Finding the pen-name's author, Edward Oxford: Sonnet XLVIII

DiscussionsThe Globe: Shakespeare, his Contemporaries, and Context

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

Ce sujet est actuellement indiqué comme "en sommeil"—le dernier message date de plus de 90 jours. Vous pouvez le réveiller en postant une réponse.

1proximity1

Edited: May 30, 2018 11:05am

Revised October 30, 2018

____________________________________________________

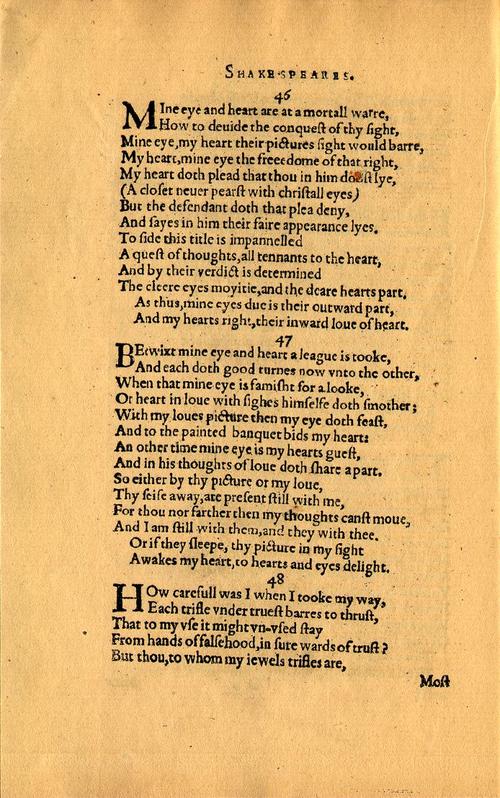

HOw carefull was I when I tooke my way,

Each trifle vnder truest barres to thrust, ...

___________________________________________

__________________________________

Oxford's plays--not only under the pen-name "Shakespeare" but others as well--show us his major preoccupations in the themes which again and again run through his work:

Noble life's duties, the importance of honor, of truth and how these were all-important to one's ambitions for a name that lived on among posterity--thus, life's mortal span, ending in death runs concurrently with these other themes.

So, when such an author speaks to us of things kept is security against theft or loss, so that they may be used and that they may endure, we ought to pay attention.

Here is Oxford speaking to us about things which he holds dear and how he has taken pains to ensure their safe-keeping:

The possibility that these lines carry double meanings which include cryptic allusions to one or more actual places in which he'd prepared the long-term safe-keeping of his papers should not be dismissed outright.

His sonnet here attests to a cognizance of the things he prizes, their risk to theft by others or loss and how, in the very opening line, he tells us he has taken care, when he "tooke his way" to thrust each trifle "Under truest barres".

We know that he was never unmindful of the cognate feature of his own name "Vere," and the then daily-used Latin tongue, in which its varied forms denoted "true", "truth".

Thus, "truest barres" can itself carry multiple associations and imports. Truest bars can refer to actual or metaphorical bars which relate to his family, Vere, property. It may thus have a reference to bars located at what then existed as the generations-old De Vere family estate Earls Colne Priory grounds, on which the family had an estate and mansion--renovated over the course of centuries--though there is not any evidence of which I am aware that Edward spent significant amounts of time there.

Oxford lived in several places in or near London's or Westminster's borroughs. Late in life he lived at what was called "King's Place"* in Bishopsgate Ward along or near Bishopsgate Street and within easy walking distance of St. Helen's church in Bishopsgate and St. Mary Axe. (Find all these locales on the Agas Map of Early Modern London using the map's Key to locations By Category and selecting "Sites" (upper right corner of the page) for a listing )

So it may be a reference to one of these places of residence. It may refer to a place held by another relative of Oxford or a close and highly-trusted friend. It may refer, unfortunately, to a site now lost--some place within Whitehall Palace or Richmond Palace. "Barres" might refer to a natural locale, a durable and recognizable landform, at which these things were buried in chests.

