is only a small part of his bibliography:

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Nodier

Maybe the translators don't know where to start.

I'm feeling veritable hunger pangs here: Description raisonnée d'une jolie collection de livres (Annotated description of a PRETTY collection of books!); Dictionnaire des onomatopées françaises (Dictionary of French onomatopoiea! How can I live without it!); Apothéoses et imprécations de Pythagore (Apotheoses and imprecations of Pythagoras!!!--that is, other people apotheosing or imprecating Pythagoras); Du langage factice appelé macaronique (On the artificial language called "macaronic") and on and on...

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Nodier

Maybe the translators don't know where to start.

I'm feeling veritable hunger pangs here: Description raisonnée d'une jolie collection de livres (Annotated description of a PRETTY collection of books!); Dictionnaire des onomatopées françaises (Dictionary of French onomatopoiea! How can I live without it!); Apothéoses et imprécations de Pythagore (Apotheoses and imprecations of Pythagoras!!!--that is, other people apotheosing or imprecating Pythagoras); Du langage factice appelé macaronique (On the artificial language called "macaronic") and on and on...

66Makifat

Dedalus translated Smarra and Trilby in a single edition, but beyond that, there is precious little.

http://www.librarything.com/work/1063560/workdetails/19131867

http://www.librarything.com/work/1063560/workdetails/19131867

67PimPhilipse

Available on Gutenberg:

Smarra ou les démons de la nuit Songes romantiques

Infernaliana - Anecdotes, petits romans, nouvelles et contes sur les revenans, les spectres, les démons et les vampires

(group read, anyone?)

Available on gallica.bnf.fr:

Apothéoses et imprécations / de Pythagore

Du langage factice appelé macaronique

Dictionnaire raisonné des onomatopées françaises

(and probably more, but the gallica site went down after a while)

Smarra ou les démons de la nuit Songes romantiques

Infernaliana - Anecdotes, petits romans, nouvelles et contes sur les revenans, les spectres, les démons et les vampires

(group read, anyone?)

Available on gallica.bnf.fr:

Apothéoses et imprécations / de Pythagore

Du langage factice appelé macaronique

Dictionnaire raisonné des onomatopées françaises

(and probably more, but the gallica site went down after a while)

68LolaWalser

I read Infernaliana recently, off the computer, and it was very enjoyable. I hope Gallica comes up again, I wanted to copy Jean Sbogar, it's damn difficult to find in print! (I'm not considering those newfangled POD things...)

69pgmcc

#68 I know what you mean. We had enough of the POD-People in the 1950s.

70PimPhilipse

According to abebooks, the Librairie à la bonne occasion in Quebec is offering a copy of Jean Sbogar that was printed in 1980 for Éditions France Empire.

71LolaWalser

#69

You may laugh, but it's clear they WERE among us! Nothing else explains modernity!

#70

Yes, saw that: a paperback from the eighties, Couverture frottée et souillée. Bah! For twenty two dollars I can buy twenty two one-dollar books!

I'm looking at the edition from 1938, though. However, i just placed some orders I shouldn't have so it will all have to wait.

You may laugh, but it's clear they WERE among us! Nothing else explains modernity!

#70

Yes, saw that: a paperback from the eighties, Couverture frottée et souillée. Bah! For twenty two dollars I can buy twenty two one-dollar books!

I'm looking at the edition from 1938, though. However, i just placed some orders I shouldn't have so it will all have to wait.

72LolaWalser

**

** **

** **

**

Man in the Holocene, Max Frisch

An old man retired to a Swiss village begins a descent into death and oblivion as incessant rains and thunderstorms seem to herald a general transformation of the landscape. In Geiser's last days the human is miniaturised until it practically disappears, as his mind increasingly falters and leaves the personal behind, and his attention becomes wholly consumed by the gigantic geological past of the planet and his canton. Very good.

