thorold lives in a society of emitters in Q2 2022

Ce sujet est poursuivi sur thorold is cast by Fortune on a frowning coast in Q3 2022.

DiscussionsClub Read 2022

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

1thorold

Je vis dans une société d'émetteurs (en étant un moi-même) : chaque personne que je rencontre ou qui m'écrit, m'adresse un livre, un texte, un bilan, un prospectus, une protestation, une invitation à un spectacle, à une exposition, etc. La jouissance d'écrire, de produire, presse de toutes parts...

—Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes (1975) p.96

Rough translation: "I live in a society of emitters {senders, broadcasters?} (whilst being one myself): each person I meet or who writes to me, sends me a book, a text, a report, a prospectus, a protest, an invitation to a show, an exhibition, etc. The pleasure of writing, of producing, presses from all sides..."

That was written a quarter of a century before the age of social media.

3thorold

Q1 Reading stats:

I finished 41 books in Q1 (Q4: 47).

Author gender: F: 7, M: 33, other: 1 (70% M) (Q4: 68% M)

Language: EN 22, NL 6, DE 6, FR 6, ES 1 (47% EN) (Q4 57% EN)

Translations: 1 from Polish

8 books were related to the Q1 "Indian Ocean" theme

Publication dates from 1850 to 2022, mean 1981, median 1997; 6 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 31, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 2, audiobooks 0, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 3 — 66% from the TBR (Q4: 17% from the TBR)

36 unique first authors (1.3 books/author; Q4 1.3)

By gender: M 28, F 7, Other 1 : 78% M (Q4 78% M)

By main country: UK 10, NL 7, FR 4, DE 4, US 4, and various singletons

TBR pile evolution:

01/01/2022: 93 books (77389 book-days) (change: 8 read, 12 added)

01/04/2022: 84 books (77762 book-days) (change: 31 read, 22 added)

A good bit of TBR pile churn going on in the last months, but I seem to have been reading mostly from the top again, so the average days per book has gone up from 832 to 926. That's obviously related to the lockdown period when I stopped going to the library again, but I should try to read one or two more from the long-stay end. The oldest on the pile are two books from June 2011, then there's one from 2012 and one from 2014.

I finished 41 books in Q1 (Q4: 47).

Author gender: F: 7, M: 33, other: 1 (70% M) (Q4: 68% M)

Language: EN 22, NL 6, DE 6, FR 6, ES 1 (47% EN) (Q4 57% EN)

Translations: 1 from Polish

8 books were related to the Q1 "Indian Ocean" theme

Publication dates from 1850 to 2022, mean 1981, median 1997; 6 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 31, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 2, audiobooks 0, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 3 — 66% from the TBR (Q4: 17% from the TBR)

36 unique first authors (1.3 books/author; Q4 1.3)

By gender: M 28, F 7, Other 1 : 78% M (Q4 78% M)

By main country: UK 10, NL 7, FR 4, DE 4, US 4, and various singletons

TBR pile evolution:

01/01/2022: 93 books (77389 book-days) (change: 8 read, 12 added)

01/04/2022: 84 books (77762 book-days) (change: 31 read, 22 added)

A good bit of TBR pile churn going on in the last months, but I seem to have been reading mostly from the top again, so the average days per book has gone up from 832 to 926. That's obviously related to the lockdown period when I stopped going to the library again, but I should try to read one or two more from the long-stay end. The oldest on the pile are two books from June 2011, then there's one from 2012 and one from 2014.

4thorold

Highlights of Q1

— The books of Jacob — a fabulously complicated historical novel about a subject completely new to me.

— catching up with Abdulrazak Gurnah for the Indian Ocean thread

— re-reading David Copperfield at last

— Footsteps : adventures of a romantic biographer — I must read more Richard Holmes

— getting to read Patrick Gale's new novel Mother's boy (and revisiting its subject, Charles Causley)

— discovering Henry de Monfreid

— Jan Swafford's Brahms biography

— and of course reading my first home-made hardback!

Q2 Goals

— attack the old end of the TBR (no, really, this time I mean it...)

— read Ali Smith's new book, when it arrives

— the RG "Outcasts and Castaways" theme read

— Wilkie Collins and Mrs Gaskell for the Victorian thread: I've already started The law and the lady

— all the other Q1 goals I forgot about

— I'm also hoping to travel a bit, with three short trips lined up before the end of June: fingers crossed that they can go ahead...

— The books of Jacob — a fabulously complicated historical novel about a subject completely new to me.

— catching up with Abdulrazak Gurnah for the Indian Ocean thread

— re-reading David Copperfield at last

— Footsteps : adventures of a romantic biographer — I must read more Richard Holmes

— getting to read Patrick Gale's new novel Mother's boy (and revisiting its subject, Charles Causley)

— discovering Henry de Monfreid

— Jan Swafford's Brahms biography

— and of course reading my first home-made hardback!

Q2 Goals

— attack the old end of the TBR (no, really, this time I mean it...)

— read Ali Smith's new book, when it arrives

— the RG "Outcasts and Castaways" theme read

— Wilkie Collins and Mrs Gaskell for the Victorian thread: I've already started The law and the lady

— all the other Q1 goals I forgot about

— I'm also hoping to travel a bit, with three short trips lined up before the end of June: fingers crossed that they can go ahead...

5thorold

First book of Q2 — this is one that's been on the TBR since 2017 when I had a little diversion into reading Mythologies and Le plaisir du texte.

Roland Barthes, par Roland Barthes (1975) by Roland Barthes (France, 1915-1980)

Well, it wouldn't be a dull, conventional memoir, would it? Writing about himself, Barthes limits the hard biographical facts to a few briefly annotated family photos from his childhood in Bayonne and a two-page CV, and in between them he gives us a couple of hundred index-card sized fragments talking about his "real" life, which of course revolves around ideas and writings rather than boring things like dates, places and people. None of the fragments is much more than a paragraph or two long, with the only slightly longer pieces being a catalogue of books he might have written but didn't, and a discussion (you can see where this is going...) of the pleasures of the very short form.

In between times, we get cartoons, photos, sample exam questions, and a couple of examples of Barthes's painting — my favourite was an abstract doodle in the middle of a sheet of Sorbonne notepaper, titled "Gaspillage" (wasting paper). As if that wasn't enough, we also get the sheet music for a song he composed — I haven't tried to play that. He was obviously the Richard Feynman of semiotics.

You probably need at least a little bit of tolerance for French semioticians to enjoy this, and it's obviously more of a bedside book to dip into than a book you should read in one go, but if you like that sort of thing...

Roland Barthes, par Roland Barthes (1975) by Roland Barthes (France, 1915-1980)

Well, it wouldn't be a dull, conventional memoir, would it? Writing about himself, Barthes limits the hard biographical facts to a few briefly annotated family photos from his childhood in Bayonne and a two-page CV, and in between them he gives us a couple of hundred index-card sized fragments talking about his "real" life, which of course revolves around ideas and writings rather than boring things like dates, places and people. None of the fragments is much more than a paragraph or two long, with the only slightly longer pieces being a catalogue of books he might have written but didn't, and a discussion (you can see where this is going...) of the pleasures of the very short form.

In between times, we get cartoons, photos, sample exam questions, and a couple of examples of Barthes's painting — my favourite was an abstract doodle in the middle of a sheet of Sorbonne notepaper, titled "Gaspillage" (wasting paper). As if that wasn't enough, we also get the sheet music for a song he composed — I haven't tried to play that. He was obviously the Richard Feynman of semiotics.

You probably need at least a little bit of tolerance for French semioticians to enjoy this, and it's obviously more of a bedside book to dip into than a book you should read in one go, but if you like that sort of thing...

6thorold

>4 thorold: Something to add to the aims for Q2: I see I’m creeping up on my 2000th LT review (>5 thorold: was no.1991). I managed to make The magic mountain review no.1000, so I need to do something a little bit special for 2000 as well. I was wondering about something related to what Victoria Wood used to call “the Minnellium” (see https://youtu.be/zk6kNA9zKzY).

Any suggestions, anybody? I’ve already done The discovery of heaven, The elementary particles and Stieg Larsson…

Any suggestions, anybody? I’ve already done The discovery of heaven, The elementary particles and Stieg Larsson…

7labfs39

>6 thorold: No suggestions yet, but interesting question. You made me curious as to how many reviews I have written and when I might be having a noteworthy milestone. Not for a while, next year...

8thorold

Meanwhile, I've been trying out a new strategy: instead of (or perhaps as well as...) talking about reading the oldest books on the TBR, I've actually read one of the two oldest. This one came back from the charity shop in June 2011, so it's been on the pile for just short of 4000 of those 78000 book-days I was talking about.

To give some sort of perspective, during the time I was letting this book ripen on the shelf, its author added four more parts to the series it comes from. The most recent of those is well over 800 pages thick, too...