Whatever is referred to in the way of trifles thrust under truest bars, they were evidently things which were not only physical articles but "moveable" physical valuables or else they could not have been thrust under bars for safekeeping. And, equally obvious, they are put there in order

"That to my use it might un-usèd stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!"

"wards of trust" can also carry several senses. But since we were first alerted by the oddity "HOw" (carefull was I ... careful to what? to thrust under truest barres (for safety) "each trifle" --which are also, as the author tells us, his "jewels"-- "in sure wards of trust) Thus, within four lines we have "HOw" and sure wards of trust," suggesting, I think, a reference to someone-- someone in the Howard family (chart of the family line, part II).

A "ward" is also a part of London--Bishopsgate ward, for example; a "ward" of trust might also refer to a youth placed under the care and supervision of a third party-- as was once Edward himself when a ward of Elizabeth I's court--and as was Edward's youthful peer, Edward Manners, the Third Earl of Rutland, one year older than Oxford, both of them under the authority of William Cecil, later Edward's father-in-law, Lord Burghley. Though this "ward" must have been "sure" and, thus, out of reach or control of those who Oxford has in mind when he refers to "stay" "vn-usèd" "From hands of falsehood."

It would seem reasonable to suppose, then, that the place--"in sure wards of trust" is one which is first, and most likely, unknown to the people who bear hands of falsehood and, if not, then, secondly, beyond these people's capacity to access for some reason.

"HOw careful was I"

Frances Howard, later the Countess of Surrey, was born in 1516, the daughter of John de Vere, the Fifteenth Earl of Oxford (1482 – 21 March 1540) and Elizabeth Trussell (1496 – before July 1527). Together they had six other children, John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, Aubrey de Vere, Robert de Vere, Geoffrey de Vere, Elizabeth de Vere, Anne de Vere. Thus, Frances de Vere Frances was sister to the 16th Earl of Oxford. She married a Howard, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in 1532. And together they had five children: Thomas (4th Duke of Norfolk), Jane (Countess of Westmoreland), Margaret (Baroness Scrope of Bolton, the second wife of Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton), (Margaret was seven years' Edward's senior) Henry (1st Earl of Northampton) and Catherine (1538-1596) (Baroness Berkeley) was twelve years senior to Edward.

The House of Howard was one of England's most prestigious, with many high ranking nobles holding important offices of state.

In letters, Oxford's medium of communication, "truest barres" suggests the letter"H" since one or more "H"s strung together resembles bars:

HHHHHHHHHH

HHHHHHHHHH

and, stretching slightly the possibilities, there is also "W" as bars.

Oxford had close and varied kinds of association with Henry Carey, the First Baron (and so, Lord) Hunsdon, often referred to as "Henry Hunsdon."

Hunsdon was a generation older than Oxford and quite politically influential

as well as very important in the world of theater; both Hunsdon and, as I believe was the case, Oxford, were at various times in sexual affairs with the much younger Emilia Bassano of the Venetian musical family-- already immigrants to London for generations by the time that Emilia was born (in Bishopsgate ward) in 1569. As others among Oxfordians do, I take her to have been the "Dark lady" of these sonnets and Hunsdon to have been one of her lovers in addition to Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, four years younger than Emilia. Thus, Emilia had affairs with these three who knew each other well: Carey (Hunsdon) , Wriothesley (Southampton) and (Oxford) Edward de Vere.

Numerous members of the Bassano family lived in Bishopsgate ward--Emilia's father and her numerous uncles and cousins. Oxford also lived in the neighborhood--and there is some indicaion that at one time Emilia had a residence within only several doors of Oxford's own. But, unless Oxford had become a frequent visitor to the home of some of the elder Bassanos--a distinct possibility as these were men his own age and older-- he was almost certainly to have first met Emilia in her childhood when her family elders would have brought her to musical practice and performances at court.

