The readings of JDHomrighausen, aka "the reader formerly known as lilbrattyteen," part 2.

Ce sujet est poursuivi sur The readings of JDHomrighausen, aka "the reader formerly known as lilbrattyteen," part 2..

DiscussionsClub Read 2013

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

Ce sujet est actuellement indiqué comme "en sommeil"—le dernier message date de plus de 90 jours. Vous pouvez le réveiller en postant une réponse.

1JDHomrighausen

Because the last thread was created by lilbrattyteen, not JDHomrighausen (I changed my username), I couldn't continue it.... so here I am.

I am changing my reading habits substantially. For one, I have fallen into the habit of reading light books so I can give them away. This is great for my TBR dent and my books-read quotient, but then I end up reading nothing but fluff. So I am scratching that idea.

I also have fallen into the habit of reading books and waiting a while to review them. This leads to bland reviews because the book is not fresh in my mind. Ho hum.

The list:

January 2013:

1. The Roman Empire and the New Testament: An Essential Guide (Essential Guides) by Warren Carter

2. The World is Charged: The Transcendent with Us by Francis R. Smith

3. The Critical Meaning of the Bible by Raymond E. Brown

4. The Anome by Jack Vance

5. The Christians as the Romans Saw Them by Robert Louis Wilken

6. An Introduction to Theology in Global Perspective by Stephen B. Bevans

7. The Sandman, Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes by Neil Gaiman

February 2013:

8. The Giver by Lois Lowry

9. The Book of Daniel (Cambridge Bible Commentaries on the Old Testament) by Raymond Hammer

10. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West by Donald S. Lopez Jr.

11. The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius

12. Megillat Esther by JT Waldman

13. Space Opera by Jack Vance

March 2013:

14. The British Discovery of Buddhism by Philip C. Almond

15. Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism by Miranda Shaw

16. King David by Kyle Baker

17. The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

18. Saints and Society: The Two Worlds of Western Christendom, 1000-1700 by Donald Weinstein

19. Autobiography of Charles Darwin

April 2013

20. My Life with the Saints by James Martin, S.J.

21. On Justice, Power, and Human Nature: The Essence of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

22. The Clouds by Aristophanes

23. Being Upright: Zen Meditation and the Bodhisattva Precepts by Reb Anderson

24. The Unconscious Christian: Images of God in Dreams (Jung and Spirituality) by James A. Hall

25. The Innocence of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton

26. The Diaries of Adam and Eve by Mark Twain

27. The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

28. The Life of Blessed Francis by Thomas of Celano

29. The Life of St. Francis of Assisi by St. Bonaventure

30. Lives of Roman Christian Women (Penguin Classics) by Carolinne White

31. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott

32. Minding God: Theology and the Cognitive Sciences by Gregory R. Peterson

33. Naturalism, Theism and the Cognitive Study of Religion: Religion Explained? by Aku Visala

34. The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin (read parts)

May 2013:

35. How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment by Eihei Dogen

36. Lilith, A Romance by George MacDonald

37. On Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and the Church in the Twenty-First Century by Jorge Mario Bergoglio and Abraham Skorka

38. Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine by Bart D. Ehrman

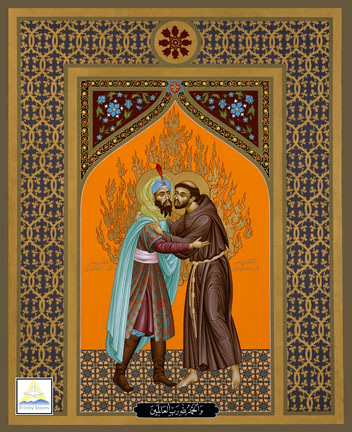

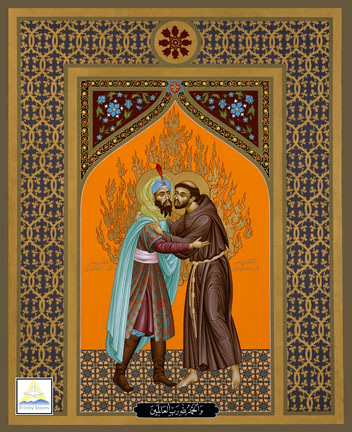

39. Daring to Cross the Threshold: Francis of Assisi Encounters Sultan Malek al-Kamil by Kathleen A. Warren

40. Saint Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter by John V. Tolan (partially read)

41. Collected Public Domain Works of H. P. Lovecraft by H. P. Lovecraft

42. Love's Executioner & Other Tales of Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom

43. The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins

44. The Selfish Genius: How Richard Dawkins Rewrote Darwin's Legacy by Fern Elsdon-Baker (partially read)

45. Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris

46. Welcome to the Episcopal Church: An Introduction to Its History, Faith, and Worship by Christopher L. Webber

47. How Biblical Languages Work: A Student's Guide to Learning Hebrew and Greek by Peter James Silzer

48. Dead Man Walking by Helen Prejean

49. The Dawkins Delusion?: Atheist Fundamentalism and the Denial of the Divine by Alister McGrath

50. Turning Suffering Inside Out by Darlene Cohen

51. The Nine Billion Names of God by Arthur C. Clarke

June 2013

52. When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet by Hildegard Diemberger

53. The Evolving God: Charles Darwin on the Naturalness of Religion by J. David Pleins

54. Charles Darwin: A Memorial Poem by George John Romanes

55. Islam & Franciscanism: A Dialogue (Spirit and Life Series Volume 9)

56. Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice by Thich Nhat Hanh

57. Introduction to Greek, 2/e by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine

58. Understanding Language: A Guide for Beginning Students of Greek & Latin by Donald Fairbairn

59. Surviving Paradise: One Year on a Disappearing Island by Peter Rudiak-Gould

60. Animal Guides: In Life, Myth and Dreams by Neil Russack

61. PSYCH 107: Buddhist Psychology (iTunes U course) by Eleanor Rosch

62. The Ancient Library of Qumran by Frank Moore Cross

63. Consciousness at the Crossroads: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Brain Science and Buddhism by Dalai Lama

July 2013

64. Geography of World Cultures iTunes U course by Martin W. Lewis

65. Cosmos by Carl Sagan

66. A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

67. Daring to Embrace the Other: Franciscans and Muslims in Dialogue, ed. Daria Mitchell O.S.F.

68. Francis and Islam by J. Hoeberichts

69. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century by Thomas L. Friedman

70. Telling Tales by Neil Gaiman

71. The Beginner's Guide to Wicca: How to Practice Earth-Centered Spirituality by Starhawk

72. Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America by Barbara Ehrenreich