De gevarendriehoek (1985) by A F Th van der Heijden (Netherlands, 1951- )

During the opening chapter of this second part of the "Tandeloze Tijd" sequence, we see perpetual student Albert holed up in his parents' home in Geldrop and at last preparing for his final exams. But it's a false dawn, unfortunately: A.F.Th. plays his Proustian joker and whisks Albert back to his earliest childhood memories, and it takes a good 450 pages to get him back to the point where we came in at the start of the previous volume. A small bonus is that we learn how some of the previously unexplained characters fit in, but I suspect most readers will by now be despairing of the Sisyphean task of attacking the remaining six parts of this autobiographical roman fleuve...

The "danger triangle" of the title defines the bounds of the Geldrop neighbourhood where Albert spent his early years, cut off from the rest of the world by a main road, a canal and a railway line. But it also refers to another kind of triangle that features in Albert's nightmares about his "sexual inadequacy", a problem he spends most of the second part of the book trying to rectify. It's difficult to say whether Albert's relationships with his various vulnerable girlfriends are more disturbing than the drunken violence and the hecatomb of domestic animals that between them dominate the first half of the book, though.

Strangely, despite the very unappealing characters and subject-matter, this is a book that does suck you in, and once I'd actually opened it I kept on reading with a kind of revolted fascination. Van der Heijden is a clever and vivid story-teller, and he knows what he's doing. Improbable as it all is, you feel as if you're getting a realistic picture of working-class life in the Eindhoven suburbs of the fifties and sixties.

To give some sort of perspective, during the time I was letting this book ripen on the shelf, its author added four more parts to the series it comes from. The most recent of those is well over 800 pages thick, too...

De gevarendriehoek (1985) by A F Th van der Heijden (Netherlands, 1951- )

During the opening chapter of this second part of the "Tandeloze Tijd" sequence, we see perpetual student Albert holed up in his parents' home in Geldrop and at last preparing for his final exams. But it's a false dawn, unfortunately: A.F.Th. plays his Proustian joker and whisks Albert back to his earliest childhood memories, and it takes a good 450 pages to get him back to the point where we came in at the start of the previous volume. A small bonus is that we learn how some of the previously unexplained characters fit in, but I suspect most readers will by now be despairing of the Sisyphean task of attacking the remaining six parts of this autobiographical roman fleuve...

The "danger triangle" of the title defines the bounds of the Geldrop neighbourhood where Albert spent his early years, cut off from the rest of the world by a main road, a canal and a railway line. But it also refers to another kind of triangle that features in Albert's nightmares about his "sexual inadequacy", a problem he spends most of the second part of the book trying to rectify. It's difficult to say whether Albert's relationships with his various vulnerable girlfriends are more disturbing than the drunken violence and the hecatomb of domestic animals that between them dominate the first half of the book, though.

Strangely, despite the very unappealing characters and subject-matter, this is a book that does suck you in, and once I'd actually opened it I kept on reading with a kind of revolted fascination. Van der Heijden is a clever and vivid story-teller, and he knows what he's doing. Improbable as it all is, you feel as if you're getting a realistic picture of working-class life in the Eindhoven suburbs of the fifties and sixties.

9thorold

This is a book I came across on archive.org a few years ago whilst browsing around for old yachting memoirs. A bit outside the scope of what I was looking for, but I downloaded it anyway.

I thought it might be fun to read it for the Victorian theme:

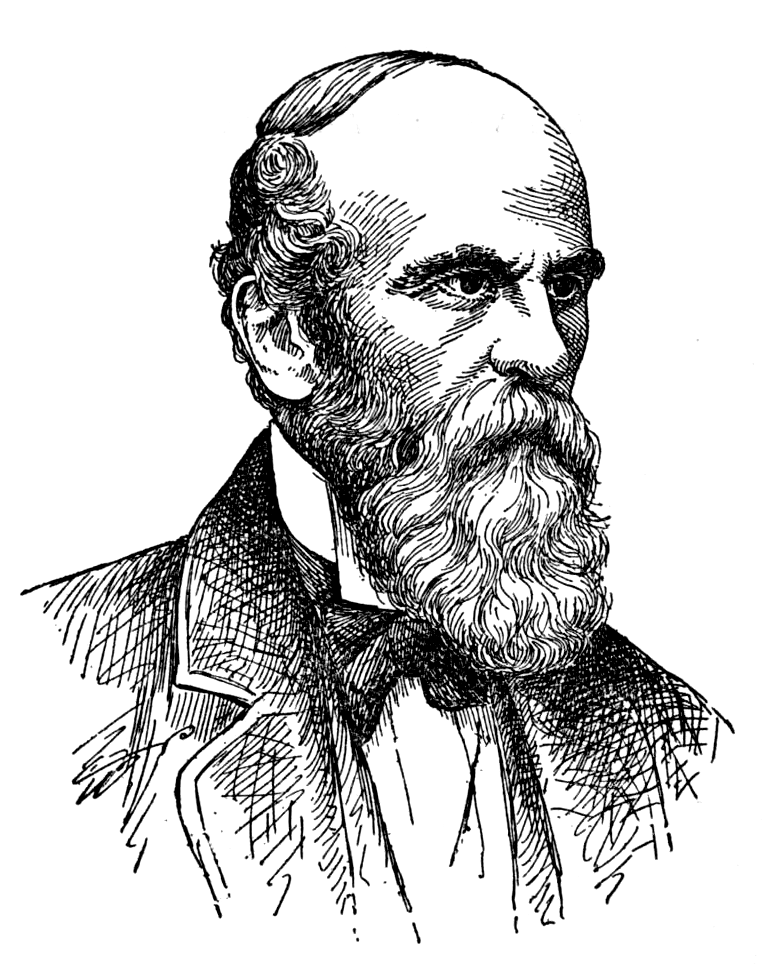

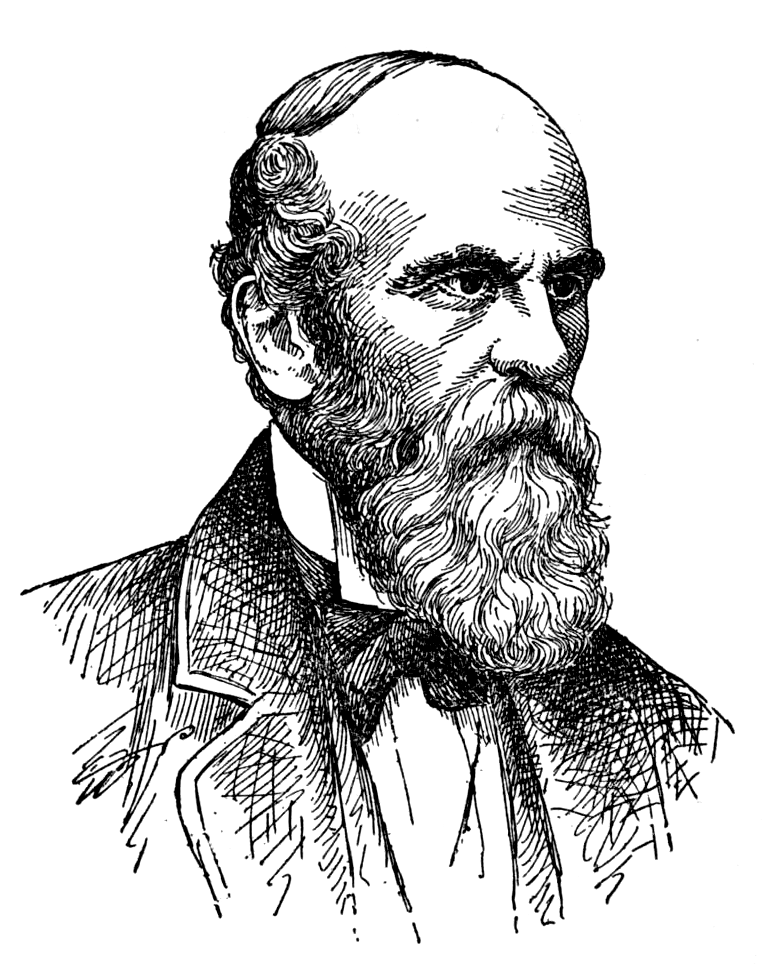

A yachting cruise in the Baltic (1863) by Samuel Robert Graves (UK, Ireland, 1818-1873)

Photo of Graves's statue in St George's Hall Liverpool by Mike Peel, via Wikipedia

In the 1860s the idea of low-budget cruising yachts accessible to ordinary middle-class people was still some way away (John MacGregor was just beginning to experiment with his one-person yawl Rob Roy), and "yachting" was reserved for the sort of people who run "superyachts" today. People like S R Graves, Irish-born Liverpool businessman and shipowner, Mayor of Liverpool, Commodore of Royal Mersey Yacht Club, chair of every conceivable committee concerned with the arts, sciences, economy or welfare, who would be elected MP for the city a couple of years after this book came out.