________________________

* "Kings Place," (16th C.) in the Bishopsgate / Shoreditch area of greater London, not to be confused with the modern development by that name located near King's Cross / St. Pancras rail and London Underground stations.

Revised October 30, 2018

____________________________________________________

HOw carefull was I when I tooke my way,

Each trifle vnder truest barres to thrust, ...

___________________________________________

__________________________________

Oxford's plays--not only under the pen-name "Shakespeare" but others as well--show us his major preoccupations in the themes which again and again run through his work:

Noble life's duties, the importance of honor, of truth and how these were all-important to one's ambitions for a name that lived on among posterity--thus, life's mortal span, ending in death runs concurrently with these other themes.

So, when such an author speaks to us of things kept is security against theft or loss, so that they may be used and that they may endure, we ought to pay attention.

Here is Oxford speaking to us about things which he holds dear and how he has taken pains to ensure their safe-keeping:

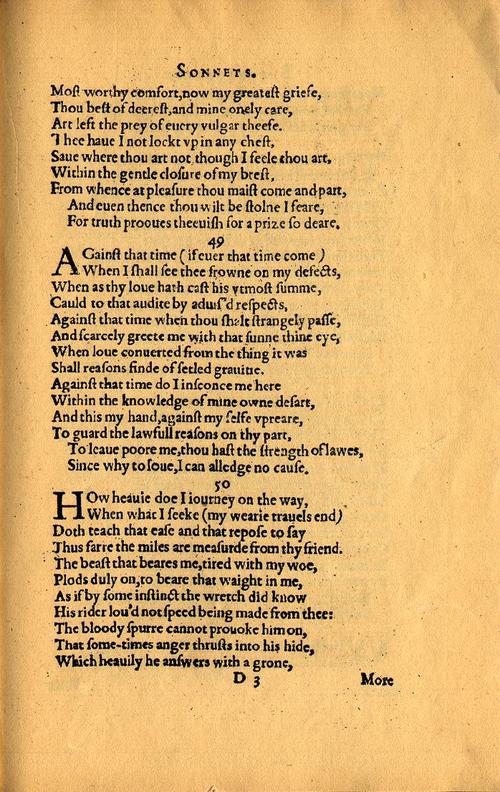

HOw careful was I, when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unusèd stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou, best of dearest and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not lock’d up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art,

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part;

And even thence thou wilt be stol’n, I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

The possibility that these lines carry double meanings which include cryptic allusions to one or more actual places in which he'd prepared the long-term safe-keeping of his papers should not be dismissed outright.

His sonnet here attests to a cognizance of the things he prizes, their risk to theft by others or loss and how, in the very opening line, he tells us he has taken care, when he "tooke his way" to thrust each trifle "Under truest barres".

We know that he was never unmindful of the cognate feature of his own name "Vere," and the then daily-used Latin tongue, in which its varied forms denoted "true", "truth".

Thus, "truest barres" can itself carry multiple associations and imports. Truest bars can refer to actual or metaphorical bars which relate to his family, Vere, property. It may thus have a reference to bars located at what then existed as the generations-old De Vere family estate Earls Colne Priory grounds, on which the family had an estate and mansion--renovated over the course of centuries--though there is not any evidence of which I am aware that Edward spent significant amounts of time there.

Oxford lived in several places in or near London's or Westminster's borroughs. Late in life he lived at what was called "King's Place"* in Bishopsgate Ward along or near Bishopsgate Street and within easy walking distance of St. Helen's church in Bishopsgate and St. Mary Axe. (Find all these locales on the Agas Map of Early Modern London using the map's Key to locations By Category and selecting "Sites" (upper right corner of the page) for a listing )

So it may be a reference to one of these places of residence. It may refer to a place held by another relative of Oxford or a close and highly-trusted friend. It may refer, unfortunately, to a site now lost--some place within Whitehall Palace or Richmond Palace. "Barres" might refer to a natural locale, a durable and recognizable landform, at which these things were buried in chests.

