SassyLassy on the Other Side

Ceci est la suite du sujet SassyLassy and the Great Outdoors + ... More 19th Century.

DiscussionsClub Read 2017

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

Ce sujet est actuellement indiqué comme "en sommeil"—le dernier message date de plus de 90 jours. Vous pouvez le réveiller en postant une réponse.

2SassyLassy

Why would anyone start a new thread with less than a week left in the year? Well, this is more for myself as my year was truly two different worlds and I wanted to make that distinction with my reading. Here's hoping I get through it all.

3SassyLassy

The Time in Between seemed like an apt title for a book to read on my long drive from my former home to my new one.

22. The Time in Between by Maria Duenas translated from the Spanish by Daniel Hahn 2011

first published as El tiempo entre costuras in 2009

finished reading July 2017

There are many betweens in this novel by Maria Duenas. The strictly literal one is that time between the start of the Spanish Civil War and the end of World War II. Sira Quiroga, the main protagonist, is first seen in the awkward time between girlhood and adulthood, not really an adolescence, for this is wartime and there is no time for that; people grow up quickly in such circumstances. Sira moved between Spain and Spanish Morocco and back again as the political situation dictated. Later in the novel, she moved between roles, between the light and the shadows.

This is an old fashioned kind of meaty novel. It is the kind about which people used to say "You could give it to your grandmother". That is not to slight it in any way, just to set it in genre. The straightforward narrative has lots of action and colourful characters. The worst things that happen are generally offstage, although there is no denying the war all around. Duenas has skilfully interwoven characters from real life like Juan Biegbeder, Minister of Foreign Affairs for Franco from 1939-40, and his lover the Englishwoman Rosalind Fox, suspected by some of being an English spy, and by others of being a German sympathizer. There's a lot of domestic life, which perhaps gives the novel that feel of older books, the so called "ladies' fiction". Sira is a dressmaker, which is critical to the plot, and there is lots of detail here about the time and its fashions.

Maria Duenas is a professor at the University of Murcia. This is her first novel, but I notice there are others now published. This was a book I would have been highly unlikely to read under other circumstances, but it worked very well at the time, and I enjoyed it.

22. The Time in Between by Maria Duenas translated from the Spanish by Daniel Hahn 2011

first published as El tiempo entre costuras in 2009

finished reading July 2017

There are many betweens in this novel by Maria Duenas. The strictly literal one is that time between the start of the Spanish Civil War and the end of World War II. Sira Quiroga, the main protagonist, is first seen in the awkward time between girlhood and adulthood, not really an adolescence, for this is wartime and there is no time for that; people grow up quickly in such circumstances. Sira moved between Spain and Spanish Morocco and back again as the political situation dictated. Later in the novel, she moved between roles, between the light and the shadows.

This is an old fashioned kind of meaty novel. It is the kind about which people used to say "You could give it to your grandmother". That is not to slight it in any way, just to set it in genre. The straightforward narrative has lots of action and colourful characters. The worst things that happen are generally offstage, although there is no denying the war all around. Duenas has skilfully interwoven characters from real life like Juan Biegbeder, Minister of Foreign Affairs for Franco from 1939-40, and his lover the Englishwoman Rosalind Fox, suspected by some of being an English spy, and by others of being a German sympathizer. There's a lot of domestic life, which perhaps gives the novel that feel of older books, the so called "ladies' fiction". Sira is a dressmaker, which is critical to the plot, and there is lots of detail here about the time and its fashions.

Maria Duenas is a professor at the University of Murcia. This is her first novel, but I notice there are others now published. This was a book I would have been highly unlikely to read under other circumstances, but it worked very well at the time, and I enjoyed it.

4SassyLassy

This next book was read for Reading Globally's third quarter theme: Minority Language Writers in their own Countries.

23. A Broken Mirror by Mercè Rodoreda translated from the Catalan by Josep Miquel Sobrer 2006

first published as Mirall trencat in 1962

finished reading July 2017

A Broken Mirror is another novel with an old fashioned feel, but this one is more one of Balzac, for Mercè Rodoreda is a family chronicler on that level.

Right from the first chapter, the reader knows that Teresa Goday is a force to be reckoned with. She is first seen on an expedition with her wealthy much older husband, Senyor Nicolau Rovira. He had recently bought her a very expensive brooch to mark their six month anniversary. Teresa had disdained it, and so here they were, back at the jeweller's to buy another piece. The jeweller mentally reviewed their story:

This time Rovira bought the most elaborate piece in the shop, to Teresa's delight.

In that first chapter we learn much about Teresa, as she carries out a complex scheme with the jeweller to get money to pay for the board of her illegitimate son, deceiving her husband, who knew nothing about the child, still further, in a successful twist on having your cake and eating it too.

Over the years, Teresa will become the highly respected matriarch of a wealthy Barcelona family. The story is told in fragments, from multiple characters' points of view. Like the shards of the mirror the old servant breaks, the fragments can never be assembled to form a complete whole. Each piece, each chapter, reveals something.

Rodoreda, a Catalan nationalist, left her Barcelona home early in 1939 as Franco's troops closed in on the city. She did not return to Catalonia until 1979, four years before her death. A Broken Mirror, written in exile with an exile's love for a home that cannot be, like the home Teresa will try to make, but that will splinter with the war, is also a picture of a fragmented and broken Catalan society.

This is an author I will look for again.

23. A Broken Mirror by Mercè Rodoreda translated from the Catalan by Josep Miquel Sobrer 2006

first published as Mirall trencat in 1962

finished reading July 2017

A Broken Mirror is another novel with an old fashioned feel, but this one is more one of Balzac, for Mercè Rodoreda is a family chronicler on that level.

Right from the first chapter, the reader knows that Teresa Goday is a force to be reckoned with. She is first seen on an expedition with her wealthy much older husband, Senyor Nicolau Rovira. He had recently bought her a very expensive brooch to mark their six month anniversary. Teresa had disdained it, and so here they were, back at the jeweller's to buy another piece. The jeweller mentally reviewed their story:

Senyor Rovira, in his old age, had married a girl of low origins; who knew what those seemingly innocent eyes and that great beauty might hide? 'These marriages work sometimes' he thought, 'but it's better not to chance it'.

This time Rovira bought the most elaborate piece in the shop, to Teresa's delight.

In that first chapter we learn much about Teresa, as she carries out a complex scheme with the jeweller to get money to pay for the board of her illegitimate son, deceiving her husband, who knew nothing about the child, still further, in a successful twist on having your cake and eating it too.

Over the years, Teresa will become the highly respected matriarch of a wealthy Barcelona family. The story is told in fragments, from multiple characters' points of view. Like the shards of the mirror the old servant breaks, the fragments can never be assembled to form a complete whole. Each piece, each chapter, reveals something.

Rodoreda, a Catalan nationalist, left her Barcelona home early in 1939 as Franco's troops closed in on the city. She did not return to Catalonia until 1979, four years before her death. A Broken Mirror, written in exile with an exile's love for a home that cannot be, like the home Teresa will try to make, but that will splinter with the war, is also a picture of a fragmented and broken Catalan society.

This is an author I will look for again.

5mabith

There's a TV show adaptation of The Time in Between that I've seen a bit of, but had no idea it was based on a book. Unfortunately Netflix has screwy subtitles so it would miss entire lines at times so I stopped watching (it looked like a great show, and I knew enough Spanish to know there were gaps but not enough to feel confident in understanding them).

I'll definitely be looking A Broken Mirror too.

I'll definitely be looking A Broken Mirror too.

