Ce sujet est actuellement indiqué comme "en sommeil"—le dernier message date de plus de 90 jours. Vous pouvez le réveiller en postant une réponse.

1wandering_star

Looking forward to more good reading, and discussion of books, on Club Read 2019.

I don't generally set myself reading goals (and if I do, I don't stick to them) but I am hoping to read a lot of physical books this year - I'd like to end the year with no more books than fit on my shelves. (I have a lot of shelves, so this is doable, if I mainly read my own books and don't acquire too many more...!)

Top reads of 2018:

Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner

The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes

Circe by Madeline Miller

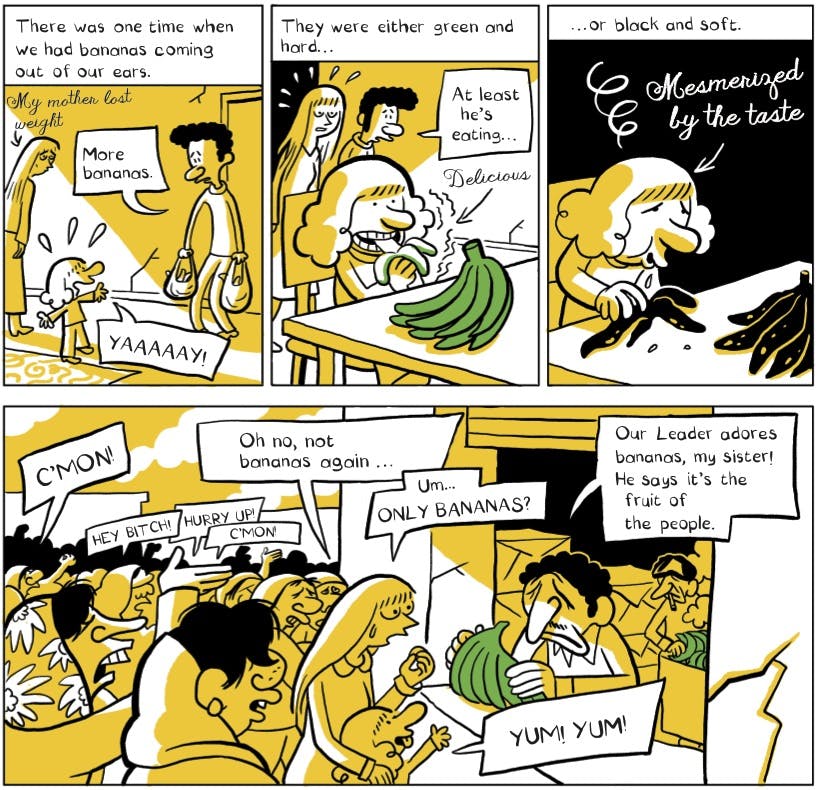

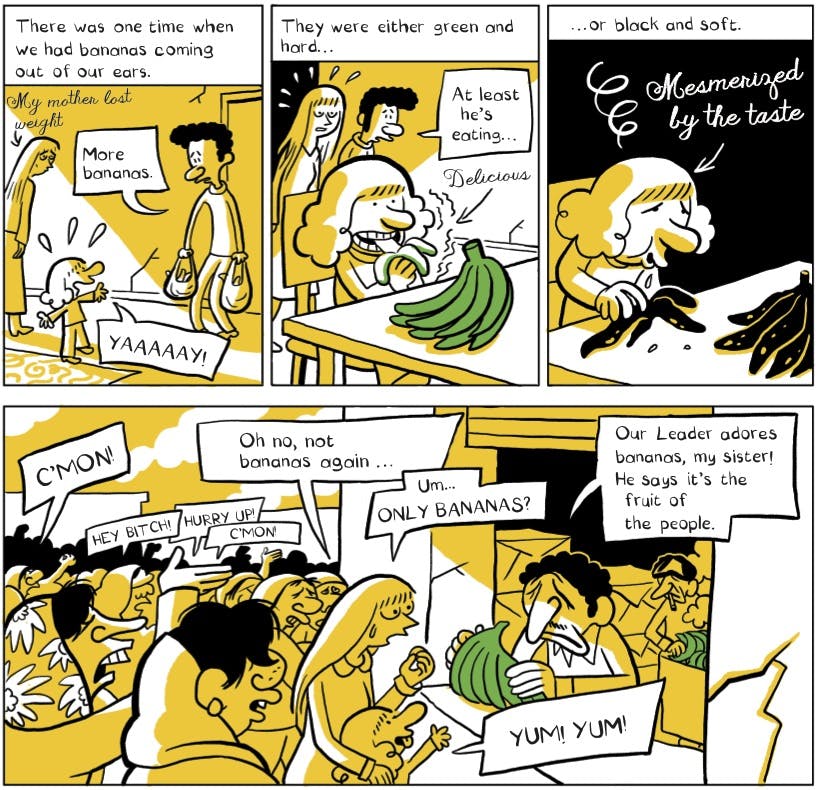

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui

The Gallows Pole by Benjamin Myers

plus honourable mentions for:

The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver

Time Present and Time Past by Deirdre Madden

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard

Favourite non-fiction:

Tinderbox by Megan Dunn (creative non-fiction)

I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong (popular science)

I don't generally set myself reading goals (and if I do, I don't stick to them) but I am hoping to read a lot of physical books this year - I'd like to end the year with no more books than fit on my shelves. (I have a lot of shelves, so this is doable, if I mainly read my own books and don't acquire too many more...!)

Top reads of 2018:

Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner

The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes

Circe by Madeline Miller

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui

The Gallows Pole by Benjamin Myers

plus honourable mentions for:

The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver

Time Present and Time Past by Deirdre Madden

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard

Favourite non-fiction:

Tinderbox by Megan Dunn (creative non-fiction)

I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong (popular science)

4wandering_star

It's been a very busy start to the year, both personally and at work, which is why I haven't posted any reviews yet. Also, several of the books I've read so far this year have taken quite a long time to get through - or I haven't been able to get through them at all! In fact I just checked and I have abandoned half the books I have tried to read so far this year - which feels quite a high number. Still, some interesting reads within all that, so here goes with the reviews.

1. The New Spymasters: inside espionage from the Cold War to global terror by Stephen Grey

This purports to be a critical analysis of espionage, mainly focused on developments since the end of the Cold War - the question about what intelligence services are for after 'the end of history' (remember that?) and whether traditional human intelligence can be of any use against a dispersed, often self-radicalised threat, and how it stands up in an age of mass surveillance. It isn't quite that, but it is an interesting and entertaining history, with each chapter focusing on one particular case study to illustrate a wider point.

Trainee spymasters were told to analyse the 'target' and then guess what motive could be exploited to persuade him to become an agent and betray his country or employer. "That's all bullshit," Jim had said. "It never actually works like that. The key thing is to get the guy to betray something, to cross the line. He will work out his own justification." A carefully nurtured recruitment was often based on an unspoken understanding. Human beings had incredible ways of inventing rational excuses for what they did or were going to do, he said.

1. The New Spymasters: inside espionage from the Cold War to global terror by Stephen Grey

This purports to be a critical analysis of espionage, mainly focused on developments since the end of the Cold War - the question about what intelligence services are for after 'the end of history' (remember that?) and whether traditional human intelligence can be of any use against a dispersed, often self-radicalised threat, and how it stands up in an age of mass surveillance. It isn't quite that, but it is an interesting and entertaining history, with each chapter focusing on one particular case study to illustrate a wider point.

Trainee spymasters were told to analyse the 'target' and then guess what motive could be exploited to persuade him to become an agent and betray his country or employer. "That's all bullshit," Jim had said. "It never actually works like that. The key thing is to get the guy to betray something, to cross the line. He will work out his own justification." A carefully nurtured recruitment was often based on an unspoken understanding. Human beings had incredible ways of inventing rational excuses for what they did or were going to do, he said.

5wandering_star

2. Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver

Unsheltered weaves together the stories of two families, living in the same place at different times. This is not the only thing in common - both families are struggling economically, and have seen their expectations decline; and both live at a time of great national division - our contemporary experience, and just after the Civil War. Climate change is a topic of debate now - and Darwin's theories of evolution were the scientific controversy then.