Time's arrow, time's cycle, Stephen Jay Gould

S. J., how we miss thee! Frisch's book made me yearn for more thinking on the grand scale, in millions of years, so I grabbed this exploration of the most famous metaphors for progress and change in science--one imposing the idea of linear irrevocable directionality, the other an eternal cycle. As it turns out, neither "model" fits the facts, and Gould explains--brilliantly, as usual--how the worldview clashes of their champions (Thomas Burnet, James Hutton, Charles Lyell) shaped inquiry into the age and nature of the world, geology and biology. Gould's starting point is the frontispiece to Burnet's "Telluris Theoria Sacra", showing Jesus straddling the phases of Earth's transformation, history beginning at his left foot, proceeding clockwise, ending at the right. Time's arrow is bent into a cycle, or, as Mark Twain said it best: "History doesn't repeat, but it rhymes."

Un philosophe sous les toits, Emile Souvestre.

Souvestre's futuristic The world as it shall be was infinitely more fun that this moralistic collection. Twelve sketches of poor and humble folk inspire lofty thoughts in the writer, along the lines of "theirs will be the reward of Heaven". Pie in the sky. Skip the philosopher and go for the prophet, say I.

For love of the Dark One: Songs of Mirabai, Mirabai

Sometime in the sixteenth century a high born Hindu lady fell in love with a god, Krishna, dropped everything, family, friends, widow's weeds, and went through the land singing about it. The ecstasy is similar to the Sufi effusions, but--at least according to this translation--rather more starkly sexual. This truly is "body & soul" devotion. The singing was apparently literal, and although I suppose Mirabai's own melodies are lost or transformed after all this time, her texts are still sung and recorded. To look up: Lakshmi Shankar Sings Mira Bhajans; Les heures et les saisons: Lakshmi Shankar (HM); Chants of devotion. Lakshmi Shankar (Astree Auvidis); Mira Bhajans Sung by S. M. S. Subhalakshmi (EMI); Meera Bhajans. Kishori Amonkar (EMC); Anthologie de la musique de l'Inde vol. 2 (GREM)

74marietherese

I think that is my favourite Frisch. Of course, it may also be the first Frisch I read and the erste liebe thing may be colouring my recollection.

I, too, miss Stephen Jay Gould. He had a truly broad mind and an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He was an inspiring thinker. There are too few like him left.

I, too, miss Stephen Jay Gould. He had a truly broad mind and an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He was an inspiring thinker. There are too few like him left.

75LolaWalser

There you go, that was my first Frisch too. And Gould was golden, faults and baseball and all.

Precious little German books! One produced in 1917 in Dachau, when Dachau was just the name of a pleasant little town. What would one give to have it had remain so?

**

** **

**

Der Löwe Alois und andere Geschichten (Lion Alois and other stories) by Gustav Meyrink

In the first of these delicious comic stories, a little orphaned lion cub is raised by sheep and thinks he's one too. I totally LOL'd at his encounter with an older lion who couldn't believe his eyes when grass-grazing Alois started baa-ing at him. The animals speak Viennese, which is all the more hilarious. Another story expands on a tale of a murderer (from The Golem) who ends up as a mild-mannered gardener in a nunnery; there's a report from the Otherworld, run just as burocratically as This World; and another modern fable, of a high-thinking Oriental sage (a camel), eventually coming to a dire end when his Western pals lose ideals to hunger.

Die chinesische Mauer (The Chinese Wall) by Karl Kraus

This essay, which Kraus often read in public, was inspired by the anti-Chinese hysteria following the 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel. A young Christian woman was killed by a Chinese man she loved (but maybe not loved exclusively). The sensational topic finds matching lurid expression in Kraus' shrill, biting tones, resulting in a book that seems to hop and boil in one's hands. (My edition reproduces Oskar Kokoschka's graphics from the original--this was the only book by Kraus ever originally published illustrated.) Rarely are anti-racist and anti-clerical sentiments married to misogyny with such éclat.

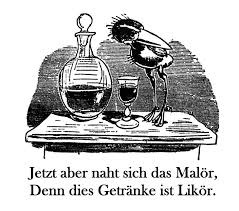

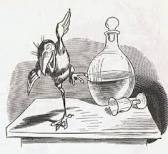

Brevier by Wilhelm Busch

The terrors Max and Moritz, the raven Hans Huckebein, a piano virtuoso wildly music-making and other versified comic strips. What can I do, Busch makes me laugh.

Hans eyeing the booze:

Hans dancing after imbibing booze:

Precious little German books! One produced in 1917 in Dachau, when Dachau was just the name of a pleasant little town. What would one give to have it had remain so?