73. Josephus and the New Testament by Steve Mason

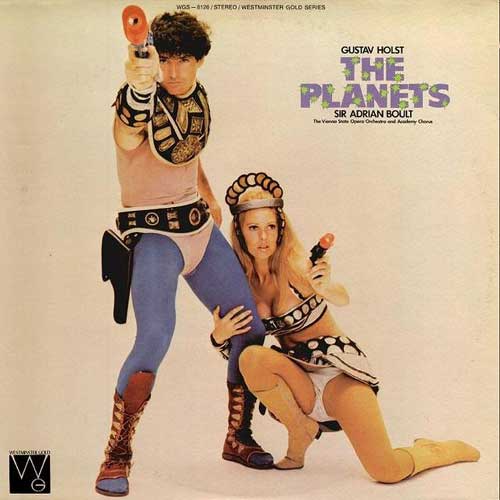

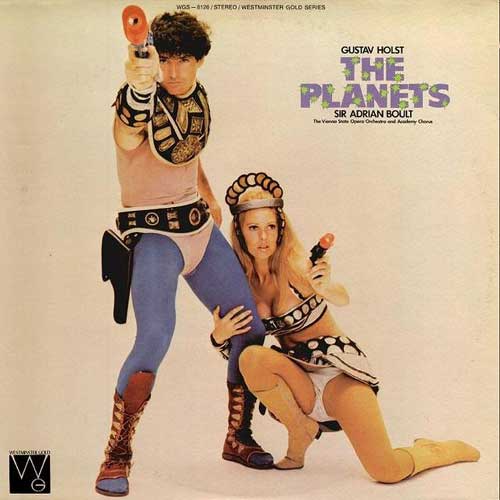

74. The Planets by Dava Sobel

75. Francis & His Brothers: A Popular History of the Franciscan Friars by Dominic V. Monti OFM

76. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

77. Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt by Barbara Mertz

78. Jonah: A Psycho-Religious Approach to the Prophet by Andre Lacocque

August 2013

79. Experience And Education by John Dewey

80. The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

81. What Were the Crusades? by Jonathan Riley-Smith

82. Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults) by Robert Barron

83. Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism by Rita M. Gross

84. The Way of the Heart: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers by Henri J. M. Nouwen

85. Arguing the Just War in Islam by John Kelsay

86. The Varieties of Scientific Experience by Carl Sagan

87. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America by James M. O'Toole

88. The New Concise History of the Crusades by Thomas F. Madden

89. Experiments in Ethics by Kwame Anthony Appiah

90. Altered Egos: How the Brain Creates the Self by Todd E. Feinberg

91. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

92. Francis of Assisi (The Great Courses) by William R. Cook

93. Against a Hindu God: Buddhist Philosophy of Religion in India by Parimal G. Patil

94. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

95. Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road by Johan Elverskog

96. The Era of the Crusades (Great Courses lectures) by Kenneth W. Harl

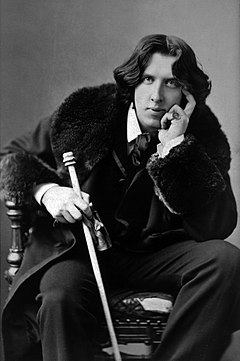

97. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

98. Islam by Ismail R. Al-Faruqi

99. The Great Courses: World Philosophy by Kathleen Higgins

100. Beyond Babel: A Handbook for Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages, ed. by John Kaltner and Steven L McKenzie

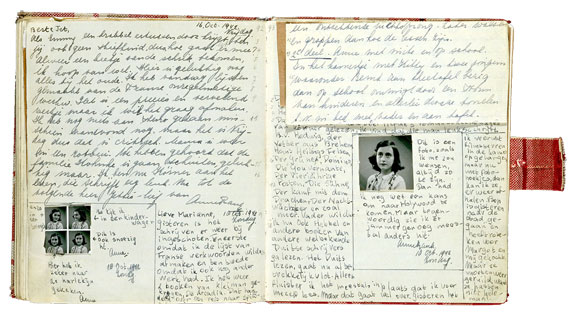

101. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

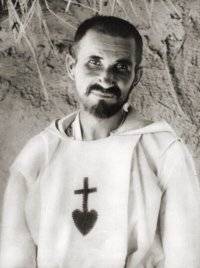

102. Christian Hermit in an Islamic World: A Muslim's View of Charles De Foucauld by Ali Merad

September 2013

103. Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America by Gustav Niebuhr

104. The Early Middle Ages, 284-1000 (Open Yale Courses) by Paul H. Freedman

105. The Hiding Place by Corrie Ten Boom

106. Dharma Punx by Noah Levine

107. Beowulf, trans. Benedict Flynn

108. Mortality by Christopher Hitchens

109. All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward

110. The Myth of Sanity: Divided Consciousness and the Promise of Awareness by Martha Stout

111. A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including their own Narratives of Emancipation by David W. Blight

112. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

113. Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious by Chris Stedman

114. A New Religious America: How a "Christian Country" Has Become the World's Most Religiously Diverse Nation by Diana L. Eck

115. Among the Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line by Jason Rosenhouse

I am changing my reading habits substantially. For one, I have fallen into the habit of reading light books so I can give them away. This is great for my TBR dent and my books-read quotient, but then I end up reading nothing but fluff. So I am scratching that idea.