Barbara Kingsolver is a great writer, but I think in this book she is too close to the subject she is writing about. The Lacuna, which I read last year, was in some ways also a critique of contemporary politics and policies - but because it was actually set in the mid-twentieth century, the critique didn't overwhelm the story. In Unsheltered, the family spend a lot of time talking and arguing about politics, in a way which is probably accurate but not very entertaining.

“That’s true,” Iano said. “You can’t really have civilisation without growth. It would be a zero-sum economy: I have needs, everyone has needs, and the only way I could gain something is to take it away from you.” “Dope scenario, Dad,” Tig said, “only the world is zero sum. When you take stuff out of the land and ocean, that’s taking. You’re just pretending there’s always going to be more, which there isn’t.

Unsheltered weaves together the stories of two families, living in the same place at different times. This is not the only thing in common - both families are struggling economically, and have seen their expectations decline; and both live at a time of great national division - our contemporary experience, and just after the Civil War. Climate change is a topic of debate now - and Darwin's theories of evolution were the scientific controversy then.

Barbara Kingsolver is a great writer, but I think in this book she is too close to the subject she is writing about. The Lacuna, which I read last year, was in some ways also a critique of contemporary politics and policies - but because it was actually set in the mid-twentieth century, the critique didn't overwhelm the story. In Unsheltered, the family spend a lot of time talking and arguing about politics, in a way which is probably accurate but not very entertaining.

“That’s true,” Iano said. “You can’t really have civilisation without growth. It would be a zero-sum economy: I have needs, everyone has needs, and the only way I could gain something is to take it away from you.” “Dope scenario, Dad,” Tig said, “only the world is zero sum. When you take stuff out of the land and ocean, that’s taking. You’re just pretending there’s always going to be more, which there isn’t.

6wandering_star

3. A Patient Fury by Sarah Ward

Crime. In an apparent murder-suicide, a family is killed - the evidence seems to suggest that the wife killed her husband and child, before setting fire to the house and hanging herself. The detective, however, is sure that there is more to the story.

Perfectly OK but I found the conclusion of the story very annoying -the detective turns out to be right all along - but her insistence that she is right is based on *no evidence whatsoever* except the fact that the usual pattern is not for this sort of crime to be committed by women. Which seemed to me not really enough for someone to upend the whole investigation and go rogue... Looking at the reviews, it seems this particular detective always does this, which means I won't be reading any more of this series.

Connie ended the call and marvelled at her ability to contain her fury. There was an important press conference and she wasn’t even going to be there even though she was here in the station already. If it had been Palmer who was to attend over her, she would have been spitting blood. The fact it was the calm and capable Matthews made it worse, however. She was being sidelined and all because she had dared to challenge the perceived narrative of events. Francesca was going to be paraded throughout the media as a monster, a killer of children, her children, and a mass murderer, and no one seemed to have a problem that there was no evidence whatsoever of why she might have done so.

Crime. In an apparent murder-suicide, a family is killed - the evidence seems to suggest that the wife killed her husband and child, before setting fire to the house and hanging herself. The detective, however, is sure that there is more to the story.

Perfectly OK but I found the conclusion of the story very annoying -

Connie ended the call and marvelled at her ability to contain her fury. There was an important press conference and she wasn’t even going to be there even though she was here in the station already. If it had been Palmer who was to attend over her, she would have been spitting blood. The fact it was the calm and capable Matthews made it worse, however. She was being sidelined and all because she had dared to challenge the perceived narrative of events. Francesca was going to be paraded throughout the media as a monster, a killer of children, her children, and a mass murderer, and no one seemed to have a problem that there was no evidence whatsoever of why she might have done so.

7wandering_star

4. The Emperor's Children by Claire Messud

This title comes from "The Emperor's Children Have No Clothes", which is a book written by Marina, one of the characters in the novel. It's a book about the social significance of children's clothes - but it could also be a description of herself and her social circle. Marina's father is a renowned public intellectual, and Marina has always coasted on that fact, and on her beauty. Her two close friends, Julius and Danielle, are also working in media, trying to make a name for themselves and to live up to the potential they believe they have.

Meanwhile, Marina's father, Murray Thwaite, is such a lion that everyone has a strong opinion about him - and it's probably this which most drives the events in the book. Murray's nephew is ten years younger than Marina and her friends, but has the same belief that he has a genius which ought to be recognised: his mantra is an Emerson quote, "Great geniuses have the shortest biographies. Their cousins can tell you nothing about them. They lived in their writings, and so their house and street life was trivial and commonplace." But once he comes to spend time with Murray and his family, he feels out-of-place and discovers that his idol has feet of clay. At the same time, an iconoclastic young Australian is hoping to make a name for himself with a dramatic take-down of Murray - and hires Marina to work on his new magazine.

The book is essentially a depiction of a particular stratum of New York society. It's pretty well-written, but I wasn't very interested in any of the characters - which made the 580 pages something of a slog.

Danielle reflected that growing up, coupling, was a process of growing away from mirth, as if, like an amphibian, one ceased to breathe in the same way: laughter, once vital sustenance, protean relief and all that made isolation and struggle and fear bearable, was replaced by the stolid matter of stability: nominally content, resigned and unafraid, one grew to fear jokes and their capacity to unsettle.

This title comes from "The Emperor's Children Have No Clothes", which is a book written by Marina, one of the characters in the novel. It's a book about the social significance of children's clothes - but it could also be a description of herself and her social circle. Marina's father is a renowned public intellectual, and Marina has always coasted on that fact, and on her beauty. Her two close friends, Julius and Danielle, are also working in media, trying to make a name for themselves and to live up to the potential they believe they have.

Meanwhile, Marina's father, Murray Thwaite, is such a lion that everyone has a strong opinion about him - and it's probably this which most drives the events in the book. Murray's nephew is ten years younger than Marina and her friends, but has the same belief that he has a genius which ought to be recognised: his mantra is an Emerson quote, "Great geniuses have the shortest biographies. Their cousins can tell you nothing about them. They lived in their writings, and so their house and street life was trivial and commonplace." But once he comes to spend time with Murray and his family, he feels out-of-place and discovers that his idol has feet of clay. At the same time, an iconoclastic young Australian is hoping to make a name for himself with a dramatic take-down of Murray - and hires Marina to work on his new magazine.

The book is essentially a depiction of a particular stratum of New York society. It's pretty well-written, but I wasn't very interested in any of the characters - which made the 580 pages something of a slog.

Danielle reflected that growing up, coupling, was a process of growing away from mirth, as if, like an amphibian, one ceased to breathe in the same way: laughter, once vital sustenance, protean relief and all that made isolation and struggle and fear bearable, was replaced by the stolid matter of stability: nominally content, resigned and unafraid, one grew to fear jokes and their capacity to unsettle.

8wandering_star

5. Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck

Richard is a university professor. He's an unemotional type: once, in 1990 when the Berlin Wall came down, he walked across the place where it had blocked his road - a crowd of West Berliners were waiting there to welcome Easterners, but Richard was only interested in finding a shorter route to work, and pushed through them grumpily. Shortly after his retirement, he walks past what turns out to be a protest by asylum seekers, who are asking for the right to stay and work in Germany. He becomes intrigued, and starts to spend more time with the men. At first, it's more of an academic interest, but as he gets to know them, he gets more involved and engaged in their lives. In some ways, he, too, is dislocated - he grew up in a country which no longer exists, and has retired from the job which gave his life shape and meaning.

As it is, everything his wife always referred to as his 'stuff' now exists for his pleasure alone. Sure, some used book dealer will probably take his library, and a few volumes - a first edition, a signed copy - might wind up on the shelf of a bibliophile. Someone who, like him, is permitted to accumulate 'stuff' during his lifetime. And so the cycle will continue. But everything else? All these objects surrounding him form a system and have meaning only as long as he makes his way among them with his habitual gestures, remembering this, remembering that - and once he's gone, they'll drift apart and be lost. That's another thing he could write about sometime: the gravitational force that unites lifeless objects and living creatures to form a world. Is he a sun? He'll have to be careful not to lose his marbles now that he's going to be spending entire days alone without anyone to talk to.

Richard is a university professor. He's an unemotional type: once, in 1990 when the Berlin Wall came down, he walked across the place where it had blocked his road - a crowd of West Berliners were waiting there to welcome Easterners, but Richard was only interested in finding a shorter route to work, and pushed through them grumpily. Shortly after his retirement, he walks past what turns out to be a protest by asylum seekers, who are asking for the right to stay and work in Germany. He becomes intrigued, and starts to spend more time with the men. At first, it's more of an academic interest, but as he gets to know them, he gets more involved and engaged in their lives. In some ways, he, too, is dislocated - he grew up in a country which no longer exists, and has retired from the job which gave his life shape and meaning.