6SassyLassy

>5 mabith: Thanks for mentioning the Netflix adaptation. I kept thinking as I read that it would make a great movie.

7SassyLassy

24. The Long Drop by Denise Mina

first published 2017

finished reading July 2017

Three men sit together in a Glasgow bar in early December, 1957. There's nothing unusual about that, but the atmosphere around them is tense, expectant, for the others in the room recognize at least two of them, in different combinations, and know something is up. There's Laurence Dowdall, the best known, for he is Glasgow's best criminal lawyer, the one everyone wants. There's William Watt, a wealthy but unpolished businessman, whom Dowdall has just managed to get released from jail, where Watt had been on now dropped charges of murdering his wife, sister-in-law, and daughter. The third man was Peter Manuel, just out of prison where he had served a sentence for rape. They are here now because Manuel claimed he had information on the gun used in the murders.

The Long Drop is based on a true story. In later court proceedings, much will hinge on the twelve hours Watt and Manuel spent drinking together after Dowdall wisely left them to it. It is these twelve hours which Mina brings to life in her novel. She has taken court documents, newspaper reports, and other documentation, and skilfully turned them into a taut narrative that keeps the reader following through to the end, despite knowing the outcome.

Most of all though, this book feels like an ode to Glasgow. Not today's post European culture capital Glasgow, but the gritty city of old, still within living memory for some. As Mina tells it

Above the roofs every chimney belches black smoke. Rain drags smut down over the city like a mourning mantilla. Soon a Clean Air Act will outlaw coal-burning in town. Five square miles of the Victorian city will be ruled unfit for human habitation and torn down, redeveloped in concrete and glass and steel. The population will be moved to the periphery, thinned to a quarter of its current density. One hundred and thirty thousand homes will be demolished in the biggest urban redevelopment project in post-war Europe. Later, the black, bedraggled survivors of this architectural cull will be sandblasted, their hard skin scoured off to reveal glittering yellow and burgundy sandstone. The exposed stone is porous though, it sucks in rain and splits when it freezes in the winter.

But this story is before all that. This story happens in the old boom city, crowded, wild west, chaotic. This city is commerce unfettered. It centres around the docks and the river, and it is all function. It dresses like the Irishwomen: head to toe in black, hair covered, eyes down.

Mina herself recognizes her nostalgia for a Glasgow she never knew, saying in her acknowledgements ...writing a book is like living a parallel life part time. There were times when I could stand and feel the blackened old city growing up around me.

This snapshot is as good as any for a glimpse into how parts of that Glasgow worked.

8avaland

I don't know if this was the Mina I attempted earlier this year and just could not get into. It was hardcover published this year, so it's possible. There was something about the voice.... (granted, I was in a lot of pain this year and my tolerance level was low....) I have really enjoyed her other work.

9dchaikin

Enjoyed these three terrific reviews. Had no idea about that aspect of Glasgow’s history. I’m going to keep a Broken Mirror in mind as that review captures my imagination a bit.

10SassyLassy

>8 avaland: I remember you mentioning one and wondered if this was it. I did enjoy your Glasgow Kiss review with your mention of other writers and "people dying all over Scotland"

>8 avaland: and >9 dchaikin: Glasgow is one of those cities that people either seem to love or hate; there are very few in between. It is probably my favourite city, right from the time the train starts to pull into whichever station you are using. There is an energy there that just seems to reverberate through those old streets. Montreal is another favourite for many of the same reasons.

>8 avaland: and >9 dchaikin: Glasgow is one of those cities that people either seem to love or hate; there are very few in between. It is probably my favourite city, right from the time the train starts to pull into whichever station you are using. There is an energy there that just seems to reverberate through those old streets. Montreal is another favourite for many of the same reasons.

11SassyLassy

This is one of those books I first heard of through LT. I bought it for a Reading Globally quarter on Non European French Speaking Countries way back in 2013 and didn't get it read then: http://www.librarything.com/topic/155414, but am very happy to have finally read it.

25. Proud Beggars by Albert Cossery translated from the French by Thomas Cushing 1981 with revisions by Alyson Waters 2011

first published as Mendiants et orqueilleux in 1955

finished reading July 30, 2017

The idea of proud beggars may seem somewhat of a paradox. The pride Albert Cossery's beggars have, however, is pride in its best sense; a certain dignity and carriage from knowing oneself, from achieving a state where the world of possessions becomes unnecessary, and from being able to determine your own course. All this sounds somewhat serious, but Cossery's book is full of humour, irony, and gentle mockery of the powers that be. It is also a wonderful look at the underbelly of Cairo.

Gohar, a former professor, had renounced all possessions. He slept on a bed of newspapers in a room furnished only with a chair and overturned box. "Objects concealed hidden germs of misery - the worst kind of all, unconscious misery... Gohar found an elusive beauty in the poverty of this room, where he could breathe freely and optimistically... Only people with their endless follies had the power to amuse him." Gohar's dream was to move to Syria, for he was a hashish addict, and believed that hash was free there, anytime, anywhere. To support his habit, he did the books for a brothel.

Gohar's supplier was Yeghen, a mystical poet, so ugly he never had a chance whenever he was brought before the magistrates. His ugliness convicted him. These prison terms though

Then there was El Kordi, a dilettante revolutionary working as a minor government clerk. His dream was to free Arnaba from the brothel where she worked before she died of consumption. Unfortunately for Arnaba, his only idea of how to do this was to commit suicide, something he simply could not bring himself to do. It didn't matter much to Arnaba, for very early in the book she is murdered, a crime Cossery called "a blunder, a minor incident".

The crime though brings in Nour El Dine, the police inspector. This was a man who longed for a criminal as clever as he thought himself to be. Convinced that one of Gohar, Yeghen, or El Kordi was the murderer, he tried to engage each in turn on a personal level. However, he soon discovered "these disreputable intellectuals were forever breaking down all sense of authority in him". They had no idea of his world of institutions and government.

It is this play off between his world and theirs, the questions it raises in his policeman's mind, that are the substance and delight of this book.

________________

Albert Cossery (1913-2008) was born in Cairo and educated in French language schools. In 1945 he settled permanently in Paris, winning the Grand Prix de la francophonie de l'Académie française in 1990. It is this blend of Egyptian and French backgrounds which makes his writing so individual.

25. Proud Beggars by Albert Cossery translated from the French by Thomas Cushing 1981 with revisions by Alyson Waters 2011

first published as Mendiants et orqueilleux in 1955

finished reading July 30, 2017

The idea of proud beggars may seem somewhat of a paradox. The pride Albert Cossery's beggars have, however, is pride in its best sense; a certain dignity and carriage from knowing oneself, from achieving a state where the world of possessions becomes unnecessary, and from being able to determine your own course. All this sounds somewhat serious, but Cossery's book is full of humour, irony, and gentle mockery of the powers that be. It is also a wonderful look at the underbelly of Cairo.

Gohar, a former professor, had renounced all possessions. He slept on a bed of newspapers in a room furnished only with a chair and overturned box. "Objects concealed hidden germs of misery - the worst kind of all, unconscious misery... Gohar found an elusive beauty in the poverty of this room, where he could breathe freely and optimistically... Only people with their endless follies had the power to amuse him." Gohar's dream was to move to Syria, for he was a hashish addict, and believed that hash was free there, anytime, anywhere. To support his habit, he did the books for a brothel.