Graves was no rough-hewn shipowner in the Onedin Line tradition, but a classic Victorian polymath, interested in everything from palaeontology to public health, soaking up facts and figures the way modern travellers soak up sunshine and booze. He was clearly very proud of his Irish heritage, and often draws parallels from Irish history, whether or not they happen to be helpful. The book is absolutely groaning with data, with no fewer than four appendices containing detailed digests of the economies of the countries he visited. And in case you ever wanted to establish a Foundling Hospital, you will find enough information here to build your own and calculate the costs and mortality rates.

Graves's yacht, the patriotically named Ierne, was in the classic mode of the time, with a professional crew of about six, plus a steward and a Baltic pilot ("easily found for around 10 pounds a month"). If something interesting happened at a convenient time during the day, the Commodore and his travelling companion the Doctor might help the crew with sail-handling, but apart from that they seem to have spent their time at sea fishing, sketching, and investigating the life of the sea-bed with the help of a marine-biology trawl and a jar of spirits. But not on Sundays, of course: one of the few negative things Graves mentions about Ierne is how limited her "Sunday library" is. Once Divine Service is over, it's a dull day for them, sharing the couple of books of old sermons that are all she has on board in the way of non-secular reading-matter.

There's not much in the way of descriptions of sailing and navigation here, the book really comes alive when they get into port.

We hear about Copenhagen, Stockholm and Uppsala. In Stockholm, they bump into two honorary members of the Royal Mersey: Prince Oscar of Sweden, who arranges for them to see Drottningholm and some other royal residences, and Queen Victoria's 18-year-old son Prince Alfred, who is on an "informal" visit to the Baltic with about half the Royal Navy. Alfred urges them to come to come to St Petersburg with him, so they tag along with the fleet, giving Graves the excuse to bombard us with information about the Navy as it was in that awkward transitional stage, half still stuck in the Nelson era and half already playing with ironclad ships, steam propulsion and breech-loading guns.

We then get the full tour of St Petersburg in the days of Alexander II (Graves does not approve of Catherine the Great and her Hermitage full of atheistic Frenchmen), before Graves and the Doctor capriciously decide to hop on the recently-opened railway to Moscow, leaving the Ierne to make her own way to Göteborg and wait for them. Moscow — the first time I've read about it in a yachting book — gets a detailed inspection too, including the waterworks and numerous hospitals and churches. Then it's back to Sweden by steamer via Finland and through the Gotha Canal to meet the Ierne again for the trip home around Cape Wrath to the Mersey.

The Ierne (far right) off Waxholm with Prince Alfred's ship and its escort

I thought it might be fun to read it for the Victorian theme:

A yachting cruise in the Baltic (1863) by Samuel Robert Graves (UK, Ireland, 1818-1873)

Photo of Graves's statue in St George's Hall Liverpool by Mike Peel, via Wikipedia

In the 1860s the idea of low-budget cruising yachts accessible to ordinary middle-class people was still some way away (John MacGregor was just beginning to experiment with his one-person yawl Rob Roy), and "yachting" was reserved for the sort of people who run "superyachts" today. People like S R Graves, Irish-born Liverpool businessman and shipowner, Mayor of Liverpool, Commodore of Royal Mersey Yacht Club, chair of every conceivable committee concerned with the arts, sciences, economy or welfare, who would be elected MP for the city a couple of years after this book came out.

Graves was no rough-hewn shipowner in the Onedin Line tradition, but a classic Victorian polymath, interested in everything from palaeontology to public health, soaking up facts and figures the way modern travellers soak up sunshine and booze. He was clearly very proud of his Irish heritage, and often draws parallels from Irish history, whether or not they happen to be helpful. The book is absolutely groaning with data, with no fewer than four appendices containing detailed digests of the economies of the countries he visited. And in case you ever wanted to establish a Foundling Hospital, you will find enough information here to build your own and calculate the costs and mortality rates.

Graves's yacht, the patriotically named Ierne, was in the classic mode of the time, with a professional crew of about six, plus a steward and a Baltic pilot ("easily found for around 10 pounds a month"). If something interesting happened at a convenient time during the day, the Commodore and his travelling companion the Doctor might help the crew with sail-handling, but apart from that they seem to have spent their time at sea fishing, sketching, and investigating the life of the sea-bed with the help of a marine-biology trawl and a jar of spirits. But not on Sundays, of course: one of the few negative things Graves mentions about Ierne is how limited her "Sunday library" is. Once Divine Service is over, it's a dull day for them, sharing the couple of books of old sermons that are all she has on board in the way of non-secular reading-matter.

There's not much in the way of descriptions of sailing and navigation here, the book really comes alive when they get into port.

We hear about Copenhagen, Stockholm and Uppsala. In Stockholm, they bump into two honorary members of the Royal Mersey: Prince Oscar of Sweden, who arranges for them to see Drottningholm and some other royal residences, and Queen Victoria's 18-year-old son Prince Alfred, who is on an "informal" visit to the Baltic with about half the Royal Navy. Alfred urges them to come to come to St Petersburg with him, so they tag along with the fleet, giving Graves the excuse to bombard us with information about the Navy as it was in that awkward transitional stage, half still stuck in the Nelson era and half already playing with ironclad ships, steam propulsion and breech-loading guns.

We then get the full tour of St Petersburg in the days of Alexander II (Graves does not approve of Catherine the Great and her Hermitage full of atheistic Frenchmen), before Graves and the Doctor capriciously decide to hop on the recently-opened railway to Moscow, leaving the Ierne to make her own way to Göteborg and wait for them. Moscow — the first time I've read about it in a yachting book — gets a detailed inspection too, including the waterworks and numerous hospitals and churches. Then it's back to Sweden by steamer via Finland and through the Gotha Canal to meet the Ierne again for the trip home around Cape Wrath to the Mersey.

The Ierne (far right) off Waxholm with Prince Alfred's ship and its escort

10SassyLassy

>9 thorold: Fascinating, and also a reminder that I must read MacGregor's book, here somewhere.

11thorold

>10 SassyLassy: Oh, yes, you must! MacGregor is a true Victorian eccentric. E E Middleton, who sailed a MacGregor-designed boat round Britain (The cruise of the Kate), is even odder. Jonathan Raban sums him up delightfully as "a man whose head was peppered with stings from the swarm of bees that he kept in his bonnet".

----

Another book I'd set aside for the Indian Ocean. As I've said before, I've never quite made my mind up about Ondaatje, and this book left me as perplexed as ever.

Anil's ghost (2000) by Michael Ondaatje (Sri Lanka, Canada, 1943- )

Anil is a forensic pathologist, who returns to Sri Lanka, the country where she grew up, to take part in a UN investigation of human rights abuses during the recent (and still ongoing) civil wars. Together with archaeologist Sarath, his surgeon brother Gamini, and the artist Ananda, she pieces together the history of a recent skeleton that has anomalously turned up in an archaeological site from a much older period.

This is a book full of fascinating and often horrifying details about the consequences of communal violence, with some really beautiful writing that sticks in the mind, but it's also a very discursive kind of a book, constantly shying away from anything that looks like a neatly-resolved plot, something Ondaatje clearly felt would be inappropriate in this kind of context. As a result, there are all kinds of side-tracks that tell us fascinating things about the lives of forensic pathologists or plumbago miners, but don't necessarily deepen our understanding of the characters and their story. In a less-distinguished writer you'd call this "research dumping".

I think the focus on the technical aspects of what extreme violence does to human bodies works against the book as well: we end up with a striking, but very generic, picture of communal violence that doesn't have much to tie it to the specific Sri Lankan setting. Also, it gives a lot of weight to scientific details that Ondaatje isn't necessarily very competent to work with on his own: There were a couple of unimportant but conspicuous errors in technical terms that made it apparent that he hadn't run the final text past his expert advisors (e.g. "microtone" for "microtome", and "millimetres" for "millilitres" — those could have been dictation mistakes).

----

Another book I'd set aside for the Indian Ocean. As I've said before, I've never quite made my mind up about Ondaatje, and this book left me as perplexed as ever.

Anil's ghost (2000) by Michael Ondaatje (Sri Lanka, Canada, 1943- )

Anil is a forensic pathologist, who returns to Sri Lanka, the country where she grew up, to take part in a UN investigation of human rights abuses during the recent (and still ongoing) civil wars. Together with archaeologist Sarath, his surgeon brother Gamini, and the artist Ananda, she pieces together the history of a recent skeleton that has anomalously turned up in an archaeological site from a much older period.