As it is, everything his wife always referred to as his 'stuff' now exists for his pleasure alone. Sure, some used book dealer will probably take his library, and a few volumes - a first edition, a signed copy - might wind up on the shelf of a bibliophile. Someone who, like him, is permitted to accumulate 'stuff' during his lifetime. And so the cycle will continue. But everything else? All these objects surrounding him form a system and have meaning only as long as he makes his way among them with his habitual gestures, remembering this, remembering that - and once he's gone, they'll drift apart and be lost. That's another thing he could write about sometime: the gravitational force that unites lifeless objects and living creatures to form a world. Is he a sun? He'll have to be careful not to lose his marbles now that he's going to be spending entire days alone without anyone to talk to.

9wandering_star

6. The Elusive Mrs Pollifax by Dorothy Gilman

This is the first book I've read featuring Mrs Pollifax - I'd never heard of the series outside some enthusiastic LT reviews. If you haven't heard of her either, the start of the back-cover blurb tells you all you need to know:

“When Mr Carstairs of the CIA once again had occasion to send Mrs Emily Pollifax off on a secret mission, he honestly thought that it would just be a simple tourist trip to Bulgaria. All she had to do was to smuggle in eight forged passports, craftily hidden away in a specially designed hat in the shape of a bird’s nest. But where Mrs Pollifax was concerned, nothing was ever that straightforward, and before long she found herself embroiled in a frightening international situation.”

This is basically a cosy spy thriller, if you can imagine such a thing - and a delightfully preposterous read.

‘I am wondering,’ said Mrs Pollifax thoughtfully, ‘if Panchevsy Institute’s reputation may not be our greatest asset. In my experience this sort of thing induces carelessness.’ Fixing Boris with a stern eye, she said, ‘After all, if you had a reputation like that - terrifying - what else would you need? You could relax.’

‘Already you are terrifying me ,’ Boris said. He smiled and the effect on his gloomy features was dazzling. ‘I think you must be like one of our witches in the Balkan mountains.’

(By the way, on the cover of my copy at least, Mrs P bears a strong resemblance to Camilla, Prince Charles' wife!)

This is the first book I've read featuring Mrs Pollifax - I'd never heard of the series outside some enthusiastic LT reviews. If you haven't heard of her either, the start of the back-cover blurb tells you all you need to know:

“When Mr Carstairs of the CIA once again had occasion to send Mrs Emily Pollifax off on a secret mission, he honestly thought that it would just be a simple tourist trip to Bulgaria. All she had to do was to smuggle in eight forged passports, craftily hidden away in a specially designed hat in the shape of a bird’s nest. But where Mrs Pollifax was concerned, nothing was ever that straightforward, and before long she found herself embroiled in a frightening international situation.”

This is basically a cosy spy thriller, if you can imagine such a thing - and a delightfully preposterous read.

‘I am wondering,’ said Mrs Pollifax thoughtfully, ‘if Panchevsy Institute’s reputation may not be our greatest asset. In my experience this sort of thing induces carelessness.’ Fixing Boris with a stern eye, she said, ‘After all, if you had a reputation like that - terrifying - what else would you need? You could relax.’

‘Already you are terrifying me ,’ Boris said. He smiled and the effect on his gloomy features was dazzling. ‘I think you must be like one of our witches in the Balkan mountains.’

(By the way, on the cover of my copy at least, Mrs P bears a strong resemblance to Camilla, Prince Charles' wife!)

10NanaCC

>9 wandering_star: I’ve enjoyed the three I’ve read so far. I always read a series in order, so this is the third I’ve read. If you haven’t read the first, The Unexpected Mrs Polifax, her accidentally becoming a CIA agent is quite funny. Preposterous, but they are fun to read or listen to.

11wandering_star

>10 NanaCC: Thanks! I own one other book in the series, but it isn't that one. I will look out for it.

12wandering_star

7. Milkman by Anna Burns

This is a really remarkable book. The story is that of a young woman - known to us only as Middle Sister - growing up in Northern Ireland during the height of the Troubles (although again, neither of these things are ever named). She only wants to stay out of political disputes, mind her own business, and read - but this is not an environment where someone can mind their own business, even more so once she comes to the attention of a senior paramilitary man, who does what we might now call stalking her (kerb-crawling as she walks home, running alongside her when she goes for a jog) - but she doesn't have that word for his behaviour either. And once it is known that he is paying her attention, the whole society around her makes up its mind that she must be involved with him, and judges her accordingly.

The book is absolutely airless, and the way it does that is through Middle Sister's use of language. The rules are unspoken - so much so that she can't even name them - but they are if anything stronger because of that. Middle Sister tells us about various individuals who tried to ignore the rules or live outside the sectarian disputes, but any attempt to do that is crushed by social pressure - for example, it's the early days of the feminist movement and a group of women tries to set up a small discussion group. They are first visited by the paramilitaries, and then the other women in the community tell the paramilitaries to back off - but only so that they can tackle the feminist group themselves.

Daily life is a minefield too:

There were neutral television programmes which could hail from ‘over the water’ or from ‘over the border’ yet be watched by everyone ‘this side of the road’ as well as ‘that side of the road’ without causing disloyalty in either community. Then there were programmes that could be watched without treason by one side whilst hated and detested ‘across the road’ on the other side. … There was food and drink. The right butter. The wrong butter. The tea of allegiance. The tea of betrayal. There were ‘our shops’ and ‘their shops’. Placenames, What school you went to. What prayers you said. What hymns you sand. How you pronounced your ‘haitch’ or ‘aitch’. Where you went to work. And of course there were bus-stops.

When this won the Booker there was a storm in a teacup over 'difficult books'. I don't really understand this. There's nothing particularly experimental about the structure or the story - it's only the way that language is used, which means that the reader has to think a bit. But it's precisely that which makes the book so powerful. If you want to be harshly critical, I think it could have been a little bit shorter. But I find it hard to imagine that this won't turn out to be one of my books of the year.

This is a really remarkable book. The story is that of a young woman - known to us only as Middle Sister - growing up in Northern Ireland during the height of the Troubles (although again, neither of these things are ever named). She only wants to stay out of political disputes, mind her own business, and read - but this is not an environment where someone can mind their own business, even more so once she comes to the attention of a senior paramilitary man, who does what we might now call stalking her (kerb-crawling as she walks home, running alongside her when she goes for a jog) - but she doesn't have that word for his behaviour either. And once it is known that he is paying her attention, the whole society around her makes up its mind that she must be involved with him, and judges her accordingly.

The book is absolutely airless, and the way it does that is through Middle Sister's use of language. The rules are unspoken - so much so that she can't even name them - but they are if anything stronger because of that. Middle Sister tells us about various individuals who tried to ignore the rules or live outside the sectarian disputes, but any attempt to do that is crushed by social pressure - for example, it's the early days of the feminist movement and a group of women tries to set up a small discussion group. They are first visited by the paramilitaries, and then the other women in the community tell the paramilitaries to back off - but only so that they can tackle the feminist group themselves.

Daily life is a minefield too:

There were neutral television programmes which could hail from ‘over the water’ or from ‘over the border’ yet be watched by everyone ‘this side of the road’ as well as ‘that side of the road’ without causing disloyalty in either community. Then there were programmes that could be watched without treason by one side whilst hated and detested ‘across the road’ on the other side. … There was food and drink. The right butter. The wrong butter. The tea of allegiance. The tea of betrayal. There were ‘our shops’ and ‘their shops’. Placenames, What school you went to. What prayers you said. What hymns you sand. How you pronounced your ‘haitch’ or ‘aitch’. Where you went to work. And of course there were bus-stops.

When this won the Booker there was a storm in a teacup over 'difficult books'. I don't really understand this. There's nothing particularly experimental about the structure or the story - it's only the way that language is used, which means that the reader has to think a bit. But it's precisely that which makes the book so powerful. If you want to be harshly critical, I think it could have been a little bit shorter. But I find it hard to imagine that this won't turn out to be one of my books of the year.

13AlisonY

>12 wandering_star: great review - I'm looking forward to getting to Milkman soon. I'm curious to see if it is very our N. Irish slang / dialect that makes this a read to concentrate on for some, or if it's just her style.