I also have fallen into the habit of reading books and waiting a while to review them. This leads to bland reviews because the book is not fresh in my mind. Ho hum.

The list:

January 2013:

1. The Roman Empire and the New Testament: An Essential Guide (Essential Guides) by Warren Carter

2. The World is Charged: The Transcendent with Us by Francis R. Smith

3. The Critical Meaning of the Bible by Raymond E. Brown

4. The Anome by Jack Vance

5. The Christians as the Romans Saw Them by Robert Louis Wilken

6. An Introduction to Theology in Global Perspective by Stephen B. Bevans

7. The Sandman, Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes by Neil Gaiman

February 2013:

8. The Giver by Lois Lowry

9. The Book of Daniel (Cambridge Bible Commentaries on the Old Testament) by Raymond Hammer

10. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West by Donald S. Lopez Jr.

11. The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius

12. Megillat Esther by JT Waldman

13. Space Opera by Jack Vance

March 2013:

14. The British Discovery of Buddhism by Philip C. Almond

15. Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism by Miranda Shaw

16. King David by Kyle Baker

17. The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

18. Saints and Society: The Two Worlds of Western Christendom, 1000-1700 by Donald Weinstein

19. Autobiography of Charles Darwin

April 2013

20. My Life with the Saints by James Martin, S.J.

21. On Justice, Power, and Human Nature: The Essence of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

22. The Clouds by Aristophanes

23. Being Upright: Zen Meditation and the Bodhisattva Precepts by Reb Anderson

24. The Unconscious Christian: Images of God in Dreams (Jung and Spirituality) by James A. Hall

25. The Innocence of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton

26. The Diaries of Adam and Eve by Mark Twain

27. The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

28. The Life of Blessed Francis by Thomas of Celano

29. The Life of St. Francis of Assisi by St. Bonaventure

30. Lives of Roman Christian Women (Penguin Classics) by Carolinne White

31. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott

32. Minding God: Theology and the Cognitive Sciences by Gregory R. Peterson

33. Naturalism, Theism and the Cognitive Study of Religion: Religion Explained? by Aku Visala

34. The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin (read parts)

May 2013:

35. How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment by Eihei Dogen

36. Lilith, A Romance by George MacDonald

37. On Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and the Church in the Twenty-First Century by Jorge Mario Bergoglio and Abraham Skorka

38. Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine by Bart D. Ehrman

39. Daring to Cross the Threshold: Francis of Assisi Encounters Sultan Malek al-Kamil by Kathleen A. Warren

40. Saint Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter by John V. Tolan (partially read)

41. Collected Public Domain Works of H. P. Lovecraft by H. P. Lovecraft

42. Love's Executioner & Other Tales of Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom

43. The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins

44. The Selfish Genius: How Richard Dawkins Rewrote Darwin's Legacy by Fern Elsdon-Baker (partially read)

45. Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris

46. Welcome to the Episcopal Church: An Introduction to Its History, Faith, and Worship by Christopher L. Webber

47. How Biblical Languages Work: A Student's Guide to Learning Hebrew and Greek by Peter James Silzer

48. Dead Man Walking by Helen Prejean

49. The Dawkins Delusion?: Atheist Fundamentalism and the Denial of the Divine by Alister McGrath

50. Turning Suffering Inside Out by Darlene Cohen

51. The Nine Billion Names of God by Arthur C. Clarke

June 2013

52. When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet by Hildegard Diemberger

53. The Evolving God: Charles Darwin on the Naturalness of Religion by J. David Pleins

54. Charles Darwin: A Memorial Poem by George John Romanes

55. Islam & Franciscanism: A Dialogue (Spirit and Life Series Volume 9)

56. Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice by Thich Nhat Hanh

57. Introduction to Greek, 2/e by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine

58. Understanding Language: A Guide for Beginning Students of Greek & Latin by Donald Fairbairn

59. Surviving Paradise: One Year on a Disappearing Island by Peter Rudiak-Gould

60. Animal Guides: In Life, Myth and Dreams by Neil Russack

61. PSYCH 107: Buddhist Psychology (iTunes U course) by Eleanor Rosch

62. The Ancient Library of Qumran by Frank Moore Cross

63. Consciousness at the Crossroads: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Brain Science and Buddhism by Dalai Lama