This is a book full of fascinating and often horrifying details about the consequences of communal violence, with some really beautiful writing that sticks in the mind, but it's also a very discursive kind of a book, constantly shying away from anything that looks like a neatly-resolved plot, something Ondaatje clearly felt would be inappropriate in this kind of context. As a result, there are all kinds of side-tracks that tell us fascinating things about the lives of forensic pathologists or plumbago miners, but don't necessarily deepen our understanding of the characters and their story. In a less-distinguished writer you'd call this "research dumping".

I think the focus on the technical aspects of what extreme violence does to human bodies works against the book as well: we end up with a striking, but very generic, picture of communal violence that doesn't have much to tie it to the specific Sri Lankan setting. Also, it gives a lot of weight to scientific details that Ondaatje isn't necessarily very competent to work with on his own: There were a couple of unimportant but conspicuous errors in technical terms that made it apparent that he hadn't run the final text past his expert advisors (e.g. "microtone" for "microtome", and "millimetres" for "millilitres" — those could have been dictation mistakes).

12labfs39

>11 thorold: Although I haven't read it in a while, Anil's Ghost is a favorite. I found it less of a plot-driven book than a big-question book. Besides the obvious themes of identity and the effects of trauma, lies the question of truth and it's relationship to justice. At one point one of the characters says, I would tell the truth if I thought it would make any difference (paraphrased). In violent, chaotic times, does the truth matter? Does it effect anything? Is it worth it to suffer for the truth, if you know from the outset that it will not change anything? Does truth exist in a vacuum? I like thinking about these things, so this book resonated with me.

13thorold

>12 labfs39: Yes, that makes sense — there’s a kind of tension between the mechanical process of establishing truth from evidence and the human question of what you can do with that truth. I suppose that’s part of why it can feel like an unsatisfying book, because we’re conditioned to want stories where people discover truth and as a result they can all live happily ever after and marry the prince.

14SassyLassy

>11 thorold: "a man whose head was peppered with stings from the swarm of bees that he kept in his bonnet" I love that!

>11 thorold: >12 labfs39: Also a favourite book of mine for reasons you've both given. I'm not fond of happily ever after books.

>11 thorold: >12 labfs39: Also a favourite book of mine for reasons you've both given. I'm not fond of happily ever after books.

15dchaikin

>13 thorold: I blame the Lais for that conditioning.

It took some time, but I worked through your fascinating March and now yachting April (Moscow is a very odd place to yacht, but it does keep with the little viking tracking that seems to be running through the book.) Admiring all your coursing through.

It took some time, but I worked through your fascinating March and now yachting April (Moscow is a very odd place to yacht, but it does keep with the little viking tracking that seems to be running through the book.) Admiring all your coursing through.

16thorold

>15 dchaikin: Sorry March was so long! Only a little bit of sailing in this next one...

This was added to the TBR pile the same day as >8 thorold:. The two together amount to about 10% of the total book-days in the pile. The next oldest after these was added on 18 April 2012, so at least for the next nine days I can say there's nothing over ten years old on the pile...

I think it sat so long on the pile because I picked it up in the charity shop after having enjoyed other books by the same author (mostly the Latin American trilogy) rather than because I was particularly interested in reading this one. You need a bit more than that before you commit yourself to 800 pages of war and disaster. It might've been a good one to take on a long flight, but somehow I never thought of that.

Birds without wings (2004) by Louis de Bernières (UK, 1954- )

This historical novel takes us through the momentous bit of Turkish history between 1900 and 1923, with the narrative viewpoint alternating between a helicopter-view of the big events of the career of Mustafa Kemal and a tortoise's-eye-view of the inhabitants of a remote, small town on the Anatolian coast near Fethiye (then called Telmessos).

Rather like Ivo Andrić in The bridge on the Drina, de Bernières shows us the Ottoman Empire as a polity that for centuries made it possible for people of different faiths and ethnic backgrounds to live together in reasonable harmony and without slaughtering each other, even if that life involved a lot of poverty and deprivation for most of them, and no political or legal rights worth speaking of.

The Muslims and Greek Christians who live in Eskibahçe speak the same language, have all been living in Anatolia for centuries, intermarrying from time to time, and don't think of themselves as "Turks" and "Greeks" until nationalist agitators come along and tell them that's what they are. As far as de Bernières is concerned, the "historic grievances" that led to the Greek occupation of Anatolia and the subsequent mass deportations of 1923 had their origins in the political ambitions of people like Venizelos and Mustafa Kemal, amplified into a revenge-cycle by the sort of atrocities that take place automatically as soon as you start an armed conflict.

There is some great, if rather romanticised, storytelling in this book: the Eskibahçe characters are full of interesting human quirks, and de Bernières cleverly mixes in local colour and traditions. The descriptions of Gallipoli from the viewpoint of an Ottoman soldier in the trenches are gripping too. But the political rant in the narrator's own voice in the "history" chapters doesn't seem to work as well: de Bernières is (understandably) so angry at the abuses and humanitarian disasters that leaders on all sides allowed to happen that he makes a lot of sweeping accusations that go beyond the evidence he has shown us. We're inclined to believe his assertions that Kemal, Venizelos, Lloyd George and the Kaiser are a bunch of irresponsible murderous ruffians, of course, and that all Italians except Mussolini are saints, but it would be nicer to be allowed to draw our own conclusions rather than have to take that as axiomatic. And of course, the fact that we know this is a British writer speaking on behalf of Ottoman/Turkish/Greek characters doesn't help.

Oddly, the thing I noticed most about this book before reading it, the fact that it's nearly 800 pages long, didn't really seem to matter. The use of multiple different types of narration results in quite a bit of repetition, but it felt like the sort of book where you could just dig in and let all that wash over you. De Bernière's writing isn't the sort of thing where you have to read a sentence several times. It would probably work really well as an audiobook.

This was added to the TBR pile the same day as >8 thorold:. The two together amount to about 10% of the total book-days in the pile. The next oldest after these was added on 18 April 2012, so at least for the next nine days I can say there's nothing over ten years old on the pile...

I think it sat so long on the pile because I picked it up in the charity shop after having enjoyed other books by the same author (mostly the Latin American trilogy) rather than because I was particularly interested in reading this one. You need a bit more than that before you commit yourself to 800 pages of war and disaster. It might've been a good one to take on a long flight, but somehow I never thought of that.

Birds without wings (2004) by Louis de Bernières (UK, 1954- )

This historical novel takes us through the momentous bit of Turkish history between 1900 and 1923, with the narrative viewpoint alternating between a helicopter-view of the big events of the career of Mustafa Kemal and a tortoise's-eye-view of the inhabitants of a remote, small town on the Anatolian coast near Fethiye (then called Telmessos).

Rather like Ivo Andrić in The bridge on the Drina, de Bernières shows us the Ottoman Empire as a polity that for centuries made it possible for people of different faiths and ethnic backgrounds to live together in reasonable harmony and without slaughtering each other, even if that life involved a lot of poverty and deprivation for most of them, and no political or legal rights worth speaking of.

The Muslims and Greek Christians who live in Eskibahçe speak the same language, have all been living in Anatolia for centuries, intermarrying from time to time, and don't think of themselves as "Turks" and "Greeks" until nationalist agitators come along and tell them that's what they are. As far as de Bernières is concerned, the "historic grievances" that led to the Greek occupation of Anatolia and the subsequent mass deportations of 1923 had their origins in the political ambitions of people like Venizelos and Mustafa Kemal, amplified into a revenge-cycle by the sort of atrocities that take place automatically as soon as you start an armed conflict.

There is some great, if rather romanticised, storytelling in this book: the Eskibahçe characters are full of interesting human quirks, and de Bernières cleverly mixes in local colour and traditions. The descriptions of Gallipoli from the viewpoint of an Ottoman soldier in the trenches are gripping too. But the political rant in the narrator's own voice in the "history" chapters doesn't seem to work as well: de Bernières is (understandably) so angry at the abuses and humanitarian disasters that leaders on all sides allowed to happen that he makes a lot of sweeping accusations that go beyond the evidence he has shown us. We're inclined to believe his assertions that Kemal, Venizelos, Lloyd George and the Kaiser are a bunch of irresponsible murderous ruffians, of course, and that all Italians except Mussolini are saints, but it would be nicer to be allowed to draw our own conclusions rather than have to take that as axiomatic. And of course, the fact that we know this is a British writer speaking on behalf of Ottoman/Turkish/Greek characters doesn't help.

Oddly, the thing I noticed most about this book before reading it, the fact that it's nearly 800 pages long, didn't really seem to matter. The use of multiple different types of narration results in quite a bit of repetition, but it felt like the sort of book where you could just dig in and let all that wash over you. De Bernière's writing isn't the sort of thing where you have to read a sentence several times. It would probably work really well as an audiobook.