14dchaikin

Sorry your year has been so crazy. Enjoyed these. I plan to try Milkman on audio and now I’ll be thinking about the language.

15wandering_star

>13 AlisonY: I don't remember there being much slang - it's more that there are a lot of words that the narrator never uses (British, Irish, paramilitary, loyalist, republican etc) - sometimes she uses another word (eg the republicans are called 'renouncers') and sometimes she just talks around it.

16wandering_star

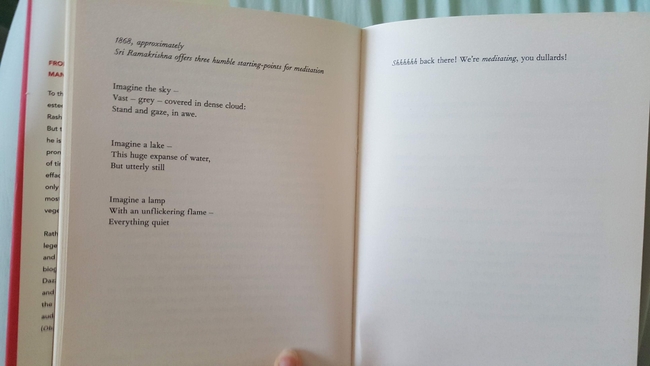

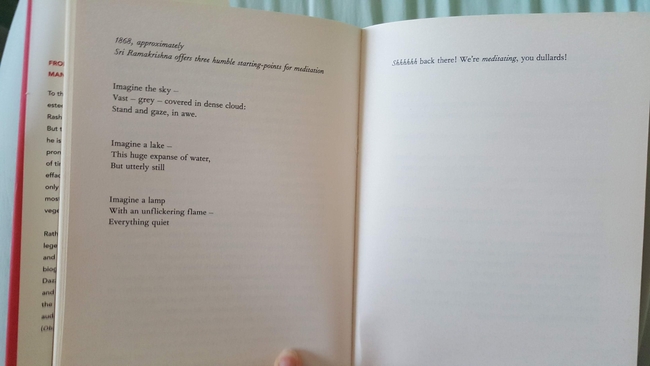

8. The Cauliflower by Nicola Barker

In The Cauliflower, Nicola Barker applies her trademark experimental style to describing the real life of Sri Ramakrishna - drawing on a lot of the existing texts about his life, his worship and his character.

I am a big fan of Nicola Barker - but I have to say this is not what I expected. It took me a long time to realise that it was her take on a true story, and I spent quite a lot of the book expecting the story to go in a particular direction - which it never did. In fact there is not that much story - if I was going to summarise the book, it basically said 'there was this guy and he had these crazy effects on the people that knew him'. And I am not at all interested in religious belief or mysticism, so learning about Ramakrishna's life was not that gripping for me.

That said, I did enjoy reading this, because I love Barker's deconstructed style so much. It's like a cubist picture - glimpses of Ramakrishna from many different perspectives - with a lot of direct addressing of the reader - and short poems/haikus, as you can see here:

In The Cauliflower, Nicola Barker applies her trademark experimental style to describing the real life of Sri Ramakrishna - drawing on a lot of the existing texts about his life, his worship and his character.

I am a big fan of Nicola Barker - but I have to say this is not what I expected. It took me a long time to realise that it was her take on a true story, and I spent quite a lot of the book expecting the story to go in a particular direction - which it never did. In fact there is not that much story - if I was going to summarise the book, it basically said 'there was this guy and he had these crazy effects on the people that knew him'. And I am not at all interested in religious belief or mysticism, so learning about Ramakrishna's life was not that gripping for me.

That said, I did enjoy reading this, because I love Barker's deconstructed style so much. It's like a cubist picture - glimpses of Ramakrishna from many different perspectives - with a lot of direct addressing of the reader - and short poems/haikus, as you can see here:

17wandering_star

9. The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar

A historical novel about the unlikely alliance between a hard-working shipping merchant and a high-class prostitute, in Georgian London. One morning, Jonah Hancock's ship's captain returns to London, not with a ship full of goods to trade, but with a mermaid. Hancock is horrified at the loss of his entire investment, but decides to exhibit the mermaid and becomes a sensation. This briefly takes him into high society, where he meets Angelica Neal, trained by one of the most celebrated brothel owners in London, who has unsuccessfully been trying to go her own way. Seeing Hancock as a prudish joke, she demands that he gets her a mermaid of her own - a request that he takes seriously.

There is plenty in this book that I could have liked. In particular, the descriptions of Georgian London are vivid and tactile, and there is a lot of wit in the writing. But there is a central development in the plot (when Angelica marries Hancock and turns from a lazy spendthrift sensualist into a happy housewife ) which I found vastly unlikely and which undermined the whole book for me - as well as a significant shift of tone in the last act of the story which really seemed to come out of nowhere.

There is an interesting theme about being a person between two worlds - like the mermaid, both Hancock and Angelica don't quite belong where they have ended up. And both of them, individually, are charming characters. But in the end I found this a pretty frustrating read, as it was almost so much better.

Owing to the rain it is unlikely that many birds are abroad, but perhaps a crow has just crept from the rafters of Mr Hancock’s house, and now fans out its bombazine feathers and tips its head to one side to view the world with one pale and peevish eye. This crow, if it spreads its wings, will find them full of the still-damp breeze gusting up from the streets below: hot tar, river mud, the ammoniac reek of the tannery.

A historical novel about the unlikely alliance between a hard-working shipping merchant and a high-class prostitute, in Georgian London. One morning, Jonah Hancock's ship's captain returns to London, not with a ship full of goods to trade, but with a mermaid. Hancock is horrified at the loss of his entire investment, but decides to exhibit the mermaid and becomes a sensation. This briefly takes him into high society, where he meets Angelica Neal, trained by one of the most celebrated brothel owners in London, who has unsuccessfully been trying to go her own way. Seeing Hancock as a prudish joke, she demands that he gets her a mermaid of her own - a request that he takes seriously.

There is plenty in this book that I could have liked. In particular, the descriptions of Georgian London are vivid and tactile, and there is a lot of wit in the writing. But there is a central development in the plot (

There is an interesting theme about being a person between two worlds - like the mermaid, both Hancock and Angelica don't quite belong where they have ended up. And both of them, individually, are charming characters. But in the end I found this a pretty frustrating read, as it was almost so much better.

Owing to the rain it is unlikely that many birds are abroad, but perhaps a crow has just crept from the rafters of Mr Hancock’s house, and now fans out its bombazine feathers and tips its head to one side to view the world with one pale and peevish eye. This crow, if it spreads its wings, will find them full of the still-damp breeze gusting up from the streets below: hot tar, river mud, the ammoniac reek of the tannery.

18wandering_star

10. Gnomon by Nick Harkaway

Well. How on earth to describe this book? We are in a future, mass surveillance society. A woman, Diana Hunter, has died under interrogation - which in this world means the authorities taking a recording of what is going on inside your brain. An investigator, Mielikki Neith, is called in - not to work out why it happened, but to decide whether the interrogation was justified - whether Hunter was in fact a dangerous subversive or whether she was just an old-fashioned person who wanted to avoid surveillance. Her investigation takes the form of viewing the recordings of Hunter's thoughts - but viewing is too simple a word, when you watch a recording like this, it is immersive, as if you are experiencing all these things yourself. And Hunter, in her desire to resist interrogation, has created multiple narratives within herself, all of which Neith viscerally experiences. Neith has to remember who she is, while trying to make sense of the puzzle the multiple narratives create, and work out how on earth this diminutive old woman had the strength of will - or could it be the training? - to project such well-developed alternative narratives while undergoing the procedure of interrogation.

Or to put it more briefly: like a book form of the film Inception.

A hugely ambitious piece of work, and Harkaway probably pulls it off - but it takes a great deal of concentration and persistence from the reader. I think I basically lost track of what was happening about two-thirds of the way through, partly because the book is so long that unless you are reading it on holiday or something, where you can give it several hours a day, it's difficult to connect the details in the different storylines and assemble a coherent picture. (I was also a bit disappointed that we didn't spend more time in the 'now' of the story, the surveillance society, which I found quite clever and interesting - particularly the element that everyone contributes to surveillance by flagging and tagging anything they see which is worthy of note).