Gohar's supplier was Yeghen, a mystical poet, so ugly he never had a chance whenever he was brought before the magistrates. His ugliness convicted him. These prison terms though

... allowed him a certain freedom of movement... As soon as he arrived, the odious building, constructed to dishearten men, resounded with tumultuous joy. His jokes and humorous ideas delighted his companions, otherwise inclined to the sadness inherent in their condition. ... Freedom was an abstract notion and a bourgeois prejudice. You could never make Yeghen believe he wasn't free.

Then there was El Kordi, a dilettante revolutionary working as a minor government clerk. His dream was to free Arnaba from the brothel where she worked before she died of consumption. Unfortunately for Arnaba, his only idea of how to do this was to commit suicide, something he simply could not bring himself to do. It didn't matter much to Arnaba, for very early in the book she is murdered, a crime Cossery called "a blunder, a minor incident".

The crime though brings in Nour El Dine, the police inspector. This was a man who longed for a criminal as clever as he thought himself to be. Convinced that one of Gohar, Yeghen, or El Kordi was the murderer, he tried to engage each in turn on a personal level. However, he soon discovered "these disreputable intellectuals were forever breaking down all sense of authority in him". They had no idea of his world of institutions and government.

It is this play off between his world and theirs, the questions it raises in his policeman's mind, that are the substance and delight of this book.

________________

Albert Cossery (1913-2008) was born in Cairo and educated in French language schools. In 1945 he settled permanently in Paris, winning the Grand Prix de la francophonie de l'Académie française in 1990. It is this blend of Egyptian and French backgrounds which makes his writing so individual.

12tonikat

This catch up is very enjoyable, I'm intrigued by both Spanish books and now Cossery. I may even try Mina someday, I don't know Glasgow really, but in some ways not wholly dissimilar to these parts, whilst very different in many.

13Caroline_McElwee

Enjoyed catching up with your reading Sassy. Looking forward to what 2018 brings.

14kidzdoc

Great reviews, Sassy! Thanks for reminding me about Mercè Rodoreda; I enjoyed her best known novel The Time of the Doves and I own at least two other books writtten by her that I haven't read yet.

16SassyLassy

>12 tonikat: >13 Caroline_McElwee: >14 kidzdoc: Thanks all. The three in translation were all new authors to me and it's always good when you discover new authors you like.

Doc, I just read your review of The Time of the Doves and I will have to follow up on it. It looks quite different in story line, but similar in theme.

>15 avaland: Come visit!

ETA sadly it is not my boat.

Doc, I just read your review of The Time of the Doves and I will have to follow up on it. It looks quite different in story line, but similar in theme.

>15 avaland: Come visit!

ETA sadly it is not my boat.

17SassyLassy

26. Hillbilly Elegy by J D Vance

first published 2016

finished reading August 4, 2017

J D Vance is a very angry man. This made Hillbilly Elegy the biggest disappointment of my reading year. It was a book I had been waiting for in paperback, and when I found it would not be released in Canada until 2018, I ordered it from the UK rather than wait.

Vance accurately identifies class in Greater Appalachia as the major problem of working class whites. Class divisions are not something Americans are keen to acknowledge, but he brings them out in the open. However, Vance is not angry with the institutions and people who hold this class back; he's angry with the very people in it.

Vance feels part of the problem is not lack of jobs for this group, but rather "... a lack of agency -- a feeling that you have little control over your life and a willingness to blame everyone but yourself." He claims "It's about reacting to bad circumstances in the worst way possible. It's ... a culture that increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it." Hard to counteract something when you feel you have little control. Vance has turned on the very people he purports to elegize.

The rough outlines of his life are well known by now: absent father, addicted mother, raised by grandparents, Iraqi war veteran, Yale Law School with financial aid. An elegy implies a sympathy or attachment to a vanishing entity or way of life, but Vance has turned into the kind of "If I can do it, why can't you?" ideologue that saps the energy out of those encountering hurdles along the way, possibly the same hurdles Vance himself encountered.

The ideological identification Vance gives himself is "modern conservative". Yet surely after all his travails on the path to Yale, and his full blown confrontation there with American elites, people whose existence he had never imagined, it might be more logical for him to take a more nuanced look at those left behind, and at the institutions and attitudes that work to keep them there.

18RidgewayGirl

Excellent review of Hillbilly Elegy.

19mabith

You might find this article about Hillbilly Elegy interesting. It certainly spoke to me and feelings I had about the general trend of the book's contents (so far as I could tell from reviews and quotes).

I Grew Up in Poverty in Appalachia, JD Vance's Hillbilly Elegy Doesn't Speak for Me

I Grew Up in Poverty in Appalachia, JD Vance's Hillbilly Elegy Doesn't Speak for Me

20kidzdoc

Great review of Hillbilly Elegy, Sassy. I bought it last year, but I won't read it.

21SassyLassy

>18 RidgewayGirl: Thanks

>19 mabith: Thanks for that article. It's a great op ed piece, well thought out.

>20 kidzdoc: My copy won't be shelved, but will be going out the door.

>19 mabith: Thanks for that article. It's a great op ed piece, well thought out.

>20 kidzdoc: My copy won't be shelved, but will be going out the door.

22SassyLassy

Janette Turner Hospital is an author I always search for in second hand bookstores, about the only bookstores where you can find her work.

27. Borderline by Janette Turner Hospital

first published 1985

finished reading August 14, 2017

So begins Janette Turner Hospital's novel Borderline. Those who have read her will recognize this a classic Hospital; new readers have a highly individual voice to discover.

The border here is at first a simple border between the US and Canada. All border crossings are fraught with unease for the traveller, with their potential for something truly out of the ordinary to happen. Gus sat in the hot sun waiting his turn at the checkpoint, feeling mildly guilty, contemplating the woman in the next lane in her sports car. Suddenly all hell broke looses as the customs agent opened the door of the meat van in front of him. Central American refugees poured out. Gus and Felicity, the American woman in the sports car, decided on the spot to scoop up one of these refugees, Dolores Marquez, whom they would later know as La Desconocida.

These were facts. The rest maybe factual or partly factual, or the work of the imagination. The borders are unclear. The story comes from the speculation and sleuthing of Jean Marc Seymour, writing a year later after the three have all disappeared. Facts about the trio have been presented to him by various government agencies and by police.

Janette Turner Hospital is an author who takes the real into the surreal, then into the imagination and back again, leaving her characters and the reader wondering which was which, having to confront the illusions of normal and ordinary. This is her third novel, one where politics starts to become integral. This is a writer for whom politics is as central as it is to the novels of Joan Didion. but with more of a lushness of prose, a feeling of tropical things creeping in, giving her work the menace of Vargas Llosa or Robert Stone. This is more apparent in her later novels, but can certainly be seen here.

This early work was a lucky find.

27. Borderline by Janette Turner Hospital

first published 1985

finished reading August 14, 2017

At borders, as at death and in dreams, no amount of prior planning will necessarily avail. The law of boundaries applies. In the nature of things, control is not in the hands of the traveller.

So begins Janette Turner Hospital's novel Borderline. Those who have read her will recognize this a classic Hospital; new readers have a highly individual voice to discover.

The border here is at first a simple border between the US and Canada. All border crossings are fraught with unease for the traveller, with their potential for something truly out of the ordinary to happen. Gus sat in the hot sun waiting his turn at the checkpoint, feeling mildly guilty, contemplating the woman in the next lane in her sports car. Suddenly all hell broke looses as the customs agent opened the door of the meat van in front of him. Central American refugees poured out. Gus and Felicity, the American woman in the sports car, decided on the spot to scoop up one of these refugees, Dolores Marquez, whom they would later know as La Desconocida.