17lisapeet

>16 thorold: That's one I've had on the shelf forever too. Good to know it holds up—I'll hang on to it until I can read it.

18LolaWalser

The Muslims and Greek Christians who live in Eskibahçe speak the same language, have all been living in Anatolia for centuries, intermarrying from time to time, and don't think of themselves as "Turks" and "Greeks" until nationalist agitators come along and tell them that's what they are.

I don't buy this for a minute. It's a beloved trope of some Western historians, particularly Anglo with a jones for the Ottomans, that the Balkans were a mush of un-self-conscious sheep who didn't know what languages they spoke, whence they came, who they were. It's class-A racism in action and no more. And insofar ignorance was a factor in the lives of those peoples, it was due to those "benevolent" masters who for centuries kept them with terror and taxes rolling in the mud, without roads, without schools, without, as you note, "political or legal rights worth speaking of". And that's some enviable, desirable state of things? Funny, I don't hear them singing hosannas to the USSR.

Bernieres always sounded like trash and I guess this confirms it to me.

Sorry about grumbling.

I don't buy this for a minute. It's a beloved trope of some Western historians, particularly Anglo with a jones for the Ottomans, that the Balkans were a mush of un-self-conscious sheep who didn't know what languages they spoke, whence they came, who they were. It's class-A racism in action and no more. And insofar ignorance was a factor in the lives of those peoples, it was due to those "benevolent" masters who for centuries kept them with terror and taxes rolling in the mud, without roads, without schools, without, as you note, "political or legal rights worth speaking of". And that's some enviable, desirable state of things? Funny, I don't hear them singing hosannas to the USSR.

Bernieres always sounded like trash and I guess this confirms it to me.

Sorry about grumbling.

19thorold

>18 LolaWalser: It does seem plausible that Greek Christians in Asia Minor didn’t exactly identify with Athens as their cultural homeland until someone told them to do that (although most likely that someone was their priest), and Bernières does make a point of the almost total illiteracy under the Ottomans, but beyond that I’m sure you’re right, and there’s a lot of romantic wishful thinking in the whole thing.

ETA: I suppose it’s the classic conservative idea that if something bad happens it’s the result of unnecessary change, not a consequence of a previous unsatisfactory state.

ETA: I suppose it’s the classic conservative idea that if something bad happens it’s the result of unnecessary change, not a consequence of a previous unsatisfactory state.

20LolaWalser

>19 thorold:

Greeks knew they were Christian, Turks knew they were Muslim, the very concept of "intermarriage" and peaceful co-existence demands that there exist separate groups. People always know who they are, even if they ignore (don't know or suppress knowledge) of every ancestor exactly. The poor may be illiterate and kept so, but they had calendars and name days, familial histories which ensured that no Muhammad was born to a Greek and no George to a Muslim.

The Ottomans had zero interest in creating a melting pot, their whole taxation system and other exploitative measures depended on differential treatment of Muslims and the Christian reaya. To be sure, a small percentage of converts from Christianity was encouraged and necessary as vassals, but those tended to be carefully selected (basically from the rich).

As for the oppressed, the very poor etc. of course there are different strategies of survival, but those also don't mean some innocent primal state,, but on the contrary presuppose an ability to recognize and play with multiple identities. When Albanians gave Christian AND Muslim names to their children, they weren't doing this out of ignorance, but precisely because of specific knowledge.

One really ought to go look for the first instance when this "they didn't know who they were" claptrap arose and I bet you it wouldn't stand scrutiny today better than any of the anthropology of the "exotics".

Greeks knew they were Christian, Turks knew they were Muslim, the very concept of "intermarriage" and peaceful co-existence demands that there exist separate groups. People always know who they are, even if they ignore (don't know or suppress knowledge) of every ancestor exactly. The poor may be illiterate and kept so, but they had calendars and name days, familial histories which ensured that no Muhammad was born to a Greek and no George to a Muslim.

The Ottomans had zero interest in creating a melting pot, their whole taxation system and other exploitative measures depended on differential treatment of Muslims and the Christian reaya. To be sure, a small percentage of converts from Christianity was encouraged and necessary as vassals, but those tended to be carefully selected (basically from the rich).

As for the oppressed, the very poor etc. of course there are different strategies of survival, but those also don't mean some innocent primal state,, but on the contrary presuppose an ability to recognize and play with multiple identities. When Albanians gave Christian AND Muslim names to their children, they weren't doing this out of ignorance, but precisely because of specific knowledge.

One really ought to go look for the first instance when this "they didn't know who they were" claptrap arose and I bet you it wouldn't stand scrutiny today better than any of the anthropology of the "exotics".

21dchaikin

>20 LolaWalser: "One really ought to go look for the first instance when this "they didn't know who they were" claptrap arose and - would either be a really fun study and droll story of repetitive romantic leanings toward mythical golden ages.

>16 thorold: it is on audible, a 2004 edition.

>16 thorold: it is on audible, a 2004 edition.

22thorold

By chance, the next-oldest book on the TBR also took me to the Eastern Mediterranean, albeit a few decades later.

This one arrived on the pile on 18 April 2012, so it's a few days short of its tenth anniversary. The next-oldest after this is from May 2014, and then there's still one from 2015 and six from 2016, so I can definitely say I've dealt with the worst offenders. But I have to think of my old boss, who once complained in a department meeting that however hard we worked at improvements, there always seemed to be about half the department that was performing below average...

This was Hella Haasse's fourth novel. It doesn't seem to have been translated into English, as far as I can see, but there is a French version (Les initiés).

De ingewijden (1957) by Hella S. Haasse (Netherlands, 1918-2011)

Six characters — American, Dutch, German and Greek — are brought together by a variety of circumstances in a small Cretan mountain village in the summer of 1954, with the German occupation and the Civil War still fresh in everyone's memories. Haasse passes the point-of-view from one character to the next in a sort of relay-race pattern, with overlaps in which we are made to see how little one person knows of what's going on in another's life.

For each character, Haasse prompts us to think about what the transition from childhood into independent adult life really means, and how it doesn't always coincide with cultural norms or biological development. She asks how that goes together with the religious/cultural idea of "initiation" — is there a necessary modern counterpart to the mysteries of Eleusis? Probably not, it seems: the one character who explicitly thinks of himself as an initiate is the German deserter Helmuth, whose featureless working-class life was given meaning by entry into the rites of Nazism, but who has been driven out of his mind by exposure to the realities that the Nazi ideology unleashed.

As ever, Haasse doesn't give the reader an easy ride, but it's an interesting trip all the same, with a lot of incidental detail of 1950s Greece along the way, and some sharp social observation.

This one arrived on the pile on 18 April 2012, so it's a few days short of its tenth anniversary. The next-oldest after this is from May 2014, and then there's still one from 2015 and six from 2016, so I can definitely say I've dealt with the worst offenders. But I have to think of my old boss, who once complained in a department meeting that however hard we worked at improvements, there always seemed to be about half the department that was performing below average...

This was Hella Haasse's fourth novel. It doesn't seem to have been translated into English, as far as I can see, but there is a French version (Les initiés).

De ingewijden (1957) by Hella S. Haasse (Netherlands, 1918-2011)

Six characters — American, Dutch, German and Greek — are brought together by a variety of circumstances in a small Cretan mountain village in the summer of 1954, with the German occupation and the Civil War still fresh in everyone's memories. Haasse passes the point-of-view from one character to the next in a sort of relay-race pattern, with overlaps in which we are made to see how little one person knows of what's going on in another's life.

For each character, Haasse prompts us to think about what the transition from childhood into independent adult life really means, and how it doesn't always coincide with cultural norms or biological development. She asks how that goes together with the religious/cultural idea of "initiation" — is there a necessary modern counterpart to the mysteries of Eleusis? Probably not, it seems: the one character who explicitly thinks of himself as an initiate is the German deserter Helmuth, whose featureless working-class life was given meaning by entry into the rites of Nazism, but who has been driven out of his mind by exposure to the realities that the Nazi ideology unleashed.

As ever, Haasse doesn't give the reader an easy ride, but it's an interesting trip all the same, with a lot of incidental detail of 1950s Greece along the way, and some sharp social observation.

23thorold

Yesterday was a good day for finishing things off, it seems: I also finished this, which is one of the Victorian read-along books for Q2. I'm not capable of reading a crime novel slowly enough for a proper read-along, apparently. I read the first half in one session a couple of weeks ago, put it aside for a bit and then read the second half last night.

The law and the lady (1875) by Wilkie Collins (UK, 1824-1889)

Wilkie Collins is known as one of the inventors of the modern detective-story, and before this I'd only ever read his two most famous books, The Moonstone (1868) and The woman in white (1859).