The odds, therefore, are negligible that we live in the origin universe, and considerable that we are quite a few steps down the layers of reality. Everything you know, everything you have ever seen or experienced, is probably not what it appears to be. The most alarming notion is that someone – or everyone – you know might be an avatar of someone a level up: they might know that you’re a game piece, that you’re invented and they are real. Perhaps that explains your sense of unfulfilled potential: you truly are incomplete, a semi-autonomous reflection of something vast.

Well. How on earth to describe this book? We are in a future, mass surveillance society. A woman, Diana Hunter, has died under interrogation - which in this world means the authorities taking a recording of what is going on inside your brain. An investigator, Mielikki Neith, is called in - not to work out why it happened, but to decide whether the interrogation was justified - whether Hunter was in fact a dangerous subversive or whether she was just an old-fashioned person who wanted to avoid surveillance. Her investigation takes the form of viewing the recordings of Hunter's thoughts - but viewing is too simple a word, when you watch a recording like this, it is immersive, as if you are experiencing all these things yourself. And Hunter, in her desire to resist interrogation, has created multiple narratives within herself, all of which Neith viscerally experiences. Neith has to remember who she is, while trying to make sense of the puzzle the multiple narratives create, and work out how on earth this diminutive old woman had the strength of will - or could it be the training? - to project such well-developed alternative narratives while undergoing the procedure of interrogation.

Or to put it more briefly: like a book form of the film Inception.

A hugely ambitious piece of work, and Harkaway probably pulls it off - but it takes a great deal of concentration and persistence from the reader. I think I basically lost track of what was happening about two-thirds of the way through, partly because the book is so long that unless you are reading it on holiday or something, where you can give it several hours a day, it's difficult to connect the details in the different storylines and assemble a coherent picture. (I was also a bit disappointed that we didn't spend more time in the 'now' of the story, the surveillance society, which I found quite clever and interesting - particularly the element that everyone contributes to surveillance by flagging and tagging anything they see which is worthy of note).

The odds, therefore, are negligible that we live in the origin universe, and considerable that we are quite a few steps down the layers of reality. Everything you know, everything you have ever seen or experienced, is probably not what it appears to be. The most alarming notion is that someone – or everyone – you know might be an avatar of someone a level up: they might know that you’re a game piece, that you’re invented and they are real. Perhaps that explains your sense of unfulfilled potential: you truly are incomplete, a semi-autonomous reflection of something vast.

19rhian_of_oz

>18 wandering_star: I'm not sure it's exactly accurate to say that I *liked* Gnomon but I'm certainly glad I read it. Lots of interesting ideas.

20valkyrdeath

>16 wandering_star: I just came across mentions of Nicola Barker in Ali Smith's Artful a couple of days ago, and it's got me curious to read something by her, though I'm not quite sure where to start. Looks like it shouldn't be with The Cauliflower. Is there any particular book you'd recommend?

>18 wandering_star: I've been meaning to read Gnomon for a while and your review makes it sound really intriguing. I need to try and get to that one.

>18 wandering_star: I've been meaning to read Gnomon for a while and your review makes it sound really intriguing. I need to try and get to that one.

21wandering_star

>20 valkyrdeath: Good question. I think her best book is Darkmans, but it's definitely not her most accessible - it's 800+ pages and for a lot of the time the reader has no idea what's going on. I remember thinking that reading it was like riding a ghost train with its brake cable cut - hurtling through crazy surroundings with an occasional lighting flash to let you see what's going on. If that doesn't sound appealing, maybe Five Miles from Outer Hope? That's shorter, and a milder version of the style she uses in Darkmans, so it could be a taster.

22auntmarge64

>16 wandering_star: The Cauliflower was certainly not what I expected, either, but I did enjoy it. I've read quite a bit about Ramakrishna so probably could make more sense of it than people who haven't. I think.

23valkyrdeath

>21 wandering_star: Thanks! Darkmans was the one I'd been looking at mainly, and I'm definitely curious, but I'm noting Five Miles from Outer Hope too now and I may be more likely to get to that one first given the length.

24wandering_star

The Skills: From First Job to Dream Job - What Every Woman Needs to Know by Mishal Husain

I skimmed this, which is why I haven't given it a number (it doesn't count towards the year's reading). Mishal Husain is a journalist working for BBC World TV, and the book is pitched as a self-development book for women in the workplace. It is an odd mix - to me, it read like the notes made for a self-help book, which didn't go through the final edit/polish to make it 'self-help'-y - by which I mean, lots of practical takeaways and checklists etc. So you get a lot of statistics and qualitative evidence about some of the challenges for women in the workplace - from the system and from within themselves - and stories about how Husain or people that she has interviewed respond to them. Maybe that's better than a self-help book which is written to be heavily marketed, and which doesn't give credit to the other people whose ideas have helped to form it. But the bigger problem I had is that so little in this book was new to me. Does anyone really not know about women and imposter syndrome, about negative stereotypes which hamper women in the workplace, about the gender pay gap? And the advice didn't contain new insights either. Build resilience by focusing on what went well, not what went badly. Listening is as important as action. And so on. I really wanted to like this book but I have only saved a handful of paragraphs into my notes.

Malala told me she tries to keep the criticism at a distance. ‘I think it’s very healthy to keep yourself away from negative thoughts and comments, but it is reality that they will come your way. If it is fair criticism that does make sense and is justified with reasons, then look at it and check if you are on the right track.’ But she is also determined not to allow any negativity to hold her back. ‘There are people who won’t accept you even if you are an angel. If you get lost in thinking about that, you will lose focus on your key goal and your key aims.’

I skimmed this, which is why I haven't given it a number (it doesn't count towards the year's reading). Mishal Husain is a journalist working for BBC World TV, and the book is pitched as a self-development book for women in the workplace. It is an odd mix - to me, it read like the notes made for a self-help book, which didn't go through the final edit/polish to make it 'self-help'-y - by which I mean, lots of practical takeaways and checklists etc. So you get a lot of statistics and qualitative evidence about some of the challenges for women in the workplace - from the system and from within themselves - and stories about how Husain or people that she has interviewed respond to them. Maybe that's better than a self-help book which is written to be heavily marketed, and which doesn't give credit to the other people whose ideas have helped to form it. But the bigger problem I had is that so little in this book was new to me. Does anyone really not know about women and imposter syndrome, about negative stereotypes which hamper women in the workplace, about the gender pay gap? And the advice didn't contain new insights either. Build resilience by focusing on what went well, not what went badly. Listening is as important as action. And so on. I really wanted to like this book but I have only saved a handful of paragraphs into my notes.

Malala told me she tries to keep the criticism at a distance. ‘I think it’s very healthy to keep yourself away from negative thoughts and comments, but it is reality that they will come your way. If it is fair criticism that does make sense and is justified with reasons, then look at it and check if you are on the right track.’ But she is also determined not to allow any negativity to hold her back. ‘There are people who won’t accept you even if you are an angel. If you get lost in thinking about that, you will lose focus on your key goal and your key aims.’

25wandering_star

11. My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

Ayoola summons me with these words - Korede, I killed him.

I had hoped I would never hear those words again.

That's the opening to this novel, set in Nigeria. Korede, our narrator, is a hardworking and conscientious nurse. She frequently finds herself cleaning up after her sister, who is her polar opposite: beautiful and irresponsible - including in several cases where men close to Ayoola have ended up stabbed to death. She does it because she is the older sister and she has to look after her younger sibling. But then one day she finds Ayoola flirting with the man that she herself is secretly in love with...

Great set-up, but I felt that having got to that point, the book shied away from really making the most of it. It seems to me there are two possible ways of explaining Ayoola's behaviour -either there is a serious trauma in her past which leads her to behave the way she does, or she is killing for the thrill of it . Either one of these could have made a good story but Braithwaite can't commit to either. Similarly with the tension in the set-up between the man she loves and the sister she cares for - this would have made a good story element but is not really developed.

Because of this I found the book basically pretty insubstantial, and disappointing to read.

Ayoola summons me with these words - Korede, I killed him.

I had hoped I would never hear those words again.

That's the opening to this novel, set in Nigeria. Korede, our narrator, is a hardworking and conscientious nurse. She frequently finds herself cleaning up after her sister, who is her polar opposite: beautiful and irresponsible - including in several cases where men close to Ayoola have ended up stabbed to death. She does it because she is the older sister and she has to look after her younger sibling. But then one day she finds Ayoola flirting with the man that she herself is secretly in love with...