July 2013

64. Geography of World Cultures iTunes U course by Martin W. Lewis

65. Cosmos by Carl Sagan

66. A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

67. Daring to Embrace the Other: Franciscans and Muslims in Dialogue, ed. Daria Mitchell O.S.F.

68. Francis and Islam by J. Hoeberichts

69. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century by Thomas L. Friedman

70. Telling Tales by Neil Gaiman

71. The Beginner's Guide to Wicca: How to Practice Earth-Centered Spirituality by Starhawk

72. Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America by Barbara Ehrenreich

73. Josephus and the New Testament by Steve Mason

74. The Planets by Dava Sobel

75. Francis & His Brothers: A Popular History of the Franciscan Friars by Dominic V. Monti OFM

76. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

77. Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt by Barbara Mertz

78. Jonah: A Psycho-Religious Approach to the Prophet by Andre Lacocque

August 2013

79. Experience And Education by John Dewey

80. The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

81. What Were the Crusades? by Jonathan Riley-Smith

82. Eucharist (Catholic Spirituality for Adults) by Robert Barron

83. Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism by Rita M. Gross

84. The Way of the Heart: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers by Henri J. M. Nouwen

85. Arguing the Just War in Islam by John Kelsay

86. The Varieties of Scientific Experience by Carl Sagan

87. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America by James M. O'Toole

88. The New Concise History of the Crusades by Thomas F. Madden

89. Experiments in Ethics by Kwame Anthony Appiah

90. Altered Egos: How the Brain Creates the Self by Todd E. Feinberg

91. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

92. Francis of Assisi (The Great Courses) by William R. Cook

93. Against a Hindu God: Buddhist Philosophy of Religion in India by Parimal G. Patil

94. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

95. Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road by Johan Elverskog

96. The Era of the Crusades (Great Courses lectures) by Kenneth W. Harl

97. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

98. Islam by Ismail R. Al-Faruqi

99. The Great Courses: World Philosophy by Kathleen Higgins

100. Beyond Babel: A Handbook for Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages, ed. by John Kaltner and Steven L McKenzie

101. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

102. Christian Hermit in an Islamic World: A Muslim's View of Charles De Foucauld by Ali Merad

September 2013

103. Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America by Gustav Niebuhr

104. The Early Middle Ages, 284-1000 (Open Yale Courses) by Paul H. Freedman

105. The Hiding Place by Corrie Ten Boom

106. Dharma Punx by Noah Levine

107. Beowulf, trans. Benedict Flynn

108. Mortality by Christopher Hitchens

109. All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward

110. The Myth of Sanity: Divided Consciousness and the Promise of Awareness by Martha Stout

111. A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including their own Narratives of Emancipation by David W. Blight

112. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

113. Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious by Chris Stedman

114. A New Religious America: How a "Christian Country" Has Become the World's Most Religiously Diverse Nation by Diana L. Eck

115. Among the Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line by Jason Rosenhouse

3JDHomrighausen

Dead Man Walking by Helen Prejean

Though this is probably best known as a movie, it was based on the true story of one nun's advocacy for Louisiana's death row inmates. Prejean, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph, was working in urban ministry in a poor section of New Orleans when a friend suggested her as a spiritual advisor for death row inmate Patrick Sonnier. Though she was repulsed by his crime and sometimes his character, her loving listening to his pain was enough to lead her into a greater awareness of the injustices of the death penalty.