The law and the lady pushes the detective story into new territory, by creating a situation in which an enterprising young woman finds herself investigating a murder mystery. It is probably also one of the first crime stories in which the main physical clue is obtained as a result of forensic archaeology (the investigators even set up a tent over their work-site, in the best traditions of TV detectives...). To recommend it even further to the modern reader, one of the main witnesses is a disabled person, and there is a minor (but quite visible) character who seems to be either Trans or Intersex in modern terms. And another character who goes off to do relief work on the fringes of the Spanish Civil War (no, not that Spanish Civil War, one of the other ones).

However, interesting as though all that is, it's undermined by the complex manoeuvres Collins deems necessary to justify the use of a female investigator. There's a whole, rather ridiculous Bluebeard's Castle story to get through — "As long as you don't try to find out what my Dark Secret is, we can have a happy marriage" — before we even find out about the real mystery Valeria will have to solve. Also, like Harriet Vane, Valeria always has a man in the background to do the heavy thinking for her. Her role seems to be more to run around prodding people into activity. Although Collins was by no means a conventional man in his own life, he does seem to put a lot of very conventional Victorian (male) ideas about women into his portrait of Valeria, and she's ultimately not all that convincing.

Moreover, Collins obviously became too fond of his eccentric, wheelchair-bound misanthrope Miserrimus Dexter, and we spend far too much of the second part of the book being shown what an extraordinary creature he is, without any of it advancing the story very much. This is fun for a while, but it soon turns into a kind of freak-show.

Interesting, certainly, but ultimately not all that successful either as a novel or as a detective story.

The law and the lady (1875) by Wilkie Collins (UK, 1824-1889)

Wilkie Collins is known as one of the inventors of the modern detective-story, and before this I'd only ever read his two most famous books, The Moonstone (1868) and The woman in white (1859).

The law and the lady pushes the detective story into new territory, by creating a situation in which an enterprising young woman finds herself investigating a murder mystery. It is probably also one of the first crime stories in which the main physical clue is obtained as a result of forensic archaeology (the investigators even set up a tent over their work-site, in the best traditions of TV detectives...). To recommend it even further to the modern reader, one of the main witnesses is a disabled person, and there is a minor (but quite visible) character who seems to be either Trans or Intersex in modern terms. And another character who goes off to do relief work on the fringes of the Spanish Civil War (no, not that Spanish Civil War, one of the other ones).

However, interesting as though all that is, it's undermined by the complex manoeuvres Collins deems necessary to justify the use of a female investigator. There's a whole, rather ridiculous Bluebeard's Castle story to get through — "As long as you don't try to find out what my Dark Secret is, we can have a happy marriage" — before we even find out about the real mystery Valeria will have to solve. Also, like Harriet Vane, Valeria always has a man in the background to do the heavy thinking for her. Her role seems to be more to run around prodding people into activity. Although Collins was by no means a conventional man in his own life, he does seem to put a lot of very conventional Victorian (male) ideas about women into his portrait of Valeria, and she's ultimately not all that convincing.

Moreover, Collins obviously became too fond of his eccentric, wheelchair-bound misanthrope Miserrimus Dexter, and we spend far too much of the second part of the book being shown what an extraordinary creature he is, without any of it advancing the story very much. This is fun for a while, but it soon turns into a kind of freak-show.

Interesting, certainly, but ultimately not all that successful either as a novel or as a detective story.

24thorold

>22 thorold: >23 thorold: Those were reviews No. 1996 and 1997, so the issue of what to do with review No.2000 is getting closer. I’ve got a vaguely appropriate solution lined up, but I’m not completely committed yet…

25SassyLassy

>6 thorold: >24 thorold: It seems an almost impossible task to suggest something worthy of 2000 to someone with your 1999 other reviews, so I'm going with an author. Would someone like Borges make the cut?!

26thorold

>25 SassyLassy: Thanks, that’s a fun idea! Maybe not all of Borges in one go, I think that would be too much of a good thing, but there are one or two collections I haven’t read within living memory. Although I think Borges might call for something more mathematically interesting than a simple multiple of thousands. Maybe he should get the prime number 1999…? I already know what 1998 is going to be, but with a bit of restraint 1999 could still be El Libro de Arena.

Also, that makes me think “If Borges, why not Calvino or Bernhard…?” Austria’s leading grouch is the one who means the most to me personally, and there’s at least one major work I haven’t read yet.

I think I like that better than my original idea of books with explicit millennial references. Watch this space…

Also, that makes me think “If Borges, why not Calvino or Bernhard…?” Austria’s leading grouch is the one who means the most to me personally, and there’s at least one major work I haven’t read yet.

I think I like that better than my original idea of books with explicit millennial references. Watch this space…

27SassyLassy

>26 thorold: I like the idea of Borges as a prime number, plus I'm one of those who believes nnn9 is the end of a series, not nnn0.

Will stay tuned though.

Will stay tuned though.

28thorold

>27 SassyLassy: Borges is divisible only by himself and one!

29thorold

OK, here's No. 1998, picked for the Outcasts and Castaways theme read of Reading Globally:

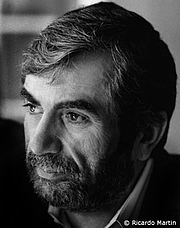

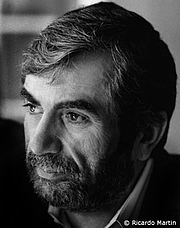

Michel Tournier became a translator and broadcaster as a fallback after failing to get an academic post in his first choice of career, philosophy. This, written at the age of 42, was his first published novel, and an immediate success, winning him the Grand Prix du Roman de l'Académie française. His second novel, Le Roi des aulnes, won the Prix Goncourt in 1970.

(Tournier wrote a further — "better", not "abridged", he said — version of the Robinson Crusoe story for children, under the title Vendredi, ou la vie sauvage, in 1971)

Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique (1967; Friday, or the other island) by Michel Tournier (France, 1924-2016)

Where J M Coetzee's Foe is a playful reworking of the Robinson Crusoe story informed by late-20th-century ideas about gender, colonialism, and how narratives are created, Tournier's version is — as you might expect — a philosophical exploration of where the solitary castaway stands in a post-Sartre world in which "hell is other people". Does the world have any existence outside our own perceptions if there are no other people to challenge those perceptions?

Tournier starts out with a fairly straightforward recap of Defoe's picture of the indefatigable British capitalist gritting his teeth to re-create all the elements of a productive economy — except sexuality — on his uninhabited island, then gradually subverts it, as Robinson becomes obsessed with the technology of production and creates vast excesses of agricultural products he has no use or market for. And of course his Robinson is not an asexual being like Defoe's, but finds himself experimenting with various kinds of sexual relationship with the island of Speranza herself. What could be more 1960s than X-certificate tree-hugging..?

Robinson's rescue of Friday from the human sacrifice he's been designated for is an accident — Robinson has already made the rational decision to side with the stronger party, but his bullet goes astray — but the entry of this new person into the island is the key moment in Robinson's philosophical release from his previous life. Friday starts out as the willing slave, but he has something Robinson lacks, being prepared to commit himself to projects without a utilitarian purpose — in particular, to create playful works of art. This ends up transforming the way both of them see the world. It liberates Friday to return to a new life as a full-fledged adult, and it brings Robinson into a meaningful spiritual communion with the island, free from his capitalist baggage.

———

Sadly, this book didn't do anything to resolve one of the greatest mysteries of French literature: where on earth did someone get the idea of turning Crusoe into Crusoé (and Poe into Poé, but not Defoe into Defoé...)?

As an alumnus of that institution myself, I was pleased but slightly puzzled to see Tournier making his 18th century Robinson a graduate of the University of York (est.1963)...

Michel Tournier became a translator and broadcaster as a fallback after failing to get an academic post in his first choice of career, philosophy. This, written at the age of 42, was his first published novel, and an immediate success, winning him the Grand Prix du Roman de l'Académie française. His second novel, Le Roi des aulnes, won the Prix Goncourt in 1970.

(Tournier wrote a further — "better", not "abridged", he said — version of the Robinson Crusoe story for children, under the title Vendredi, ou la vie sauvage, in 1971)

Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique (1967; Friday, or the other island) by Michel Tournier (France, 1924-2016)

Where J M Coetzee's Foe is a playful reworking of the Robinson Crusoe story informed by late-20th-century ideas about gender, colonialism, and how narratives are created, Tournier's version is — as you might expect — a philosophical exploration of where the solitary castaway stands in a post-Sartre world in which "hell is other people". Does the world have any existence outside our own perceptions if there are no other people to challenge those perceptions?