Great set-up, but I felt that having got to that point, the book shied away from really making the most of it. It seems to me there are two possible ways of explaining Ayoola's behaviour -

Because of this I found the book basically pretty insubstantial, and disappointing to read.

26wandering_star

12. How to be Famous by Caitlin Moran

The second book in a series (although I didn't realise this when I started it) about Dolly Wilde, a young woman the outlines of whose life have a lot in common with Moran's own (semi-feral childhood in Wolverhampton, moving to London in her mid-teens to work as a music journalist).

It's an entertaining mix of roman-a-clef set in the world of Britpop, and a feminist cautionary tale. For the first part of the book I enjoyed the writing about living in London in those heady years - both the stories which presumably are Moran's own (eg seeing a member of Blur reading a bad review of his own band while sitting in a laundrette) but also the descriptions of what it felt like then:

Britpop songs "…are about the simple brilliance of life in Britain: football in the park, booze in the sun, riding a bike, smoking a fag, fry-ups in a cafe … They have turned everyday life into a jubilee. They have reminded us that life is - above everything else - a party. They have rewired the circuit board. And Britain has fallen in love with this simple promise. To celebrate the everyday glorious. There is a sudden, tremendous hopefulness. All the news is good - the Berlin Wall comes down, Mandela is free, and Eastern Europe has walked out of the Cold War, and into the sunshine. There is a lot of sunshine. When I think back to that time, it feels like it was always sunny … Every week, the radio pumped out more treasure. Every weekend, there was some new, big, anthem to sing."

This then morphs into being about the misogyny of the music industry and of lad culture around that time, via the way that Dolly is treated by a stand-up comedian that she has a one-night stand with. But the book remains funny and uplifting, especially because of Dolly's friendship with an outspoken and outrageous feminist punk who is incredibly cutting, in a very funny way, about the various problems which beset them.

‘This is what will kill Britpop, in the end,’ Suzanne says darkly. ‘An inability to process or express any emotion more complex than, ‘Oi oi, saveloy! Nice tits! Bummer!’

Occasionally patchy but a highly enjoyable and satisfying read.

The second book in a series (although I didn't realise this when I started it) about Dolly Wilde, a young woman the outlines of whose life have a lot in common with Moran's own (semi-feral childhood in Wolverhampton, moving to London in her mid-teens to work as a music journalist).

It's an entertaining mix of roman-a-clef set in the world of Britpop, and a feminist cautionary tale. For the first part of the book I enjoyed the writing about living in London in those heady years - both the stories which presumably are Moran's own (eg seeing a member of Blur reading a bad review of his own band while sitting in a laundrette) but also the descriptions of what it felt like then:

Britpop songs "…are about the simple brilliance of life in Britain: football in the park, booze in the sun, riding a bike, smoking a fag, fry-ups in a cafe … They have turned everyday life into a jubilee. They have reminded us that life is - above everything else - a party. They have rewired the circuit board. And Britain has fallen in love with this simple promise. To celebrate the everyday glorious. There is a sudden, tremendous hopefulness. All the news is good - the Berlin Wall comes down, Mandela is free, and Eastern Europe has walked out of the Cold War, and into the sunshine. There is a lot of sunshine. When I think back to that time, it feels like it was always sunny … Every week, the radio pumped out more treasure. Every weekend, there was some new, big, anthem to sing."

This then morphs into being about the misogyny of the music industry and of lad culture around that time, via the way that Dolly is treated by a stand-up comedian that she has a one-night stand with. But the book remains funny and uplifting, especially because of Dolly's friendship with an outspoken and outrageous feminist punk who is incredibly cutting, in a very funny way, about the various problems which beset them.

‘This is what will kill Britpop, in the end,’ Suzanne says darkly. ‘An inability to process or express any emotion more complex than, ‘Oi oi, saveloy! Nice tits! Bummer!’

Occasionally patchy but a highly enjoyable and satisfying read.

27wandering_star

13. Force of Nature by Jane Harper

Two groups from the same company are on a team-building weekend in a remote wilderness area. One group fails to arrive at the destination on time - and when they do turn up, they are missing one member - and they can't explain exactly what happened while they were trekking through the bush.

The story of the search for the missing person - and the detectives unravelling the story of what happened - is interleaved with episodes from the walk, and we effectively see the tension rising within the team as they realise that they are lost in the impenetrable forest.

‘So we’ve been walking west the whole time?’ Beth said. Since we left the river?’

‘Christ. Yes. I already said.’ Alice didn’t glance up from her phone.

‘Then - ‘ A pause. ‘Sorry. It’s just - if this way is west, then why is the sun setting in the south?’

Every face turned, just in time to see the sun drop another notch below the trees.

This is the second thriller featuring detective Aaron Falk, who is an investigator into financial crimes. In The Dry, he got involved because the crime took place in his home town; in this one, he's involved because the missing person is a key witness in a major case he's working on. They both worked well, but I struggle to see how Harper can find ways to keep linking him into more bloody crimes!

I thought this was a really excellent, gripping thriller with just enough twists. I actually preferred it to The Dry and look forward to reading more of Harper's work.

Two groups from the same company are on a team-building weekend in a remote wilderness area. One group fails to arrive at the destination on time - and when they do turn up, they are missing one member - and they can't explain exactly what happened while they were trekking through the bush.

The story of the search for the missing person - and the detectives unravelling the story of what happened - is interleaved with episodes from the walk, and we effectively see the tension rising within the team as they realise that they are lost in the impenetrable forest.

‘So we’ve been walking west the whole time?’ Beth said. Since we left the river?’

‘Christ. Yes. I already said.’ Alice didn’t glance up from her phone.

‘Then - ‘ A pause. ‘Sorry. It’s just - if this way is west, then why is the sun setting in the south?’

Every face turned, just in time to see the sun drop another notch below the trees.

This is the second thriller featuring detective Aaron Falk, who is an investigator into financial crimes. In The Dry, he got involved because the crime took place in his home town; in this one, he's involved because the missing person is a key witness in a major case he's working on. They both worked well, but I struggle to see how Harper can find ways to keep linking him into more bloody crimes!

I thought this was a really excellent, gripping thriller with just enough twists. I actually preferred it to The Dry and look forward to reading more of Harper's work.

28wandering_star

14. Strange Practice by Vivian Shaw

Dr Greta Helsing (recognise the surname?) runs a medical practice in London catering to monsters - "vampires, were-creatures, mummies, banshees, ghouls, bogeymen, the occasional arthritic barrow-wight." So it is she who first realises that someone - or something - is targeting London's monster community, in a nasty - and horribly effective - way.

This book was tremendous fun! I enjoyed the witty writing, the well-imagined magical/monstrous world, and above all the way that a motley crew of allies worked together to take on the nasties.

There had never been much doubt which subspecialty of medicine she would pursue, once she began her training: treating the differently alive was not only more interesting than catering to the ordinary human population, it was in many ways a great deal more rewarding.

Dr Greta Helsing (recognise the surname?) runs a medical practice in London catering to monsters - "vampires, were-creatures, mummies, banshees, ghouls, bogeymen, the occasional arthritic barrow-wight." So it is she who first realises that someone - or something - is targeting London's monster community, in a nasty - and horribly effective - way.

This book was tremendous fun! I enjoyed the witty writing, the well-imagined magical/monstrous world, and above all the way that a motley crew of allies worked together to take on the nasties.

There had never been much doubt which subspecialty of medicine she would pursue, once she began her training: treating the differently alive was not only more interesting than catering to the ordinary human population, it was in many ways a great deal more rewarding.

29wandering_star

15. Warlight by Michael Ondaatje

In Part One of Warlight we meet two teenage siblings - Nathaniel and Rachel - living in London shortly after World War Two. Their parents have moved to Singapore for a year, sending them to boarding schools which they can't bear - instead they end up living at home, looked after by their lodger, a mysterious man who appears to operate in grey areas of legality - as do the succession of friends and acquaintances that the children come to know. Somehow, in the way of children, Nathaniel (our narrator) doesn't really question where his parents are or what they are doing - until a shocking ending to Part One makes us realise that something else is going on.

In Part Two, Nathaniel is older, and has dedicated much of his life to understanding what was actually happening during those earlier years. He reconstructs much of his mother's early life - but gaps and mysteries remain.

I found it a little hard to get my head around the structure at first, and work out what the book was really about. But all the way through I loved the writing - the atmosphere and that strange half-legal world that Nathaniel was growing up in.