**

** **

**

Der Löwe Alois und andere Geschichten (Lion Alois and other stories) by Gustav Meyrink

In the first of these delicious comic stories, a little orphaned lion cub is raised by sheep and thinks he's one too. I totally LOL'd at his encounter with an older lion who couldn't believe his eyes when grass-grazing Alois started baa-ing at him. The animals speak Viennese, which is all the more hilarious. Another story expands on a tale of a murderer (from The Golem) who ends up as a mild-mannered gardener in a nunnery; there's a report from the Otherworld, run just as burocratically as This World; and another modern fable, of a high-thinking Oriental sage (a camel), eventually coming to a dire end when his Western pals lose ideals to hunger.

Die chinesische Mauer (The Chinese Wall) by Karl Kraus

This essay, which Kraus often read in public, was inspired by the anti-Chinese hysteria following the 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel. A young Christian woman was killed by a Chinese man she loved (but maybe not loved exclusively). The sensational topic finds matching lurid expression in Kraus' shrill, biting tones, resulting in a book that seems to hop and boil in one's hands. (My edition reproduces Oskar Kokoschka's graphics from the original--this was the only book by Kraus ever originally published illustrated.) Rarely are anti-racist and anti-clerical sentiments married to misogyny with such éclat.

Brevier by Wilhelm Busch

The terrors Max and Moritz, the raven Hans Huckebein, a piano virtuoso wildly music-making and other versified comic strips. What can I do, Busch makes me laugh.

Hans eyeing the booze:

Hans dancing after imbibing booze:

76Existanai

Hans Huckebein - text with illustrations and a translation.

77Existanai

>that was my first Frisch too.

It's been a while since I read it, but Homo Faber is worth checking out, though I recall having some reservations. I believe you already have a copy, so I'd be interested in your opinion.

It's been a while since I read it, but Homo Faber is worth checking out, though I recall having some reservations. I believe you already have a copy, so I'd be interested in your opinion.

78LolaWalser

A couple months, and I'm already hopelessly behind both the reading and the remembering!

**

**

Eustace Chisholm and the works, and Malcolm, both by James Purdy

I mark the encounter with James Purdy with a white stone. Eustace Chisholm... is rather tragic; Malcolm rather comic; the former's humour grotesque, the latter's farcical and fantastical, but in both books the centre of everyone's action and reflection, is a beautiful teenage boy. He is the love and his is the love that cannot be had. Purdy's language is anti-realist, poetry potent, casting the shadow of another world and heightened moods over the grubby lives of his bohemian, dirt-poor characters.

**

**  **

**

Le diable amoureux (The devil in love) begins sweet, ends pear-shaped. Foolish young man invokes Beelzebub, demands service, gets it--and far more than he bargained, as the devil's female incarnation falls in love with him. Young man at first fears his unusual maid, then is persuaded that she's an ordinary human being and agrees to marry her, at which point for unclear reasons the devil reappears and terrifies the pants off the hapless dupe. Maybe the devil-maid can't take the church ceremony, or maybe Cazotte ran out of steam. I wished for more adventures, but had lots of drawings to look at instead (see samples in the Praising Real Books thread #2).

Imaginación y Fantasía: Cuentos de las Américas, Various

Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), Horacio Quiroga

The first is a short anthology with bite-size stories by Borges, Amado Nervo, Clemente Palma et al.; the Quiroga story inspired me to read the other book, with some of his best known tales. Lots of fantasy, some detective tales, some fancy levity (in one, a man becomes as light as a balloon, begins to bounce off surfaces, eventually floats off into the skies). Except for a few lighter stories he wrote for children (with animal protagonists, in one a giant anaconda, in another a riverful of rays and a forestful of tigers--both stories feature conflict and death, though), Quiroga is reliably depressed, grim and terrifying.

**

**

Eustace Chisholm and the works, and Malcolm, both by James Purdy

I mark the encounter with James Purdy with a white stone. Eustace Chisholm... is rather tragic; Malcolm rather comic; the former's humour grotesque, the latter's farcical and fantastical, but in both books the centre of everyone's action and reflection, is a beautiful teenage boy. He is the love and his is the love that cannot be had. Purdy's language is anti-realist, poetry potent, casting the shadow of another world and heightened moods over the grubby lives of his bohemian, dirt-poor characters.