Tournier starts out with a fairly straightforward recap of Defoe's picture of the indefatigable British capitalist gritting his teeth to re-create all the elements of a productive economy — except sexuality — on his uninhabited island, then gradually subverts it, as Robinson becomes obsessed with the technology of production and creates vast excesses of agricultural products he has no use or market for. And of course his Robinson is not an asexual being like Defoe's, but finds himself experimenting with various kinds of sexual relationship with the island of Speranza herself. What could be more 1960s than X-certificate tree-hugging..?

Robinson's rescue of Friday from the human sacrifice he's been designated for is an accident — Robinson has already made the rational decision to side with the stronger party, but his bullet goes astray — but the entry of this new person into the island is the key moment in Robinson's philosophical release from his previous life. Friday starts out as the willing slave, but he has something Robinson lacks, being prepared to commit himself to projects without a utilitarian purpose — in particular, to create playful works of art. This ends up transforming the way both of them see the world. It liberates Friday to return to a new life as a full-fledged adult, and it brings Robinson into a meaningful spiritual communion with the island, free from his capitalist baggage.

———

Sadly, this book didn't do anything to resolve one of the greatest mysteries of French literature: where on earth did someone get the idea of turning Crusoe into Crusoé (and Poe into Poé, but not Defoe into Defoé...)?

As an alumnus of that institution myself, I was pleased but slightly puzzled to see Tournier making his 18th century Robinson a graduate of the University of York (est.1963)...

30FlorenceArt

I read Vendredi ou les limbes du pacifique in high school and loved it, but of course I don’t remember anything you mention, except the x-rated tree hugging and weird venereal disease ;-)

31thorold

>30 FlorenceArt: Yes, I'm sure that would have stuck in my mind as well if we'd got to read anything as sensational as that at school!

---

On to review No.1999, inspired by SassyLassy's suggestion above. This is the fifth of Borges's six collections of stories — I've (re-)read the first four fairly recently, but I've still to get to the sixth, La memoria de Shakespeare.

El libro de arena (1975; The book of sand) by Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina, 1899-1986)

I suppose this has pretty much everything you would expect from a Borges collection: paradoxes, gauchos, world-domination conspiracies, minor academic controversies, ironic fairy tales about skalds and their kings, a magic book with no first or last page, and a supernatural creature we don't get to meet.

The two really well-known pieces are obviously the title story about the frighteningly infinite book (which obviously complements the infinite library we met thirty years earlier) and "El otro", in which the seventy-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, sitting on a bench by the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hears someone whistling a familiar old Argentinian tune and discovers that he is sharing the bench with the the twenty-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, who as far as he knows is sitting on a bench in Geneva. Cue a delightfully perplexed exchange about which of them is dreaming this, and how they could tell.

There are two stories that deal in different ways with the idea that it might be possible to concentrate a poem into a single word, there is an account of the beliefs of a heretical Christian sect that didn't exist but probably should have, there is an old man's story of how he witnessed the shooting of the celebrated gaucho Juan Moreira on the same night he had his first sexual experience, there is a Nordic love-story set on the banks of the Ouse, there are hints of a Nordic theme touching all the stories in the book, and altogether there is far more than could possibly fit into a relatively slim little book. Obviously Borges lent his publishers some of his book-deforming magic. Wonderful stuff, however it was done.

---

On to review No.1999, inspired by SassyLassy's suggestion above. This is the fifth of Borges's six collections of stories — I've (re-)read the first four fairly recently, but I've still to get to the sixth, La memoria de Shakespeare.

El libro de arena (1975; The book of sand) by Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina, 1899-1986)

I suppose this has pretty much everything you would expect from a Borges collection: paradoxes, gauchos, world-domination conspiracies, minor academic controversies, ironic fairy tales about skalds and their kings, a magic book with no first or last page, and a supernatural creature we don't get to meet.

The two really well-known pieces are obviously the title story about the frighteningly infinite book (which obviously complements the infinite library we met thirty years earlier) and "El otro", in which the seventy-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, sitting on a bench by the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hears someone whistling a familiar old Argentinian tune and discovers that he is sharing the bench with the the twenty-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, who as far as he knows is sitting on a bench in Geneva. Cue a delightfully perplexed exchange about which of them is dreaming this, and how they could tell.

There are two stories that deal in different ways with the idea that it might be possible to concentrate a poem into a single word, there is an account of the beliefs of a heretical Christian sect that didn't exist but probably should have, there is an old man's story of how he witnessed the shooting of the celebrated gaucho Juan Moreira on the same night he had his first sexual experience, there is a Nordic love-story set on the banks of the Ouse, there are hints of a Nordic theme touching all the stories in the book, and altogether there is far more than could possibly fit into a relatively slim little book. Obviously Borges lent his publishers some of his book-deforming magic. Wonderful stuff, however it was done.

32dianeham

>29 thorold: a favorite of mine.

33thorold

All this fuss about 2000 reviews, and I didn’t even notice that it was my 15-year Thingaversary yesterday! Anyway, I seem to have been acting on it unconsciously: at least seven books added to my library in the last week…

I’m about a third of the way through the book I’m planning to review as No. 2000, anyway, so I’ll have to add a bit of a retrospective when I post that review. And then read some of the others that have been stacking up in the empty space I created by chopping off the oldest bit of the TBR…

I’m about a third of the way through the book I’m planning to review as No. 2000, anyway, so I’ll have to add a bit of a retrospective when I post that review. And then read some of the others that have been stacking up in the empty space I created by chopping off the oldest bit of the TBR…

35thorold

...and finally, the big reveal. Or not: I don't suppose anyone has been waiting for this with bated breath. But anyway, it felt kind of appropriate to mark my 2000th review on LT by reading my 20th book by an author who has come to mean a lot to me, and whom I somehow never came across until after joining LT. My Thomas Bernhard adventure started in December 2011 (nearly four years after joining LT) with the first parts of the Autobiography. Since then I've been working my way through novels, poems, and essays (only one play so far). A few more books still to go, but I will probably ration them out to last me a few more years.

Auslöschung : ein Zerfall (1986; Extinction) by Thomas Bernhard (Austria, 1931-1989)

Clearly, Bernhard's narrator in this novel, Franz-Josef Murau, Austrian exile in Rome, shares a lot of attributes with his creator. He's given to long, and often hilarious and self-contradictory diatribes, in particular against the "Catholic-National-Socialist" culture of Austria, against his family, against many aspects of the modern world, against aristocrats, against the ill-bred, against philistines, and against people who have an exaggerated devotion to "culture". He receives an urgent telegram on the opening page of the novel and doesn't start thinking about what to do in response until about 300 pages in, at the very end of the first part. In the second half of the book he also has one fundamental problem to resolve, and he deals with it in a couple of lines on the last page, after another 300 pages or so of talking about other things. As always in a Thomas Bernhard novel, it's not about the plot.

What it is about, as the title suggests, is a Schopenhauer-inspired project to deal with — extinguish — the bad stuff in Murau's head by expressing it all. This is a novel that aims for self-destruction, or at least the annihilation of the narrator. Murau is out to free himself from the shadow of his unloving, aristocratic parents (killed, together with Murau's elder brother, in a car accident just before the opening of the novel) with their unpleasant Nazi and Catholic connections, from the philistine, money-centred atmosphere at Wolfsegg Castle, from his outdoorsy brother, from his snooty sisters, one of whom has just married a Weinflaschenstöpselfabrikant (wine bottle stopper manufacturer — Bernhard clearly loves this superb German word, and uses it with increasing degrees of irony every time the unfortunate brother-in-law is mentioned) from Baden, and from Austria in general.

Of course, Bernhard doesn't want us to take it all completely at face value: we are shown that Murau has picked up much more of his family's snobbish attitudes than he is aware of, and particularly when he starts to realise that he has inherited Wolfsegg, he starts to act in some very country-landowner-like ways towards his sisters and the estate workers. We also have to decide for ourselves whether Murau's mother was really having an affair with the super-suave Vatican diplomat Archbishop Spadolini, or whether this is another bit of paranoia on his part.

As usual with Bernhard, there's at least a suspicion that he's put some of his friends and enemies into the book. Murau's Rome friend and critic, the eccentric poet Maria, is obviously based on Ingeborg Bachmann (who died some ten years before this was written); I'm sure there are some more characters who would be recognisable to readers in the know. And of course the whole topic of the Austrian upper classes closing ranks to protect former Nazis was very current in 1985-86 because of the Kurt Waldheim scandal.

Basically, this is six hundred pages of top-quality sardonic Bernhard prose. We don't have to like anyone in the book, or even take a particular interest in the fate of Wolfsegg, but we can sit back and enjoy it all from a safe distance.