These were facts. The rest maybe factual or partly factual, or the work of the imagination. The borders are unclear. The story comes from the speculation and sleuthing of Jean Marc Seymour, writing a year later after the three have all disappeared. Facts about the trio have been presented to him by various government agencies and by police.

"Look", they say, picking one up. They hold it up to the light, they turn it around, they push it in front of your eyes. Fact they say. As though it had magic properties. As though they have you squirming on a hook. Now how do you explain? they demand.Jean Marc, Felicity's long time friend, can reach entirely different conclusions and wonder if they are true. He can deny facts and substitute explanations. He knows borderlines can shift between narrators, between couples, from country to country, and most of all between truths.

Janette Turner Hospital is an author who takes the real into the surreal, then into the imagination and back again, leaving her characters and the reader wondering which was which, having to confront the illusions of normal and ordinary. This is her third novel, one where politics starts to become integral. This is a writer for whom politics is as central as it is to the novels of Joan Didion. but with more of a lushness of prose, a feeling of tropical things creeping in, giving her work the menace of Vargas Llosa or Robert Stone. This is more apparent in her later novels, but can certainly be seen here.

This early work was a lucky find.

23SassyLassy

I read someone else's review of this book on CR earlier this year and ordered it immediately. Apologies, as I now can't remember whose thread it was, but thank you as well. I'll reread and dip into this book in the future.

28. Sudden Death by Álvaro Enrigue translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer 2016

first published as Muerte súbita in 2013

finished reading August 19, 2017

Sudden Death is a wonderful book, but indescribable. Imagine a duel between the painter Caravaggio and the poet Quevedo, a duel fought as a tennis match. Nor is the duel the only thing that makes this match unusual, for the ball in play is made from the shorn hair of Ann Boleyn, taken as payment by her French executioner, for

On the other side of the world, Hernan Cortés was striding across the Americas, decimating the nations he found there. Vasco de Quiroga, the lawyer turned bishop, will try to make a European state of of the remnants, using ideas gleaned from Thomas More's Utopia, translated into Spanish by Quevedo himself. Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Inquisition rages, the CounterReformation looms. Enrigue moves back and forth with the speed and force of the tennis ball in the game that is still being fought.

However, toward the end of the book, Enriigue tell the reader "As I write, I don't know what this book is about." He says, "It isn't a book about Caravaggio or Quevedo, though Caravaggio and Quevedo are in the book, as are Cortés and Cuauhtémoc, and Galileo and Pius IV. Gigantic individuals facing off." Furthermore, "I know that as I wrote it I was angry because the bad guys always win."

History as a straight line, one thing leading to another, distorts what was. Enrigue shatters that linearity, returning this time to the wonderful, chaotic miasma it was, where things happened simultaneously, or out of turn, and no one knew the outcome.

Highly recommended.

28. Sudden Death by Álvaro Enrigue translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer 2016

first published as Muerte súbita in 2013

finished reading August 19, 2017

Sudden Death is a wonderful book, but indescribable. Imagine a duel between the painter Caravaggio and the poet Quevedo, a duel fought as a tennis match. Nor is the duel the only thing that makes this match unusual, for the ball in play is made from the shorn hair of Ann Boleyn, taken as payment by her French executioner, for

... the hair of those executed on the scaffold had special properties that caused it to trade at stratospheric prices among ball makers in Paris. A woman's hair was worth more, red hair still more, and a reigning queen's would command an unimaginable price.

On the other side of the world, Hernan Cortés was striding across the Americas, decimating the nations he found there. Vasco de Quiroga, the lawyer turned bishop, will try to make a European state of of the remnants, using ideas gleaned from Thomas More's Utopia, translated into Spanish by Quevedo himself. Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Inquisition rages, the CounterReformation looms. Enrigue moves back and forth with the speed and force of the tennis ball in the game that is still being fought.

However, toward the end of the book, Enriigue tell the reader "As I write, I don't know what this book is about." He says, "It isn't a book about Caravaggio or Quevedo, though Caravaggio and Quevedo are in the book, as are Cortés and Cuauhtémoc, and Galileo and Pius IV. Gigantic individuals facing off." Furthermore, "I know that as I wrote it I was angry because the bad guys always win."

History as a straight line, one thing leading to another, distorts what was. Enrigue shatters that linearity, returning this time to the wonderful, chaotic miasma it was, where things happened simultaneously, or out of turn, and no one knew the outcome.

Highly recommended.

24SassyLassy

This book had been on the TBR pile for a long time, but Reading Globally's third quarter, Minority Language Writers in their own Country, brought it out

29. Solitude by Caterina Albert i Paradís published under the pseudonym Victor Català, translated from the Catalan by David Rosenthal, 1992

- first published in serial form in the magazine Joventut in 1904-5, published in book form in 1905 as Solitud

finished reading August 24, 2017

Solitude is one of those tales, seemingly so simple, that carry you along right from the beginning, almost as if you are listening to a skilled storyteller.

Recently wed Mila and Matias were travelling to their new home and his new job. Matias had been quite vague about both, but Mila was excited enough about her new life to accept at face value what little information he had given her. Initially they had travelled by cart, but now the Catalan mountains had become so steep that they would have to complete their journey on foot. Mila grew more and more apprehensive.

Finally they reached their destination, a hermitage and chapel dedicated to St Pontius, ironically the "patron of good health". They were to be the new custodians. The shepherd Gaietà and the boy Baldiret were there to greet them.

Mila and Matias now became "Hermit" and Hermitess"; Gaietà was "Shepherd". Mila hated this form of address, this loss of identity, the inability to see beyond the role. "Hermitess" served as a constant reminder to her of her isolation, especially as Matias spent more and more time away.

Solitude need not equate to loneliness. The shepherd worked hard to tell Mila the stories of the mountain, its rocks, trees, streams and spirits. He knew what loneliness and melancholy could do to her if she let them intrude. He wanted her to see her new world in the way he understood it; to become one with it. He wanted her free from the evil forces on the mountain, both natural and human.

Mila's struggle to adapt could be seen as any young woman's journey to adulthood. However, Paradís creates such a tension between the mountain's opposing forces that Mila becomes the embodiment of the struggle to attain psychological and sexual self awareness. There is very little explicit here. Solitude was first published in serial form in 1904-5, well before such themes built around female characters gained acceptance. Paradís had to publish under a male pseudonym, Victor Català, although her identity was known to her publisher.

Apart from her pseudonym, there is nothing overtly Catalan about this novel. The story would be as credible in settings like Greece or Albania. Later, however, it was affected by the Spanish Civil War. In the author's 1945 foreword to this, the fifth edition of Solitude, she says two additional chapters, left out of the earlier editions, were intended to be reintegrated in a new 1937 edition. "However, the fratricidal war, which wrecked so many things with its obstacles and unforeseen upheavals, paralyzed publication temporarily, and when I returned home, it was to a disagreeable surprise." A search of her home under a flimsy pretext "... had turned the whole house upside-down", and the two chapters had disappeared.

This 1992 translation by David Rosenthal is the first translation into English of a book the publishers say is "... the most important Catalan novel to appear before the Spanish Civil War."

29. Solitude by Caterina Albert i Paradís published under the pseudonym Victor Català, translated from the Catalan by David Rosenthal, 1992

- first published in serial form in the magazine Joventut in 1904-5, published in book form in 1905 as Solitud

finished reading August 24, 2017

Solitude is one of those tales, seemingly so simple, that carry you along right from the beginning, almost as if you are listening to a skilled storyteller.

Recently wed Mila and Matias were travelling to their new home and his new job. Matias had been quite vague about both, but Mila was excited enough about her new life to accept at face value what little information he had given her. Initially they had travelled by cart, but now the Catalan mountains had become so steep that they would have to complete their journey on foot. Mila grew more and more apprehensive.