**

**  **

**

Le diable amoureux (The devil in love) begins sweet, ends pear-shaped. Foolish young man invokes Beelzebub, demands service, gets it--and far more than he bargained, as the devil's female incarnation falls in love with him. Young man at first fears his unusual maid, then is persuaded that she's an ordinary human being and agrees to marry her, at which point for unclear reasons the devil reappears and terrifies the pants off the hapless dupe. Maybe the devil-maid can't take the church ceremony, or maybe Cazotte ran out of steam. I wished for more adventures, but had lots of drawings to look at instead (see samples in the Praising Real Books thread #2).

Imaginación y Fantasía: Cuentos de las Américas, Various

Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), Horacio Quiroga

The first is a short anthology with bite-size stories by Borges, Amado Nervo, Clemente Palma et al.; the Quiroga story inspired me to read the other book, with some of his best known tales. Lots of fantasy, some detective tales, some fancy levity (in one, a man becomes as light as a balloon, begins to bounce off surfaces, eventually floats off into the skies). Except for a few lighter stories he wrote for children (with animal protagonists, in one a giant anaconda, in another a riverful of rays and a forestful of tigers--both stories feature conflict and death, though), Quiroga is reliably depressed, grim and terrifying.

79SilentInAWay

Which story in the anthology was it that inspired you to read the Quiroga collection?

80LolaWalser

El hombre muerto, linked for you acá!

Although no doubt you already read it, analysed it, published a paper or four...

Although no doubt you already read it, analysed it, published a paper or four...

81marietherese

I love Quiroga! It must be that grim and depressing thing that makes me enjoy his work so very much (plus, it's just so incredibly vivid, visceral). I tried translating some Quiroga as a teen-it was a humiliating exercise. Absolute, abject failure. It did result in me realizing how remarkably difficult the translator's art is though (and that I wasn't the least suited to it).

82LolaWalser

Oh yes, vivid, visceral... Words like torn from the flesh, no? I imagine him grinding his teeth all the time.

**

**

Two great books by Leo Perutz. In From nine to nine we follow a furious young man with alarmingly peculiar behaviour dashing through Vienna on some mysterious errand. One accidental meeting after another illustrates that he is in a strange predicament, panic rising as some deadline looms. It is comic, it is absurd and then terrifying. I'm loath to spoil the delight of any detail, so just a little hint meant to bait bibliomaniacs--as in The Master of the Day of Judgment, there is a fatal book...

St. Peter's snow is a "bigger" book (though hardly longer). There is a Borgesian timelessness to most of Perutz I've read (or vice versa?), a universal, alchemical point of view which aligns different periods like so many pieces of lamb on a skewer. Here it acquires a blatant political dimension (the year is 1933...) Amberg, an aimless young doctor, pressed into the profession out of economic pragmatism, and half-absent from himself due to a unrequited, never confessed passion for another student, gets a job with a baron von Malchin in the latter's mist-enveloped domain. Even before he reaches the post there are portents which begin to wind his psyche--he sees the girl he's in love with in the small town closest to the village, and when it turns out that she is von Malchin's scientific collaborator, he almost expects it. The dream logic begins to overtake him--or maybe the reality IS this nightmarish? The baron's project is, first, to bring back religious faith to people--through a drug distilled from a wheat mould, or fungus, known as "St. Peter's snow". In the next step, the Holy Roman Empire is to be restored, complete with a legitimate Kaiser, a descendant of the Staufers (or Hohenstaufens) the baron tracked down in a poor Italian family. And then... Something goes wrong. COMPLETELY wrong.

Let's just say the Nazis didn't care one bit for Perutz's prognosis for their imperial dreams.

**

**

Two great books by Leo Perutz. In From nine to nine we follow a furious young man with alarmingly peculiar behaviour dashing through Vienna on some mysterious errand. One accidental meeting after another illustrates that he is in a strange predicament, panic rising as some deadline looms. It is comic, it is absurd and then terrifying. I'm loath to spoil the delight of any detail, so just a little hint meant to bait bibliomaniacs--as in The Master of the Day of Judgment, there is a fatal book...