Auslöschung : ein Zerfall (1986; Extinction) by Thomas Bernhard (Austria, 1931-1989)

Meine Übertreibungskunst habe ich so weit geschult, daß ich mich ohne weiteres den größten Übertreibungskünstler, der mir bekannt ist, nennen kann. Ich kenne keinen andern. Kein Mensch hat seine Übertreibungskunst jemals so auf die Spitze getrieben, habe ich zu Gambetti gesagt und darauf, daß ich, wenn man mich kurzerhand einmal fragen wollte, was ich denn eigentlich und insgeheim sei, doch darauf nur antworten könne, der größte Übertreibungskünstler, der mir bekannt ist.(Free translation: I have trained my art of exaggeration to such an extent that I can simply call myself the greatest exaggeration-artist that I know of. I don't know any other. No one has ever taken their art of exaggeration to such an extreme, I said to Gambetti, and if someone wanted to ask me some time what I actually am in my secret self, I could only answer, the greatest exaggeration-artist who is known to me.)

Clearly, Bernhard's narrator in this novel, Franz-Josef Murau, Austrian exile in Rome, shares a lot of attributes with his creator. He's given to long, and often hilarious and self-contradictory diatribes, in particular against the "Catholic-National-Socialist" culture of Austria, against his family, against many aspects of the modern world, against aristocrats, against the ill-bred, against philistines, and against people who have an exaggerated devotion to "culture". He receives an urgent telegram on the opening page of the novel and doesn't start thinking about what to do in response until about 300 pages in, at the very end of the first part. In the second half of the book he also has one fundamental problem to resolve, and he deals with it in a couple of lines on the last page, after another 300 pages or so of talking about other things. As always in a Thomas Bernhard novel, it's not about the plot.

What it is about, as the title suggests, is a Schopenhauer-inspired project to deal with — extinguish — the bad stuff in Murau's head by expressing it all. This is a novel that aims for self-destruction, or at least the annihilation of the narrator. Murau is out to free himself from the shadow of his unloving, aristocratic parents (killed, together with Murau's elder brother, in a car accident just before the opening of the novel) with their unpleasant Nazi and Catholic connections, from the philistine, money-centred atmosphere at Wolfsegg Castle, from his outdoorsy brother, from his snooty sisters, one of whom has just married a Weinflaschenstöpselfabrikant (wine bottle stopper manufacturer — Bernhard clearly loves this superb German word, and uses it with increasing degrees of irony every time the unfortunate brother-in-law is mentioned) from Baden, and from Austria in general.

Of course, Bernhard doesn't want us to take it all completely at face value: we are shown that Murau has picked up much more of his family's snobbish attitudes than he is aware of, and particularly when he starts to realise that he has inherited Wolfsegg, he starts to act in some very country-landowner-like ways towards his sisters and the estate workers. We also have to decide for ourselves whether Murau's mother was really having an affair with the super-suave Vatican diplomat Archbishop Spadolini, or whether this is another bit of paranoia on his part.

As usual with Bernhard, there's at least a suspicion that he's put some of his friends and enemies into the book. Murau's Rome friend and critic, the eccentric poet Maria, is obviously based on Ingeborg Bachmann (who died some ten years before this was written); I'm sure there are some more characters who would be recognisable to readers in the know. And of course the whole topic of the Austrian upper classes closing ranks to protect former Nazis was very current in 1985-86 because of the Kurt Waldheim scandal.

Basically, this is six hundred pages of top-quality sardonic Bernhard prose. We don't have to like anyone in the book, or even take a particular interest in the fate of Wolfsegg, but we can sit back and enjoy it all from a safe distance.

36thorold

So, fifteen years of LT and 2000 reviews, that comes to an average of 133 reviews a year, which makes sense: that's about how many books I tend to read in a year. I have been reviewing everything I read "from cover to cover" during most of that time, although at the beginning, before we got Collections, I don't think I was reviewing unowned books.

According to the LT Zeitgeist, that makes me the 152nd most prolific reviewer on LT. I shall certainly put that on my CV... :-)

For well-known reasons, Thumb-counts aren't a very reliable way of judging how others perceive the quality of my reviews, but they do give me at least a very coarse indication. From a quick (and possibly inaccurate) count, it looks as though 841/2000 reviews (42%) have been thumbed by at least one LT member, with a total of 1446 thumbs, or 1.7 per thumbed review. I'm happy with that, especially given the rather wide range of what I read, which means I don't have a big overlap with any one mutual backscratching group.

Most likely to be thumbed, as far as I can see, are reviews of new publications, history books, German novels, and books I reviewed a long time ago. Obviously at least some of that must reflect the thumbing habits of a few specific individuals (thank you, whoever you are!). Joke reviews and parodies seem to get more thumbs than serious ones, which is probably fair, because it takes more effort to be funny than to be informative. And reviews with a lot of thumbs tend to attract more thumbs.

According to the LT Zeitgeist, that makes me the 152nd most prolific reviewer on LT. I shall certainly put that on my CV... :-)

For well-known reasons, Thumb-counts aren't a very reliable way of judging how others perceive the quality of my reviews, but they do give me at least a very coarse indication. From a quick (and possibly inaccurate) count, it looks as though 841/2000 reviews (42%) have been thumbed by at least one LT member, with a total of 1446 thumbs, or 1.7 per thumbed review. I'm happy with that, especially given the rather wide range of what I read, which means I don't have a big overlap with any one mutual backscratching group.

Most likely to be thumbed, as far as I can see, are reviews of new publications, history books, German novels, and books I reviewed a long time ago. Obviously at least some of that must reflect the thumbing habits of a few specific individuals (thank you, whoever you are!). Joke reviews and parodies seem to get more thumbs than serious ones, which is probably fair, because it takes more effort to be funny than to be informative. And reviews with a lot of thumbs tend to attract more thumbs.

37AnnieMod

>36 thorold: Congrats! :) And Happy 15th Thingaversary. Ha - I seem to be turning into a teenager (13) in 4 days. I feel like a baby now :)

>35 thorold: Interesting review. I had never read anything by this author (or heard of him)... any recommendation for a first book by him?

>35 thorold: Interesting review. I had never read anything by this author (or heard of him)... any recommendation for a first book by him?

38avaland

>36 thorold: Happy Thingaversary!! and thanks for hanging around; I think we have all enjoy your reading exploits. Nice stats. And interesting notes on what reviews gets thumbs up. I find the star rating feature not very useful. I'm always horrified to see a splendid piece of literature given 2 stars, because the reader was not well-matched to the book or author, or wasn't up to stretching themselves.

.

.

39thorold

>37 AnnieMod: The way I got started with Bernhard was the Autobiography, which is five separate novella-sized parts in German but seems to come as a bundle (Gathering evidence) in English. I think that's a good way in: it's much less intimidating than the full-length novels, and easier to give a context to than some of the novellas/essays. And it's very interesting in its own right, lots of good stuff about growing up illegitimate in thirties Bavaria and Salzburg, and more shopkeeping than Kipps.

Otherwise, the posthumous essay collections My prizes and Goethe dies are both short, sardonic and very funny.

If you want to try one of the novels, Woodcutters or Old masters might be the best to try first. I wouldn't go for The loser right away, even though it seems to be the most popular on LT.

Otherwise, the posthumous essay collections My prizes and Goethe dies are both short, sardonic and very funny.

If you want to try one of the novels, Woodcutters or Old masters might be the best to try first. I wouldn't go for The loser right away, even though it seems to be the most popular on LT.

40AnnieMod

>39 thorold: Thanks! The local library has My Prizes which makes than an easy choice I guess. :) That autobiography does sound interesting though...

41LolaWalser

Those are some smashing numbers, congratulations! Older reviews have more thumbs because more people participated in LT in the beginning.

42japaul22

I've just started looking for some Austrian authors to read before a trip to Vienna this summer. I've never read Thomas Bernhard and think Old Masters looks like a good one to try.

Thanks for sharing your reviews! I am sometimes overwhelmed by both the amount of books you read and the quality of the books you read, but I always look forward to new posts on your thread.

Thanks for sharing your reviews! I am sometimes overwhelmed by both the amount of books you read and the quality of the books you read, but I always look forward to new posts on your thread.

43rocketjk

Very cool LT accomplishments. I always enjoy your reviews. 133 a year! That's some productive page turning!

44thorold

Thanks, all! Being congratulated for staying in the same place for a long time always feels a bit unearned somehow, but I am really glad I found LT 15 years ago, and that so many interesting and sympathetic other people also found it.

>42 japaul22: I’ve read far too many Austrians for someone with no particular connection to the country. If you try Bernhard and like him, then for a musician it’s pretty much compulsory to read The loser.

If you haven’t tried them yet, when you’re making your list you might also want to have a look at Joseph Roth, Ingeborg Bachmann, Elfriede Jelinek, Marlen Haushofer and — for someone a bit more contemporary — Robert Seethaler…

>42 japaul22: I’ve read far too many Austrians for someone with no particular connection to the country. If you try Bernhard and like him, then for a musician it’s pretty much compulsory to read The loser.