Suddenly Mila halted and turned around, astounded: Holy Virgin! How far they'd travelled that day!

Beneath them she saw nothing but waves of mountain, huge, silent mountains that sloped into the quiet dusk, which enveloped them in shadow like a darkening cloud.

Mila searched that blue emptiness for a wisp of smoke, a hut, a human figure... But she saw nothing, not the slightest indication that they shared the landscape with other human beings.

"How lonely!" she mumbled, stunned and feeling her spirit grow as dark or darker than those shady depths.

Finally they reached their destination, a hermitage and chapel dedicated to St Pontius, ironically the "patron of good health". They were to be the new custodians. The shepherd Gaietà and the boy Baldiret were there to greet them.

Mila and Matias now became "Hermit" and Hermitess"; Gaietà was "Shepherd". Mila hated this form of address, this loss of identity, the inability to see beyond the role. "Hermitess" served as a constant reminder to her of her isolation, especially as Matias spent more and more time away.

Solitude need not equate to loneliness. The shepherd worked hard to tell Mila the stories of the mountain, its rocks, trees, streams and spirits. He knew what loneliness and melancholy could do to her if she let them intrude. He wanted her to see her new world in the way he understood it; to become one with it. He wanted her free from the evil forces on the mountain, both natural and human.

Mila's struggle to adapt could be seen as any young woman's journey to adulthood. However, Paradís creates such a tension between the mountain's opposing forces that Mila becomes the embodiment of the struggle to attain psychological and sexual self awareness. There is very little explicit here. Solitude was first published in serial form in 1904-5, well before such themes built around female characters gained acceptance. Paradís had to publish under a male pseudonym, Victor Català, although her identity was known to her publisher.

Apart from her pseudonym, there is nothing overtly Catalan about this novel. The story would be as credible in settings like Greece or Albania. Later, however, it was affected by the Spanish Civil War. In the author's 1945 foreword to this, the fifth edition of Solitude, she says two additional chapters, left out of the earlier editions, were intended to be reintegrated in a new 1937 edition. "However, the fratricidal war, which wrecked so many things with its obstacles and unforeseen upheavals, paralyzed publication temporarily, and when I returned home, it was to a disagreeable surprise." A search of her home under a flimsy pretext "... had turned the whole house upside-down", and the two chapters had disappeared.

This 1992 translation by David Rosenthal is the first translation into English of a book the publishers say is "... the most important Catalan novel to appear before the Spanish Civil War."

25SassyLassy

It was Labour Day weekend, the weather was glorious, summer was waning, and unpacking indoors was out of the question. A quick break on the porch was needed.

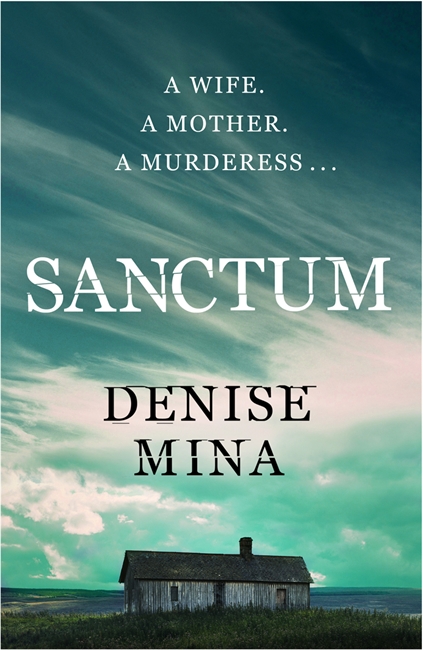

30. Sanctum by Denise Mina

first published 2002

finished reading September 2, 2017

Susie Harriot, a forensic psychiatrist, was convicted of the murder of Andrew Gow, free on appeal for conviction on serial murder charges. Harriot had been Gow's prison psychiatrist. Somewhat improbable, I know, but I didn't write it.

Harriot was remanded for psychiatric examination before sentencing, at which time there will be no appeal.

Harriot's husband, a doctor turned house husband, retreated each night to Susie's study, the sanctum. There, using his wife's computer, he tried desperately to prove her innocence by going through her files. He learned much about her, confirming the dictum that you shouldn't snoop. That aside, he used his findings, laboriously recording them nightly, along with his thoughts, to map out his theory about the case.

Sanctum is the first standalone novel Mina wrote after her breakout Garnethill trilogy. It served its purpose as an entertaining quick break, but that was it.

30. Sanctum by Denise Mina

first published 2002

finished reading September 2, 2017

Susie Harriot, a forensic psychiatrist, was convicted of the murder of Andrew Gow, free on appeal for conviction on serial murder charges. Harriot had been Gow's prison psychiatrist. Somewhat improbable, I know, but I didn't write it.

Harriot was remanded for psychiatric examination before sentencing, at which time there will be no appeal.

Harriot's husband, a doctor turned house husband, retreated each night to Susie's study, the sanctum. There, using his wife's computer, he tried desperately to prove her innocence by going through her files. He learned much about her, confirming the dictum that you shouldn't snoop. That aside, he used his findings, laboriously recording them nightly, along with his thoughts, to map out his theory about the case.

Sanctum is the first standalone novel Mina wrote after her breakout Garnethill trilogy. It served its purpose as an entertaining quick break, but that was it.

26SassyLassy

Agnes Grey was next in the Virago Group's Chronological Read programme.

31.Agnes Grey by Anne Bronte

first published 1846 in the same volume as Wuthering Heights

finished reading Sept 9 2017

Agnes Grey is the story of a young and sheltered woman who goes out into the world as a governess in order to help her family in its straitened circumstances. Basically, this part is Anne Bronte's story, as this is what she too had to do. Raised in a remote parsonage, Anne had very little experience of the world. This is evident in the surprise and hurt Agnes displays in reaction to the ill treatment she received in the homes of her employers.

I first read this book at twelve or thirteen, and with minimal world experience myself at that time, thought Agnes's reactions were quite appropriate. Similarly, I had nothing to measure against the courtship by Mr Weston. Reading the novel today, it all seems stiff and wooden. Anne's lack of experience with suitors is evident. This lack is not a bad thing, but it makes the couple's dialogues read like a parody of Victorian literature. So, interesting in a developmental way, but it you want to see the writer Anne would become, read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

31.Agnes Grey by Anne Bronte

first published 1846 in the same volume as Wuthering Heights

finished reading Sept 9 2017

Agnes Grey is the story of a young and sheltered woman who goes out into the world as a governess in order to help her family in its straitened circumstances. Basically, this part is Anne Bronte's story, as this is what she too had to do. Raised in a remote parsonage, Anne had very little experience of the world. This is evident in the surprise and hurt Agnes displays in reaction to the ill treatment she received in the homes of her employers.

I first read this book at twelve or thirteen, and with minimal world experience myself at that time, thought Agnes's reactions were quite appropriate. Similarly, I had nothing to measure against the courtship by Mr Weston. Reading the novel today, it all seems stiff and wooden. Anne's lack of experience with suitors is evident. This lack is not a bad thing, but it makes the couple's dialogues read like a parody of Victorian literature. So, interesting in a developmental way, but it you want to see the writer Anne would become, read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

27Caroline_McElwee

>23 SassyLassy: ouch hit by a bullet at year’s end Sassy. I’m a big Caravaggio fan.