"Bars" in Oxford's day also referred—especially in London and its environs—to "limits", particularly the physical limits of a geographical entity. The "Bars" of London were physical barriers erected to demarcate the boundaries of London (just beyond the old City's walls) along the major lanes of entry to the City—accessible through "gates", thus, "Bishopsgate", "Aldgate", "Moorgate", "Ludgate" were indications of physical gates into the City through its walls.

Thus, to place something under the security of "truest bars" suggests that it is secure inside a delimited locale—physical or conceptual in character or nature—and, so, "out of reach" to people or things which do or might pose a threat to the thing's safety.

(from Chapter I : “The London That Grew Up” | pp. 1 – 2 )

___________________________________________________

“London west of the Bars is the London that grew up. … The London that blossomed from a walled city to a royal metropolis set with the palaces of kings, the seat of law and the centres of enlightenment, military power and culture. …

It is also, incidentally, the vindication and triumph of suburbia.

“That is what ‘Beyond the Bars’ means—suburbia. The Bars represent the extra-mural limits of the City’s laws. Beyond them the rule and protection of the City ceased. Even that limit was a concession. Normally, the law stopped at the walls and any buildings beyond were dubbed with too easy contempt ’suburbs,’ and were mainly occupied by non-freeman.* But in time it was felt expedient to extend legal cover to the approaches without (i.e. ‘outside’) the gates; possibly to regulate and protect the clusters of buildings that grew up on the no-man’s-land outside the walls as a convenient point for collecting tolls; or possibly as an outpost to hold an enemy while refugee crowds got safely behind the walls and the defences within had time to rally to their posts. …

“For these reasons the early Londoners stretched chains across the trackways” (a lane, road, street, throughfare in which physical bars (uprights) were erected as barriers to unimpeded passage) “and later, at Temple Bar, a wooden guardhouse with a stout gate, but not until (Christopher) Wren’s time a structure of stone. Thus the citizens barred the way to all making for the City, exacting tolls for the passage of vehicles not belonging to freemen; kept an eye open for strangers, rogues and serfs, the latter being able to gain their freedom if they could reside within the walls of a town for a year and a day. … Temple Bar, after Whitechapel (on the main eastern approach to the City), was the busiest as well as the most important of these, for it had royal rights of checking even kings, no less than those Londoners who had built their pleasant suburban villas beyond the Roman cemeteries of Fleet Street on the Cliffside above the Thames, as did those who left town at night to sleep in the fresh air of the fields about Holborn.”

_________________________________________________________

Douglas Newton, London West of the Bars, (1951), London, Robert Hale, Ltd., publishers

___________________________________

* See the Agas Map of Early Modern London and Aldgate Bars , Holborn Bars and Temple Bar .

*See also the term ”Liberties” .

Whatever is referred to in the way of trifles thrust under truest bars, they were evidently things which were not only physical articles but "moveable" physical valuables or else they could not have been thrust under bars for safekeeping. And, equally obvious, they are put there in order

"That to my use it might un-usèd stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!"

"wards of trust" can also carry several senses. But since we were first alerted by the oddity "HOw" (carefull was I ... careful to what? to thrust under truest barres (for safety) "each trifle" --which are also, as the author tells us, his "jewels"-- "in sure wards of trust) Thus, within four lines we have "HOw" and sure wards of trust," suggesting, I think, a reference to someone-- someone in the Howard family (chart of the family line, part II).

A "ward" is also a part of London--Bishopsgate ward, for example; a "ward" of trust might also refer to a youth placed under the care and supervision of a third party-- as was once Edward himself when a ward of Elizabeth I's court--and as was Edward's youthful peer, Edward Manners, the Third Earl of Rutland, one year older than Oxford, both of them under the authority of William Cecil, later Edward's father-in-law, Lord Burghley. Though this "ward" must have been "sure" and, thus, out of reach or control of those who Oxford has in mind when he refers to "stay" "vn-usèd" "From hands of falsehood."

