Russell A. PotterInterview

Auteur de Pyg: The Memoirs of Toby, the Learned Pig

Interview de l'auteur

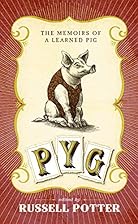

Russell A. Potter is a Professor of English at Rhode Island College (and an active LibraryThing member). He is the author of Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875 and Spectacular Vernaculars: Hip-Hop and the Politics of Postmodernism. His first novel, PYG: The Memoirs of Toby, a Learned Pig, was published in the UK by Canongate and will be released in the US and Canada by Penguin at the end of July.

Russell A. Potter is a Professor of English at Rhode Island College (and an active LibraryThing member). He is the author of Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875 and Spectacular Vernaculars: Hip-Hop and the Politics of Postmodernism. His first novel, PYG: The Memoirs of Toby, a Learned Pig, was published in the UK by Canongate and will be released in the US and Canada by Penguin at the end of July.

Where did you get the idea for PYG? Can you tell us a bit about the historical precedents for Toby?

I first read about the "Learned pig"—an act in which the animal spelled out answers to audience questions using pasteboard cards—many years ago in the pages of Richard Altick's magisterial volume The Shows of London. Some time later, perusing Ricky Jay's delightful compendium of curiosities, Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women, I was surprised to discover how many such pigs there had been in the 1780s, with several living claimants vying for attention with automaton versions of the same act. Jay also mentioned that the proprietor of one of these pigs had gone so far as to issue an "autobiography" of Toby—for so all pigs seemed to be named—which gave a punning account of his "life and opinions." It occurred to me then that, should there be a pig who had learned not only his letters, but gained through them the ability to express his own feelings, how much richer and more varied a tale might be told from his viewpoint as an animal exhibited as a "Freak of Nature," and so PYG was born.

The book is beautifully designed; what was the process like for choosing the images, font and other elements of the text?

I love the design as well, though in part it was simply the result of a series of fortuitous accidents. I'd always conceived of it as a book which would emulate in its form the conventions of a late-18th century novel, and when the designer at Canongate suggested Caslon Antique I was delighted. Originally, I'd wanted to use the same woodcut of a learned pig that appeared in Ricky Jay's book, but since that volume was about to be republished, Jay asked us to not to copy that design. I set out to locate an image from the period, and in the wonderful Osborn collection of early children's books at the Toronto Public Library, I found the Darton volume with the image of a learned pig. I'd already given all the chapters three-letter names, so it seemed natural to use this image and have the titles spelled out with the cards—I made a rough mockup in Photoshop and sent it to the designer, who did the rest.

The research process for "Pyg" must have been great fun! What were some of the sources you used, and what did you learn that surprised you?

The research process for "Pyg" must have been great fun! What were some of the sources you used, and what did you learn that surprised you?

I've mentioned Altick and Jay, but of course the internet today offers a seemingly limitless array of historical texts and images. Among the best sources were British History Online, which has scanned in all the county histories of England, Scotland, and Wales—here one could find a description of almost any town or village, its prominent buildings, inns, churches, and so forth—as well as OldHistoricalMaps.co.uk, which had essential maps showing the state of the roads in the 1780s. Lastly, in order to make sure that the language of the tale was not, in any avoidable way, anachronistic, I made use of the OED and Google's wonderful nGram database. The most surprising discovery I made there was that "oink" turned out to be an American coinage of early 20th-century vintage, and I was thus obliged to use "squeal" and "grunt" instead!

For readers of PYG who might want to delve deeper into 18th-century culture, do you have some particularly good books that you'd recommend (reference sources or books from the period)?

One of the things about the 18th century is its incredibly rich visual and textual culture. One of my first jobs out of college was working at a microfilm company which had set out, in a much the way that Google Books would later, to film every book in English listed in the ESTC (Eighteenth-century Short Title Catalogue). My job title was actually "Editor of the 18th Century"! And we really did film everything: handbills, broadsides, funeral tickets, bills for the enclosures of lands, sermons, and even the odd novel. In some ways, I still think this the best way to get a feel for a period: scour its ephemera, soak oneself its most ubiquitous and random leavings, and then it really gets under your skin. I'd also recommend books which survey the period's visual and material culture; in addition to Altick's The Shows of London there's David Coke and Alan Borg's brilliant new Vauxhall Gardens: A History, where—although, alas, a learned pig did not appear—all manner of curious entertainments, from fortune-telling hermits to King Edward's Crown done up in lights could be seen; their book is a veritable garden of delights in itself.

Tell us about Toby's social media presence: where can readers go to keep tabs on him?

My main online presence is at my blog, but I also have a Twitter feed, @tobythepig, and a tumblr blog where I post some pig-related visual imagery.

When and where do you do most of your writing? Do you compose longhand, or on the computer?

Oddly enough for someone obsessed with the materiality of the past, I rarely make use of pen and paper; I've done all my writing, academic and fictional, on computers, starting with an old Kaypo II that I bought back in 1983. It's really liberated me to concentrate on the "voice" in writing, with the knowledge that everything I do is instantaneously revisable, discardable, or—if it passes eventual muster—saveable.

What's your own library like today? What sorts of books would we find on your shelves?

Most of my collection is online at LibraryThing (here), so interested parties can have a virtual "browse" of my shelves any time they like. I have a few books from each century—including a little duodecimo edition of Johnson's Rasselas just that the one Toby has in the novel—and collect mainly literary fiction by my favorite authors, particularly Ursula K. LeGuin and Steven Millhauser. In my non-fiction incarnation, I've worked extensively on the history of Arctic exploration, and so that makes up the biggest single section of my collection. Among my most prized volumes is an 1820 edition of Sir William Edward Parry's account of his first Arctic expedition, printed in Philadelphia by Abraham Small, one of the earliest US editions of a work of polar exploration.

What have you read and enjoyed recently?

Aside from the books I'm currently teaching, I've been on a graphic novel jag of sorts—I especially enjoyed Derf's My Friend Dahmer and am just starting Harvey Pekar's Cleveland (I'm originally from Cleveland, and have a sense of personal connection with both these writers). I'm also just starting on Quotidiana, a collection of elegant essays by Patrick Madden, whom I met a couple of weeks ago at the Ocean State Writing Conference.

Do you have any idea yet of your next project?

As it happens, the novel I completed just before PYG may end up being my "next" project—its main character, a Victorian panoramist, is another of the school of "old showmen" who criss-crossed Britain, offering their diversions at county fairs and lyceum halls. I'm also at work on a new project, a somewhat more fantastical narrative, aimed at younger readers, whose main character is the granddaughter of a well-known Egyptologist who discovers in her grandfather's house signs that her family connection to the gods of Dynastic times may be far more direct and personal than she could possibly have imagined. If PYG does well, I hope very much that both these novels will soon see the light of day.

—interview by Jeremy Dibbell