28SassyLassy

>27 Caroline_McElwee: Enrigue says in his Bibliographic Note that there are two recent Caravaggio biographies he couldn't have done without when writing this book: Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane and M: The Man who became Caravaggio. I see you have both of them in your library. He also credits Graham-Dixon with establishing the link between Caravaggio's paintings of beheadings and his own death sentence. Given all that, I think you would enjoy the novel indeed.

29SassyLassy

This is another instance of reading a review on CR and deciding to order the book. I believe the review was by steventx or edwin. In this case it has taken awhile to get to reading it.

This was perhaps my favourite book of the year.

32. The Land Breakers by John Ehle

first published 1964

finished reading Sept 16, 2017

Back in 1779, the land that would become the United States was one of opportunity and possibility. Mooney and Imy Wright, immigrants from Ulster and former indentured servants, had walked and worked their way for three years from Philadelphia to Morgantown in the crown colony of North Carolina. There they bought a huge tract of land from the storekeeper. Their new land was almost a week's walk up into the mountains, so far that the river there flowed to the west. Mooney and Imy cleared some land and built a cabin. They were completely alone in this new world, the world of the mountain and its creatures.

Nobody gets to stay alone in a rich new land like that though. By January of the new year, Tinkler Harrison and his family, slaves and entourage had moved to the area too. Others followed.

Ehle tells the story of total strangers, washed up together in the same spot, trying to form a community. Beautiful and bountiful though it may be, this is not the Garden of Eden. More than serpents live here; there are also bears and panthers, floods and droughts. Among the settlers there were divisions, some of which would never be overcome.

Ehle had worked as a radio dramatist and his ear for dialogue comes through. Despite the violence of the land, the language is beautiful, with a sense of peace to it, a pastoral lyric which makes the unthinkable that much worse when it intrudes. This is a book to which I can't do justice.

The Land Breakers is the first book in a seven volume series, the Mountain Novels, which follow the land breakers up to the 1930s, however it can certainly be read on its own.

This was perhaps my favourite book of the year.

32. The Land Breakers by John Ehle

first published 1964

finished reading Sept 16, 2017

Back in 1779, the land that would become the United States was one of opportunity and possibility. Mooney and Imy Wright, immigrants from Ulster and former indentured servants, had walked and worked their way for three years from Philadelphia to Morgantown in the crown colony of North Carolina. There they bought a huge tract of land from the storekeeper. Their new land was almost a week's walk up into the mountains, so far that the river there flowed to the west. Mooney and Imy cleared some land and built a cabin. They were completely alone in this new world, the world of the mountain and its creatures.

Nobody gets to stay alone in a rich new land like that though. By January of the new year, Tinkler Harrison and his family, slaves and entourage had moved to the area too. Others followed.

Ehle tells the story of total strangers, washed up together in the same spot, trying to form a community. Beautiful and bountiful though it may be, this is not the Garden of Eden. More than serpents live here; there are also bears and panthers, floods and droughts. Among the settlers there were divisions, some of which would never be overcome.

Ehle had worked as a radio dramatist and his ear for dialogue comes through. Despite the violence of the land, the language is beautiful, with a sense of peace to it, a pastoral lyric which makes the unthinkable that much worse when it intrudes. This is a book to which I can't do justice.

The Land Breakers is the first book in a seven volume series, the Mountain Novels, which follow the land breakers up to the 1930s, however it can certainly be read on its own.

30SassyLassy

Not caught up on the year yet, but off to do New Year's Eve things.

Happy New Year to all! May things be better next year.

Happy New Year to all! May things be better next year.

31Caroline_McElwee

>29 SassyLassy: ouch, another hit.

>28 SassyLassy: I really like Andrew Graham-Dixon’s work. He’s made a couple of good documentaries about Caravaggio over the years.

>28 SassyLassy: I really like Andrew Graham-Dixon’s work. He’s made a couple of good documentaries about Caravaggio over the years.

32SassyLassy

33. Blue Remembered Hills by Rosemary Sutcliff

first published 1983

finished reading Sept 24, 2017

There was a time when every school and children's library held novels by Rosemary Sutcliff. They can still be found in more out of the way places, books like Eagle of the Ninth and Sword at Sunset. Blue Remembered Hills is the author's memoir of her childhood, written in her early sixties.

Her father was an English naval officer and the family travelled to Malta with him in the 1920s and back to England. However, Rosemary developed juvenile arthritis, Still's disease, a condition that would alter her life and that of her family completely. She and her mother lived in a series of rented accommodations while her father was away at sea. The treatments she underwent during this time were horrendous, but it was an age when there were no drugs to alleviate the condition.

Sutcliff writes of this very matter of factly. The descriptions of the children's hospital in Exeter where she underwent a series of surgeries are perhaps the most interesting, opening a window to the child's point of view. She hints at the difficulties of living alone with her mother, who Rosemary felt was bipolar. By the time she was fourteen, Sutcliff had convinced her family to allow her to go to art school, where she became a skilled miniaturist.

Had Sutcliff restricted herself to her life with her family, her schools, travels and health, it would have been interesting enough reading, for she is a skilled writer and able to leaven her story with humour. However, back in the outside world, Sutcliff can be tiresome indeed. She prattles on about her relatives and their foibles, people she meets along the way, anything at all. Underlying it all is a definite whiff of English middle class smugness, but I suspect some will find her charming.

The one area where her strength came through was in her discussion of living with the disease and what it meant for any potential relationship. Here she was way ahead of her time in calling for a recognition that "... we have the same emotional needs as anybody else...", something that the society of the 1930s would have found difficult to accommodate.

The blue remembered hills are those of Devon, where the family moved once her father retired. Sutcliff does write of the natural world, which she loved, with a real affinity. All in all though, I think if someone wanted to read her, it might be best to try one of the more than forty novels she wrote. This is the second author's memoir from Slightly Foxed I've read this year. I'm beginning to have a different view of those who write for children.

33thorold

>23 SassyLassy: Taking note of Sudden death - that sounds like fun! I still remember being bowled over by Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio film.

>32 SassyLassy: Haven’t read anything by Sutcliff since I was about 12, but she’s one of the few children’s authors I could easily imagine going back to some time.

>32 SassyLassy: Haven’t read anything by Sutcliff since I was about 12, but she’s one of the few children’s authors I could easily imagine going back to some time.

35SassyLassy

34. The Birdwatcher by William Shaw

first published 2016

finished reading October 1, 2017

Despite my recent dips into the field, I don't read much crime fiction, so William Shaw was an author new to me, although the book's cover seemed to indicate I should know him.

Naturally there is a murder. The victim is Bob Rayner, Sergeant South's neighbour and close friend. Both South and his neighbour lived alone on a stretch of beach on the English Channel, a stretch where only people who wished to be alone lived. They shared a mutual bond as bird watchers.

Nothing much there to predict a murder. As the narrative unfolds, their separate lives are slowly revealed, with surprises in each. As an investigating officer, South finds much about Rayner he knew nothing about, leading him to question how well we really know those we call friends. South is an apt person to question this, as there are things in his past as well that he has never revealed, and the reader slowly discovers these.

Shaw writes this kind of fiction well, letting the reader think it through. The end leaves a quandry for the reader over a sympathetic character. This was a good book in its genre.

36SassyLassy

35. The Day of the Owl by Leonardo Sciascia translated from the Italian by Archibald Colquhoun and Arthur Oliver

first published as Il Giorno della civetta in 1961

finished reading October 9, 2017

Right now I can't find my copy of this book. That's a pity, as it means I can't quote from it to give an indication of just how good it is. It's everything a crime story should be. A man is murdered in broad daylight at a bus stop in Sicily. Naturally, no one saw anything. Captain Bellodi, the detective who must solve the murder, was a northern Italian, slowly learning the ways of Sicily. This was to be a total immersion for him.