St. Peter's snow is a "bigger" book (though hardly longer). There is a Borgesian timelessness to most of Perutz I've read (or vice versa?), a universal, alchemical point of view which aligns different periods like so many pieces of lamb on a skewer. Here it acquires a blatant political dimension (the year is 1933...) Amberg, an aimless young doctor, pressed into the profession out of economic pragmatism, and half-absent from himself due to a unrequited, never confessed passion for another student, gets a job with a baron von Malchin in the latter's mist-enveloped domain. Even before he reaches the post there are portents which begin to wind his psyche--he sees the girl he's in love with in the small town closest to the village, and when it turns out that she is von Malchin's scientific collaborator, he almost expects it. The dream logic begins to overtake him--or maybe the reality IS this nightmarish? The baron's project is, first, to bring back religious faith to people--through a drug distilled from a wheat mould, or fungus, known as "St. Peter's snow". In the next step, the Holy Roman Empire is to be restored, complete with a legitimate Kaiser, a descendant of the Staufers (or Hohenstaufens) the baron tracked down in a poor Italian family. And then... Something goes wrong. COMPLETELY wrong.

Let's just say the Nazis didn't care one bit for Perutz's prognosis for their imperial dreams.

83Makifat

Thanks for this!

I HAVE to get more Perutz! He is a neglected genius, at least in the English speaking world. He ought to be as well known as Borges...

I HAVE to get more Perutz! He is a neglected genius, at least in the English speaking world. He ought to be as well known as Borges...

85LolaWalser

Yes--I just did a quick search (what's the point when I only have the time for a "quick search" but not to read?)--Borges KNEW Perutz's stuff (and apparently Hitchcock mined Perutz for some of his twists, is that a spoiler?)

I bought The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters "because it was there" for a buck. I have no special interest in the sisters or their milieu; the only books BY them I've read so far are Nancy Mitford's charming, highly enjoyable The Sun King and Madame de Pompadour. Other than that, the merest fact of their existence, and the notorious information that politically they ran the gamut from Nazism to Communism, all I know about them was gleaned from this book. I don't know whether I'd feel more or less charitable if I had deeper insight. So, based on this edition by Charlotte Mosley (daughter-in-law of Diana, wife to Oswald, head of British Union of Fascists), my one dominant feeling is deepest loathing for the English upper classes, the dungheap that bred and breeds these specimens. Jessica Mitford (the "Communist") strikes me as the only decent person of the bunch, that is, the only one who wouldn't look down upon one not of her set, or kill one like a cockroach. The only one who doesn't in SOME FORM deny the humanity and dignity of other classes of people, which her sisters do constantly.

Unsurprisingly perhaps but still shockingly so, they are casually antisemitic, xenophobic and deeply racist. The letters concerning Jessica's daughter's "black" baby are disgusting, gloating and offended (serve her right and how could she do this to us) and the only unguarded moments in the book, although Nancy Mitford, the one with the loudest arrogance, lets loose with "wretched little yellow people" on the subject of the Vietnamese etc. I don't know how much is due to the editing, but the overall impression is of disingenuousness, insincerity and constant affectation--I realise that lots of it is congenital, but some is no doubt deliberate, especially as it begins to be clear that the correspondence won't remain private forever.

Ironically, it would be easier to forgive them if the example of Jessica didn't point out that one needn't be a slave to one's upbringing, that we have the capability to change, develop and become better. (In this connexion, I don't give a damn about judging people by the standards of their time. As long as ONE person transcended these standards, they are NOT inexorable.)

The reason this infuriates me so is that it is precisely in those attitudes that I see the germ of fascism and all warfare, be it military or social. Aristocracy is based on believing the ruled are vermin, essentially different from the elite, and adherence to wars springs from conviction that the enemy is vermin, essentially different from us.

Vive la guillotine.