It would seem reasonable to suppose, then, that the place--"in sure wards of trust" is one which is first, and most likely, unknown to the people who bear hands of falsehood and, if not, then, secondly, beyond these people's capacity to access for some reason.

"HOw careful was I"

Frances Howard, later the Countess of Surrey, was born in 1516, the daughter of John de Vere, the Fifteenth Earl of Oxford (1482 – 21 March 1540) and Elizabeth Trussell (1496 – before July 1527). Together they had six other children, John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, Aubrey de Vere, Robert de Vere, Geoffrey de Vere, Elizabeth de Vere, Anne de Vere. Thus, Frances de Vere Frances was sister to the 16th Earl of Oxford. She married a Howard, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in 1532. And together they had five children: Thomas (4th Duke of Norfolk), Jane (Countess of Westmoreland), Margaret (Baroness Scrope of Bolton, the second wife of Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton), (Margaret was seven years' Edward's senior) Henry (1st Earl of Northampton) and Catherine (1538-1596) (Baroness Berkeley) was twelve years senior to Edward.

The House of Howard was one of England's most prestigious, with many high ranking nobles holding important offices of state.

In letters, Oxford's medium of communication, "truest barres" suggests the letter"H" since one or more "H"s strung together resembles bars:

HHHHHHHHHH

HHHHHHHHHH

and, stretching slightly the possibilities, there is also "W" as bars.

Oxford had close and varied kinds of association with Henry Carey, the First Baron (and so, Lord) Hunsdon, often referred to as "Henry Hunsdon."

Hunsdon was a generation older than Oxford and quite politically influential

(from Wikipedia's profile page on Hunsdon:

" twice ... Member of Parliament, representing Buckingham during 1547–1550—entering when he was 21—and 1554–1555. "

" knighted in November 1558 and created Baron by his first cousin Elizabeth I of England on 13 January 1559."

"appointed ... Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners in 1564, a position making him effectively her personal bodyguard for four years."

"appointed Lieutenant General of the forces loyal to the Queen" during the Northern Rebellion (November 1569 - February 1570)

"named Privy Counsellor in 1577."

..."1581 ... appointed Captain-General of the forces responsible for the safety of English borders"

"... appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Household in ... 1585 and ... hold this position until his death."

... "Lord Chamberlain Lieutenant, Principal Captain and Governor of the army "for the defence and surety of our own Royal Person".

" patron of ("Shakespeare's") theatre company, known as the Lord Chamberlain's Men

as well as very important in the world of theater; both Hunsdon and, as I believe was the case, Oxford, were at various times in sexual affairs with the much younger Emilia Bassano of the Venetian musical family-- already immigrants to London for generations by the time that Emilia was born (in Bishopsgate ward) in 1569. As others among Oxfordians do, I take her to have been the "Dark lady" of these sonnets and Hunsdon to have been one of her lovers in addition to Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, four years younger than Emilia. Thus, Emilia had affairs with these three who knew each other well: Carey (Hunsdon) , Wriothesley (Southampton) and (Oxford) Edward de Vere.

Numerous members of the Bassano family lived in Bishopsgate ward--Emilia's father and her numerous uncles and cousins. Oxford also lived in the neighborhood--and there is some indicaion that at one time Emilia had a residence within only several doors of Oxford's own. But, unless Oxford had become a frequent visitor to the home of some of the elder Bassanos--a distinct possibility as these were men his own age and older-- he was almost certainly to have first met Emilia in her childhood when her family elders would have brought her to musical practice and performances at court.

________________________

* "Kings Place," (16th C.) in the Bishopsgate / Shoreditch area of greater London, not to be confused with the modern development by that name located near King's Cross / St. Pancras rail and London Underground stations.