Sciasicia is a superb writer, credited with creating a genre of "metaphysical" mysteries. He is not afraid to take risks, for even to mention the Mafia at the time this book was published was dangerous. Sciasicia was also a political writer, who would take more risks later in his career with The Moro Affair, which continued his investigation into the links between crime and government, in that case in the real world. This is a writer well worth reading.

37SassyLassy

Still deluding myself that I will finish 2017

36. Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes by Mollie Panter-Downes

first published 1999, individual stories and articles published in The New Yorker during WWII

finished reading October 17, 2017

Needing a short story one afternoon, I picked up Mollie Panter-Downes's Good Evening, Mrs Craven. It was a pleasant surprise. I had feared it might be too home county, too stiff upper lip. Instead, there was humour and a very keen eye. It does reflect the lives of rural upper middle class women during WWII, but it is able to gently mock them as they are forced to adapt to new realities.

The stories here tell of volunteer committee meetings, love affairs, billeting evacuees from the cities, guilt over desk jobs -- a whole gamut of situations. They were published in The New Yorker magazine during the war. In part, they reflect a view of the war at home in England that the American readers would expect, but there is more of a ring of truth to them than that.

Mollie Panter-Downes wrote 852 pieces for the magazine in the almost fifty years from 1938-1987. These included her column "Letter from London", designed like "Letter from Paris", to let affluent New Yorkers know what was going on in places they frequented. Panter-Downes thought of herself as a reporter, but these stories add a human element to reportage. There is a follow-up volume, Minnie's Room: The Peacetime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes. Both are published by Persephone. It would be interesting to see if peace removes the enjoyable edge. Somehow I suspect not.

________________

For those who love the endpapers of Persephone Books, each of which features a fabric that relates to the particular book, this one is 'Coupons', from 1941. The background is a series of the number 66, which was the number of clothes coupons allowed each year during the war and showing how many were needed for each item of clothing displayed.

36. Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes by Mollie Panter-Downes

first published 1999, individual stories and articles published in The New Yorker during WWII

finished reading October 17, 2017

Needing a short story one afternoon, I picked up Mollie Panter-Downes's Good Evening, Mrs Craven. It was a pleasant surprise. I had feared it might be too home county, too stiff upper lip. Instead, there was humour and a very keen eye. It does reflect the lives of rural upper middle class women during WWII, but it is able to gently mock them as they are forced to adapt to new realities.

The stories here tell of volunteer committee meetings, love affairs, billeting evacuees from the cities, guilt over desk jobs -- a whole gamut of situations. They were published in The New Yorker magazine during the war. In part, they reflect a view of the war at home in England that the American readers would expect, but there is more of a ring of truth to them than that.

Mollie Panter-Downes wrote 852 pieces for the magazine in the almost fifty years from 1938-1987. These included her column "Letter from London", designed like "Letter from Paris", to let affluent New Yorkers know what was going on in places they frequented. Panter-Downes thought of herself as a reporter, but these stories add a human element to reportage. There is a follow-up volume, Minnie's Room: The Peacetime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes. Both are published by Persephone. It would be interesting to see if peace removes the enjoyable edge. Somehow I suspect not.

________________

For those who love the endpapers of Persephone Books, each of which features a fabric that relates to the particular book, this one is 'Coupons', from 1941. The background is a series of the number 66, which was the number of clothes coupons allowed each year during the war and showing how many were needed for each item of clothing displayed.

38AnnieMod

>36 SassyLassy: >37 SassyLassy:

Had you raided my bookcase (singular - these two live in the same bookcase in my house)? :) Awesome reviews - that may move both of these closer to the top of the pile on my table (the nightstand does not have enough space for all the books I am pulling out :) )

Had you raided my bookcase (singular - these two live in the same bookcase in my house)? :) Awesome reviews - that may move both of these closer to the top of the pile on my table (the nightstand does not have enough space for all the books I am pulling out :) )

39SassyLassy

>38 AnnieMod: That's too funny and the combination is so unlikely! Try the Sciascia. It won't be on the table long, although I suspect it may be replaced by a couple more of his books.

40AnnieMod

>39 SassyLassy:

Well... NYRB and Persephone live together because they do not fit my genre collections and because they look so nice on a shelf when left on their own so I do not want to shelve them where they would fit genre wise. It was just funny that I have both (I probably have 25 of each of the collections and working on expanding both).

And I think I read The Owl a few years ago when I was slacking in adding books. I guess time to reread anyway - I remember liking it.

Well... NYRB and Persephone live together because they do not fit my genre collections and because they look so nice on a shelf when left on their own so I do not want to shelve them where they would fit genre wise. It was just funny that I have both (I probably have 25 of each of the collections and working on expanding both).

And I think I read The Owl a few years ago when I was slacking in adding books. I guess time to reread anyway - I remember liking it.

41SassyLassy

Life seemed to be getting back to normal by early October, after a crazy year. It was time to start reading Zola again, last visited in April. My reading of the full Rougon Macquart series was hampered by only reading those in English translation, and of those, only recent translations. I did not want bowdlerized versions. When I started the series in January 2016, these restrictions meant that of the twenty novels, I would be skipping 2, 9, 10 and 20 in the suggested reading order. I thought I was now at 18, but a quick check revealed two more translations had been released in 2017, so I happily went back to 9, The Sin of Abbé Mouret.

37. The Sin of Abbé Mouret translated from the French by Valerie Minogue 2017

first published as La Faute de Abbé Mouret in 1875

finished reading October 25, 2017

The Sin of Abbé Mouret starts out in almost wooden fashion, reminiscent of The Crime of Father Amaro, published the same year. Serge Mouret was a young priest, fresh out of the seminary. Prayer and devotion meant so much to him that he found it almost impossible to imagine the struggles other priests might have with their less spiritual sides. However, this is Zola, and the themes and descriptions soon let the reader know it.

Serge was a product of both the Rougons and Macquarts. His mother was from the respectable Rougon side of the family, and his father from the tainted Macquart side. Since Zola's aim was to study family, heredity and environment, we know that such a lineage will be fraught with tension and turmoil. Furthermore, not only was Serge's father committed to an asylum, perhaps expected as a Macquart, Serge's mother could be seen as suffering from mental instability at the end of The Conquest of Plassans, when she fell under the influence of the terrifying Abbé Faujas.

Serge had not only renounced the world of the flesh when he took his priestly vows, he also renounced the material world. He was now living in Les Artaud with a housekeeper and his mentally deficient younger sister Désirée. He had given his money to his much more worldly older brother Octave, from Pot Luck and The Ladies' Paradise. Les Artaud was not the place to be though for a man who found such disturbance in what he considered to be carnal sins. The villagers were all related, were wildly promiscuous, and barely paid lip service to the rites of the Catholic Church, a religion Zola shows as completely unable to meet their needs. Nature also showed no respect. Chickens pecked on the stone floor of the church, birds flew through the broken windows, a rowan tree thrust its branches in. At the altar, the priest, lost in his devotions, ... did not even hear this invasion of the nave by the warm May morning, or the rising flood of sunshine, greenery, and birds, which overflowed even up to the foot of Calvary, on which nature, dammed, lay dying. Nature was already fighting him.