"Warlight" is a description of the little light that was available to find your way around during the blackout - but it's also about the 'light' (or shadow) that the events of wartime cast over ordinary people for generations. And it's a metaphor for the tiny hints and pieces of evidence that Nathaniel can find to help him understand the truth of what happened. The book is about loss and mystery, family secrets, and the role of parents or those acting as parents in shaping a child's life.

A very interesting read.

I used to sit on the top level of a slow-moving bus and peer down at the empty streets. There were parts of the city where you saw no one, only a few children, walking solitary, listless as small ghosts. It was a tie of war ghosts, the grey buildings unlit, even at night, their shattered windows still covered over with black material where glass had been. The city still felt wounded, uncertain of itself. It allowed one to be rule-less. Everything had already happened. Hadn’t it?

In Part One of Warlight we meet two teenage siblings - Nathaniel and Rachel - living in London shortly after World War Two. Their parents have moved to Singapore for a year, sending them to boarding schools which they can't bear - instead they end up living at home, looked after by their lodger, a mysterious man who appears to operate in grey areas of legality - as do the succession of friends and acquaintances that the children come to know. Somehow, in the way of children, Nathaniel (our narrator) doesn't really question where his parents are or what they are doing - until a shocking ending to Part One makes us realise that something else is going on.

In Part Two, Nathaniel is older, and has dedicated much of his life to understanding what was actually happening during those earlier years. He reconstructs much of his mother's early life - but gaps and mysteries remain.

I found it a little hard to get my head around the structure at first, and work out what the book was really about. But all the way through I loved the writing - the atmosphere and that strange half-legal world that Nathaniel was growing up in.

"Warlight" is a description of the little light that was available to find your way around during the blackout - but it's also about the 'light' (or shadow) that the events of wartime cast over ordinary people for generations. And it's a metaphor for the tiny hints and pieces of evidence that Nathaniel can find to help him understand the truth of what happened. The book is about loss and mystery, family secrets, and the role of parents or those acting as parents in shaping a child's life.

A very interesting read.

I used to sit on the top level of a slow-moving bus and peer down at the empty streets. There were parts of the city where you saw no one, only a few children, walking solitary, listless as small ghosts. It was a tie of war ghosts, the grey buildings unlit, even at night, their shattered windows still covered over with black material where glass had been. The city still felt wounded, uncertain of itself. It allowed one to be rule-less. Everything had already happened. Hadn’t it?

30wandering_star

16. The Burial at Thebes by Seamus Heaney

This is the story of Sophocles' Antigone, retold in English verse. I am avoiding the question of whether it's a translation or an adaptation - from what I have been able to find out, it's more of a translation than an adaptation, but Heaney worked from an existing translation rather than the original.

Before the play starts, two brothers died leading opposite sides in a civil war. The new ruler Creon decrees that one will be honoured as the rightful leader, the other will be treated as a traitor and his body will not even be buried. Antigone is the sister of the two dead men, and defies Creon to give her brother the burial rites.

Many years ago I read the Jean Anouilh version of this story, and in my memory at least, that play is one where your sympathies switch between Creon and Antigone. Antigone is fiery in her belief that she is doing what is right, and the personal duty of burying her brother properly is the most important thing. Creon argues that as members of the ruling family, they must do what is right for the state, and follow the law rather than their own preferences.

Because of this I was a bit disappointed by this version, where Creon is clearly not acting out of a desire for a wider good, and Antigone is clearly the sympathetic character.

Chorus: I see the sorrows of this ancient house

Break on the inmates and keep breaking on them

Like foaming wave on wave across a strange.

They stagger to their feet and struggle on

But the gods do not relent, the living fall

Where the dead fell in their day

Generation after generation.

This is the story of Sophocles' Antigone, retold in English verse. I am avoiding the question of whether it's a translation or an adaptation - from what I have been able to find out, it's more of a translation than an adaptation, but Heaney worked from an existing translation rather than the original.

Before the play starts, two brothers died leading opposite sides in a civil war. The new ruler Creon decrees that one will be honoured as the rightful leader, the other will be treated as a traitor and his body will not even be buried. Antigone is the sister of the two dead men, and defies Creon to give her brother the burial rites.

Many years ago I read the Jean Anouilh version of this story, and in my memory at least, that play is one where your sympathies switch between Creon and Antigone. Antigone is fiery in her belief that she is doing what is right, and the personal duty of burying her brother properly is the most important thing. Creon argues that as members of the ruling family, they must do what is right for the state, and follow the law rather than their own preferences.

Because of this I was a bit disappointed by this version, where Creon is clearly not acting out of a desire for a wider good, and Antigone is clearly the sympathetic character.

Chorus: I see the sorrows of this ancient house

Break on the inmates and keep breaking on them

Like foaming wave on wave across a strange.

They stagger to their feet and struggle on

But the gods do not relent, the living fall

Where the dead fell in their day

Generation after generation.

31wandering_star

Maximize Your Potential: Grow Your Expertise, Take Bold Risks & Build an Incredible Career ed. Jocelyn K. Glei

Another skimmed book. It's made up of very short chapters, each by a different person and each with one idea about how to work better - a bit like reading a bunch of Harvard Business Review articles. It is aimed at people working in creative and entrepreneurial fields (which does not describe my workplace!) but I found the parts about how to develop your skills, build your network and challenge yourself reasonably useful.

Trying new things requires a willingness to take risks. However, risk-taking is not binary—you aren’t a risk taker or not a risk taker. You’re likely comfortable taking some types of risks while finding other types uncomfortable. You might not even see the risks that are comfortable for you to take, discounting their riskiness, while you are likely to amplify the risk of things that make you anxious. For example, you might love flying down a ski slope at lightning speed or jumping out of airplanes, and not even view these activities as risky. Or you might love giving public lectures or taking on daunting intellectual challenges. The first group is drawn to physical risks, the second to social risks, and the third to intellectual risks.

Another skimmed book. It's made up of very short chapters, each by a different person and each with one idea about how to work better - a bit like reading a bunch of Harvard Business Review articles. It is aimed at people working in creative and entrepreneurial fields (which does not describe my workplace!) but I found the parts about how to develop your skills, build your network and challenge yourself reasonably useful.

Trying new things requires a willingness to take risks. However, risk-taking is not binary—you aren’t a risk taker or not a risk taker. You’re likely comfortable taking some types of risks while finding other types uncomfortable. You might not even see the risks that are comfortable for you to take, discounting their riskiness, while you are likely to amplify the risk of things that make you anxious. For example, you might love flying down a ski slope at lightning speed or jumping out of airplanes, and not even view these activities as risky. Or you might love giving public lectures or taking on daunting intellectual challenges. The first group is drawn to physical risks, the second to social risks, and the third to intellectual risks.

32wandering_star

17. There There by Tommy Orange

The title of this book comes from the famous quote by Gertrude Stein about Oakland, CA - "There is no there there". The book is set in Oakland, among the 'urban Indian' community - Native Americans who no longer live in traditional ways. And so the title takes on a more poignant meaning - it's not just about a soulless city but about what a Native identity means in that context, away from the land and the traditional ways of living.

At first I thought this book was a collection of short stories, episodes in different people's lives - until I realised that the same narrators came back later in the book, and I could see the way that everyone's story was going to intertwine as they all attended the same powwow.

The characters all identify as Native in some way, but they all find that identity a bit challenged - whether it's because they don't 'look' Native, or they are mixed race and feel that they are out of touch with their traditions. There's also a reference to another 'There There' - a Radiohead song, and in particular the lyric, "Just 'cause you feel it doesn't mean it's there", which could I think refer to the way the characters feel unsettled about their identity.

One character secretly dresses up in someone else's powwow regalia, too small for him. He looks at himself in the mirror and thinks, I am dressed up like an Indian... a fake, a copy, a boy playing dress up. And yet - It's important that he dress like an Indian, dance like an Indian, even if it is an act, even if he feels like a fraud the whole time, because the only way to be Indian in this world is to look and act like an Indian.

As another character listens to a (real) band called 'A Tribe Called Red', he thinks, The problem with Indigenous art in general is that it's stuck in the past. The catch, or the double bind, about the whole thing is this: If it isn't pulling from tradition, how is it Indigenous? And if it is stuck in tradition, in the past, how can it be relevant to other Indigenous people living now, how can it be modern?