I bought The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters "because it was there" for a buck. I have no special interest in the sisters or their milieu; the only books BY them I've read so far are Nancy Mitford's charming, highly enjoyable The Sun King and Madame de Pompadour. Other than that, the merest fact of their existence, and the notorious information that politically they ran the gamut from Nazism to Communism, all I know about them was gleaned from this book. I don't know whether I'd feel more or less charitable if I had deeper insight. So, based on this edition by Charlotte Mosley (daughter-in-law of Diana, wife to Oswald, head of British Union of Fascists), my one dominant feeling is deepest loathing for the English upper classes, the dungheap that bred and breeds these specimens. Jessica Mitford (the "Communist") strikes me as the only decent person of the bunch, that is, the only one who wouldn't look down upon one not of her set, or kill one like a cockroach. The only one who doesn't in SOME FORM deny the humanity and dignity of other classes of people, which her sisters do constantly.

Unsurprisingly perhaps but still shockingly so, they are casually antisemitic, xenophobic and deeply racist. The letters concerning Jessica's daughter's "black" baby are disgusting, gloating and offended (serve her right and how could she do this to us) and the only unguarded moments in the book, although Nancy Mitford, the one with the loudest arrogance, lets loose with "wretched little yellow people" on the subject of the Vietnamese etc. I don't know how much is due to the editing, but the overall impression is of disingenuousness, insincerity and constant affectation--I realise that lots of it is congenital, but some is no doubt deliberate, especially as it begins to be clear that the correspondence won't remain private forever.

Ironically, it would be easier to forgive them if the example of Jessica didn't point out that one needn't be a slave to one's upbringing, that we have the capability to change, develop and become better. (In this connexion, I don't give a damn about judging people by the standards of their time. As long as ONE person transcended these standards, they are NOT inexorable.)

The reason this infuriates me so is that it is precisely in those attitudes that I see the germ of fascism and all warfare, be it military or social. Aristocracy is based on believing the ruled are vermin, essentially different from the elite, and adherence to wars springs from conviction that the enemy is vermin, essentially different from us.

Vive la guillotine.

86varielle

Perutz's The Marquis of Bolibar ranks in my personal top ten best books ever.

87Mr.Durick

Lola, I just scanned the reviews already posted for The Mitfords: Letters... and think you should copy your message 85 there as a counterweight.

Robert

Robert

88tomcatMurr

I also enjoyed Mitford's book on Pompadour, a felicitous match of biographer and subject, I thought. Beyond that, I never saw much point in the Mitfords. Or the Sitwells, for that matter.

I must try to get hold of some Perutz.

I must try to get hold of some Perutz.

89LolaWalser

#86

I love it too!

#87

It could be a matter of emphasis... I don't think anyone can miss the ugliness, it's just that they prefer to like, or at least admire, these remarkable, smart, stylish women. I should add that the letters weren't nearly as interesting as I expected, in historical or literary terms (this edition at least).

#89

The Sun King is even better. Nancy Mitford seems to have fancied herself as a French aristocrat, pre-1789 (the sisters refer to her as "the French lady"). Total immersion.

I love it too!

#87

It could be a matter of emphasis... I don't think anyone can miss the ugliness, it's just that they prefer to like, or at least admire, these remarkable, smart, stylish women. I should add that the letters weren't nearly as interesting as I expected, in historical or literary terms (this edition at least).

#89

The Sun King is even better. Nancy Mitford seems to have fancied herself as a French aristocrat, pre-1789 (the sisters refer to her as "the French lady"). Total immersion.

90LolaWalser

On, on and awwwaaaayy...

Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy

Continuing with the Mitfords currently in my library. In 1956 or thereabouts Nancy Mitford published an article on English aristocracy and for SOME reason it created quite a brouhaha, eliciting responses from, among others, Evelyn Waugh, Christopher Sykes, John Betjeman (a silly poem)--the lot was published together in a book, along with one Mr. Ross' article on the defining traits of the U and non-U speech: "U" standing in for "upper class".

It's almost sixty years later, I am not English, never suffered class discrimination, and possibly "therefore" I can't see what was so inflammatory about Mitford's article. In the letters, the sisters are annoyed by it; the odious Evelyn Waugh smacks her down as a "Socialist" (funny that)--my one guess is that merely saying out loud what everyone knew, i.e. that the "U"s say and do things differently from the "non-U"s was scandalous. Nancy DID have a penchant for saying all kinds of things out loud, as I noted before.

**

**