Just outside the village, was a magic estate, Paradou. It had been abandoned a century before. Built in the time of Louis XV, it was like a little Versailles. But the lady of the Paradou must have died there, for she was never seen again after the first season. The following year, the chateau burned down, the park gates were nailed up, and even the narrow slits in the wall filled up with earth, so ever since that distant era, no eye had penetrated the vast enclosure which occupied the whole of one of the high plateaux of the Garrigues. Nature there was left to run riot.

The place was looked after by the caretaker Jeanbernat, the Philosopher, who took care to lodge outside the walls. His sixteen year old niece lived with him. Serge first went to Paradou with his uncle Dr Pascal, the family recorder, to visit Jeanbernat who was rumoured to be dying. Jeanbernat represents the rationalists and the voice of reason against dogma, and as such felt no reticence in challenging Serge on his beliefs. It was here that the Abbé caught his first glimpse of Albine, This blonde child, with her long face, aflame with life, seemed to him to be the mysterious and disturbing daughter of that forest he had glimpsed in a patch of light when he first arrived.

Since the age of five, Serge had been devoted to the Virgin Mary, so white, so pure. He thought of her as a divine sister, the two of them innocents in a sinful world. His priestly devotions had continued that marian focus. Mary was the only representation of the divine to grace his cell; Mary, the ever pure, in an image of the Immaculate Conception. Now, suddenly, he could not help seeing her with the eyes of an adolescent. He feared to contaminate her with his impure thoughts as her image became confused with that of Albine. Feverish, rambling, he prayed.

Here the book shifts. Serge awoke in a strange room, festooned with fading images of cherubs. Albine was his nurse. He had been there some time. As he convalesced, Albine coaxed him outdoors into the gardens of the Paradou. Gradually the two innocents explored her paradise together in Zola's version of the Garden of Eden. The horticulturalist might quibble that the combinations of blooms Zola gathers don't occur in the real world, but this is the Garden, where all things are possible. There are pages and pages of incredibly lush descriptions of the animals, trees and flowers, done with incredible and accurate detail, everything with voluptuous overtones:

However, just as in the original Garden, there is a forbidden tree and there is a fall. Serge, whose illness had resulted in his forgetting his priestly life, suddenly recalled it, and was driven from the garden. The clash of religion and reality resumed, for Serge and internal one, for Zola an eternal one.

___________________

One thing I did wonder about was the translation of the title, in French La Faute de Abbé Mouret which to me is more a fault or an error, both of which fit here, than an actual sin. Of course, as the English title indicates, Mouret does commit a sin in the eyes of the Church, but I would think of that as le péché, not une faute. Could some francophone please help me out here?

37. The Sin of Abbé Mouret translated from the French by Valerie Minogue 2017

first published as La Faute de Abbé Mouret in 1875

finished reading October 25, 2017

The Sin of Abbé Mouret starts out in almost wooden fashion, reminiscent of The Crime of Father Amaro, published the same year. Serge Mouret was a young priest, fresh out of the seminary. Prayer and devotion meant so much to him that he found it almost impossible to imagine the struggles other priests might have with their less spiritual sides. However, this is Zola, and the themes and descriptions soon let the reader know it.

Serge was a product of both the Rougons and Macquarts. His mother was from the respectable Rougon side of the family, and his father from the tainted Macquart side. Since Zola's aim was to study family, heredity and environment, we know that such a lineage will be fraught with tension and turmoil. Furthermore, not only was Serge's father committed to an asylum, perhaps expected as a Macquart, Serge's mother could be seen as suffering from mental instability at the end of The Conquest of Plassans, when she fell under the influence of the terrifying Abbé Faujas.

Serge had not only renounced the world of the flesh when he took his priestly vows, he also renounced the material world. He was now living in Les Artaud with a housekeeper and his mentally deficient younger sister Désirée. He had given his money to his much more worldly older brother Octave, from Pot Luck and The Ladies' Paradise. Les Artaud was not the place to be though for a man who found such disturbance in what he considered to be carnal sins. The villagers were all related, were wildly promiscuous, and barely paid lip service to the rites of the Catholic Church, a religion Zola shows as completely unable to meet their needs. Nature also showed no respect. Chickens pecked on the stone floor of the church, birds flew through the broken windows, a rowan tree thrust its branches in. At the altar, the priest, lost in his devotions, ... did not even hear this invasion of the nave by the warm May morning, or the rising flood of sunshine, greenery, and birds, which overflowed even up to the foot of Calvary, on which nature, dammed, lay dying. Nature was already fighting him.

Just outside the village, was a magic estate, Paradou. It had been abandoned a century before. Built in the time of Louis XV, it was like a little Versailles. But the lady of the Paradou must have died there, for she was never seen again after the first season. The following year, the chateau burned down, the park gates were nailed up, and even the narrow slits in the wall filled up with earth, so ever since that distant era, no eye had penetrated the vast enclosure which occupied the whole of one of the high plateaux of the Garrigues. Nature there was left to run riot.

The place was looked after by the caretaker Jeanbernat, the Philosopher, who took care to lodge outside the walls. His sixteen year old niece lived with him. Serge first went to Paradou with his uncle Dr Pascal, the family recorder, to visit Jeanbernat who was rumoured to be dying. Jeanbernat represents the rationalists and the voice of reason against dogma, and as such felt no reticence in challenging Serge on his beliefs. It was here that the Abbé caught his first glimpse of Albine, This blonde child, with her long face, aflame with life, seemed to him to be the mysterious and disturbing daughter of that forest he had glimpsed in a patch of light when he first arrived.

Since the age of five, Serge had been devoted to the Virgin Mary, so white, so pure. He thought of her as a divine sister, the two of them innocents in a sinful world. His priestly devotions had continued that marian focus. Mary was the only representation of the divine to grace his cell; Mary, the ever pure, in an image of the Immaculate Conception. Now, suddenly, he could not help seeing her with the eyes of an adolescent. He feared to contaminate her with his impure thoughts as her image became confused with that of Albine. Feverish, rambling, he prayed.

O Mary, Chosen Vessel, castrate in me all humanity, make me a eunuch among men, so you may without fear grant me the treasure of your virginity!

And Abbé Mouret, his teeth chattering, collapsed on the tiled floor, struck down by fever.

Here the book shifts. Serge awoke in a strange room, festooned with fading images of cherubs. Albine was his nurse. He had been there some time. As he convalesced, Albine coaxed him outdoors into the gardens of the Paradou. Gradually the two innocents explored her paradise together in Zola's version of the Garden of Eden. The horticulturalist might quibble that the combinations of blooms Zola gathers don't occur in the real world, but this is the Garden, where all things are possible. There are pages and pages of incredibly lush descriptions of the animals, trees and flowers, done with incredible and accurate detail, everything with voluptuous overtones:

The living flowers opened out like naked flesh, like bodices revealing the treasures of the bosom. There were yellow roses like petals from the golden skin of barbarian maidens, roses the colour of straw, lemon-coloured roses, and some the colour of the sun, all the varying shades of skin bronzed by ardent skies. Then the bodies grew softer, the tea roses becoming delightfully moist and cool, revealing what modesty had hidden, parts of the body not normally shown, fine as silk and threaded with a blue network of veins.

However, just as in the original Garden, there is a forbidden tree and there is a fall. Serge, whose illness had resulted in his forgetting his priestly life, suddenly recalled it, and was driven from the garden. The clash of religion and reality resumed, for Serge and internal one, for Zola an eternal one.

___________________

One thing I did wonder about was the translation of the title, in French La Faute de Abbé Mouret which to me is more a fault or an error, both of which fit here, than an actual sin. Of course, as the English title indicates, Mouret does commit a sin in the eyes of the Church, but I would think of that as le péché, not une faute. Could some francophone please help me out here?