This is the challenge that Orange has set himself - to tell a story about what it means to be Native American today, fully living in modern America. Really interesting.

The title of this book comes from the famous quote by Gertrude Stein about Oakland, CA - "There is no there there". The book is set in Oakland, among the 'urban Indian' community - Native Americans who no longer live in traditional ways. And so the title takes on a more poignant meaning - it's not just about a soulless city but about what a Native identity means in that context, away from the land and the traditional ways of living.

At first I thought this book was a collection of short stories, episodes in different people's lives - until I realised that the same narrators came back later in the book, and I could see the way that everyone's story was going to intertwine as they all attended the same powwow.

The characters all identify as Native in some way, but they all find that identity a bit challenged - whether it's because they don't 'look' Native, or they are mixed race and feel that they are out of touch with their traditions. There's also a reference to another 'There There' - a Radiohead song, and in particular the lyric, "Just 'cause you feel it doesn't mean it's there", which could I think refer to the way the characters feel unsettled about their identity.

One character secretly dresses up in someone else's powwow regalia, too small for him. He looks at himself in the mirror and thinks, I am dressed up like an Indian... a fake, a copy, a boy playing dress up. And yet - It's important that he dress like an Indian, dance like an Indian, even if it is an act, even if he feels like a fraud the whole time, because the only way to be Indian in this world is to look and act like an Indian.

As another character listens to a (real) band called 'A Tribe Called Red', he thinks, The problem with Indigenous art in general is that it's stuck in the past. The catch, or the double bind, about the whole thing is this: If it isn't pulling from tradition, how is it Indigenous? And if it is stuck in tradition, in the past, how can it be relevant to other Indigenous people living now, how can it be modern?

This is the challenge that Orange has set himself - to tell a story about what it means to be Native American today, fully living in modern America. Really interesting.

33wandering_star

18. The Poppy War by RF Kuang

Epic fantasy, set in a world which is clearly modelled on China, with some ancient and some modern elements. Our heroine is a young war orphan, whose family of opium smugglers want to marry her off to a middle-aged government official to ensure he'll turn a blind eye to their livelihood. The only way she can think of to escape is to win a place at the country's top academy, Sinegard, which teaches its students everything they need to run the empire.

I really, really enjoyed Part 1 of this book, which is focused on Rin's arrival at and experience of Sinegard. There are six faculties, from martial arts to diplomacy and history - and the baffling 'Lore', whose master behaves like an idiot among the other masters and doesn't show up for his students.

“I’m Lore Master,” Jiang said. “That comes with privileges.” “Privileges like never teaching class?” Jiang lifted his chin and said self-importantly, “I have taught her class the crushing sensation of disappointment and the even more important lesson that they do not matter as much as they think they do.”

It won't surprise anyone who knows anything about traditional Chinese beliefs that the Lore master actually has remarkable skills, but chooses not to use them within the system of the school. This sets up a beautiful tension between having power and deciding what to use it for.

Unfortunately the rest of the book - in which the country descends into war - throws away this tension, stacks the dice on one side of the equation and just becomes about fighting. So overall, I can't recommend it.

Epic fantasy, set in a world which is clearly modelled on China, with some ancient and some modern elements. Our heroine is a young war orphan, whose family of opium smugglers want to marry her off to a middle-aged government official to ensure he'll turn a blind eye to their livelihood. The only way she can think of to escape is to win a place at the country's top academy, Sinegard, which teaches its students everything they need to run the empire.

I really, really enjoyed Part 1 of this book, which is focused on Rin's arrival at and experience of Sinegard. There are six faculties, from martial arts to diplomacy and history - and the baffling 'Lore', whose master behaves like an idiot among the other masters and doesn't show up for his students.

“I’m Lore Master,” Jiang said. “That comes with privileges.” “Privileges like never teaching class?” Jiang lifted his chin and said self-importantly, “I have taught her class the crushing sensation of disappointment and the even more important lesson that they do not matter as much as they think they do.”

It won't surprise anyone who knows anything about traditional Chinese beliefs that the Lore master actually has remarkable skills, but chooses not to use them within the system of the school. This sets up a beautiful tension between having power and deciding what to use it for.

Unfortunately the rest of the book - in which the country descends into war - throws away this tension, stacks the dice on one side of the equation and just becomes about fighting. So overall, I can't recommend it.

34wandering_star

19. My Lot is a Sky: an anthology of poems by Asian women, ed. Melissa Powers and Rena Minegishi

I bought this at an indie bookshop/publishing house in Singapore called Books Actually. They put out a call for commissions for this anthology, so I think that not all of the poets are published elsewhere.

This was one of my favourite bits - from "Not a Dinner Party" by Sherry X Sun (about her parents being sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution):

Exiled to the farthest fold

of the Loess plateau, four fragile hands

born to flourish pens and flick scalpels

hefted rakes that fell

like guillotine-blades on dead river-beds

where the only things that grew

were cheekbones

against sunburnt skin.

I bought this at an indie bookshop/publishing house in Singapore called Books Actually. They put out a call for commissions for this anthology, so I think that not all of the poets are published elsewhere.

This was one of my favourite bits - from "Not a Dinner Party" by Sherry X Sun (about her parents being sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution):

Exiled to the farthest fold

of the Loess plateau, four fragile hands

born to flourish pens and flick scalpels

hefted rakes that fell

like guillotine-blades on dead river-beds

where the only things that grew

were cheekbones

against sunburnt skin.

35wandering_star

20. The Secret History of the Pink Carnation by Lauren Willig

You've heard of the Scarlet Pimpernel, of course. But perhaps you don't know about one of his successors, the Pink Carnation? Eloise, an American graduate student in London, has made it her mission to find out, and one day she stumbles on a fabulous cache of papers...

This is a historical romance, not usually my sort of thing, and I could have happily done without both the romantic parts of the Pink Carnation part, and the really unnecessary frame story (although I think Eloise's story develops through the rest of the series). BUT even so I just found this tremendous fun, a charming romp of historical derring-do and engaging characters. I won't be continuing with the series, but I did enjoy reading this one.

Edouard bowed himself out of the presence of the Bonaparte ladies to chat with some acquaintances, and Amy was about to do likewise, minus the bowing and the acquaintances, when someone cleared his throat behind her. Amy instantly knew just whose throat the sound had issued from. A strong, sun-browned throat she had once seen tantalisingly displayed by an opened collar and loosened cravat. The skin on her arms prickled and her neck ached with the pressure of not turning to look. Oh, blast the man, couldn’t he have even left her a moment to gloat over her good fortune?

You've heard of the Scarlet Pimpernel, of course. But perhaps you don't know about one of his successors, the Pink Carnation? Eloise, an American graduate student in London, has made it her mission to find out, and one day she stumbles on a fabulous cache of papers...

This is a historical romance, not usually my sort of thing, and I could have happily done without both the romantic parts of the Pink Carnation part, and the really unnecessary frame story (although I think Eloise's story develops through the rest of the series). BUT even so I just found this tremendous fun, a charming romp of historical derring-do and engaging characters. I won't be continuing with the series, but I did enjoy reading this one.

Edouard bowed himself out of the presence of the Bonaparte ladies to chat with some acquaintances, and Amy was about to do likewise, minus the bowing and the acquaintances, when someone cleared his throat behind her. Amy instantly knew just whose throat the sound had issued from. A strong, sun-browned throat she had once seen tantalisingly displayed by an opened collar and loosened cravat. The skin on her arms prickled and her neck ached with the pressure of not turning to look. Oh, blast the man, couldn’t he have even left her a moment to gloat over her good fortune?

36wandering_star

21. An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

A couple of years into a young couple's marriage, one of them is wrongfully convicted and sent to prison for 12 years. I don't want to say too much about what happens after that, except that this book shows you the same story through several different eyes, making you ache for the plight the couple and those around them find themselves in, and showing you how people might behave in such an extreme situation. Beautifully written, and moving.

'It's not about fault,' I said. But of course there was that nagging voice insisting that being with Celestial was a crime like identity theft or tomb raiding. Go get your own woman, it scolded me in Roy's voice. Other times it was like my father reminding me that 'all you have is your good name', which should have been a joke coming from him. But alongside all the clutter in my head was my grandmother's advice: 'What's for you is for you. Extend your hand and claim your blessing.' I never told Celestial about the voices, but I'm sure she hosted a choir of her own.