For me, the death penalty is such an obvious bad idea that it hardly merits discussion. This makes it tough for me to explain to others why I think so. (Saying "Catholic social teaching" doesn't usually cut it.) Often I ask whether or not they would be willing to have the executioner's job. That usually gets less enthusiasm. This is essentially what Prejean finds. It's easy to be pro-death penalty when it's discussed in terms of deterrence arguments and financial convenience. Much harder when you are in a room watching someone be killed, or when you are with them in their last panicked hours.

Prejean didn't just face enemies in the political realm. She faced them in her own church. The book is riddled with descriptions of hypocrites in her own cloth: a bishop who advocates for the death penalty, death row chaplains who refer to the inmates as "scum," lay Catholics who write her letters castigating her for seeing Christ in murderers and rapists. She patiently points out that the death penalty is against Church teaching and flatly contradicts the pro-life agenda. To me the most horrifying part is the sexism: people telling her that nuns should be doing menial service work for the Church, meek and mild, not pursuing their own calls from God even if it means knocking some heads and ruffling some feathers to combat injustice. I really admire her for her ability to stand up to (and in this book, name) those who do not speak the truth.

The only downside of this tightly-written book is that some of the statistics are out of date or specific to Louisiana. But I doubt the realities have changed: the death row is still given to poor male racial minorities, it costs an exorbitant amount of money, etc. And after observing victims' families, Prejean argues that it fails to bring the closure many hope it will. (Another thing that seems obvious to me: vengeance won't bring healing.)

When this book came out, Prejean was roundly criticized from every angle. One journalist even alleged she had a romantic affair with one of the men she ministered to. Others alleged she co-opted the victims' families' stories for her own political advocacy, or that she failed to care about the families altogether. Yet in the book Prejean herself admits her biggest regret was not visiting the families of the victims sooner. She became close friends with two families of victims, one against the death penalty and the other a forceful advocate. Ultimately, her work is to bring about reconciliation and healing for everyone. Whether or not others understand that is not up to her.

The Nine Billion Names of God by Arthur C. Clarke

It's been too long since I read any good sci-fi. Thankfully a friend loaned me a big pile of it. I read 2001: A Space Odyssey a billion years ago (okay, 5-6) in high school. This collection of Clarke's favorite of his short stories did not disappoint.

The first thing that struck me about these is how different they were. Some were short vignettes conveying an emotion. Others were bizarre plot lines with unexpected or comedic endings. Many were set in space, but some were purely terrestrial.

Clarke conveys a sense of awe at the possible workings of the universe. The stories are plausible. One, "Encounter at Dawn," depicts a prehistorical meeting between humans and space aliens. It's certainly plausible, and that is enough to get my imagination going. The wide extremes of space and time his characters confront remind me of the little-ness of myself and my species. Clarke, like many science fiction writers, is great at showing people confronted with the utmost of their abilities and imagination.

Another thought that came up during the course of this book: not only are we limited by body and time, but excepting luminaries like Clarke, we are too culturally and species-ly narcissistic to truly accept and live in harmony with another race. If aliens truly did land on earth, we would probably never agree on how to interact with them as a species, and if we did it would probably be to kill and dissect them. Perhaps the aliens have already seen us and know we are not ready.

Anyway, enough randomness. My favorite stories in here were "Before Eden," "Encounter at Dawn," "Transience," and "The Star."

How Biblical Languages Work: A Student's Guide to Learning Hebrew and Greek by Peter James Silzer

I was hoping this book would help me tie together what I've learned in Hebrew and Greek, but it was at a much more basic level than I thought it would be. Having gone past the basic morphology and syntax of each language, this was not so helpful. But it was very readable and there were some good tidbits:

The possessive construction "the color of the car" in English actually comes from the Tyndale and KJV Bibles in the sixteenth century. Greek and especially Hebrew have possessive noun phrase construction that puts the possessor after the possessed. In English it's still more idiomatic to say "the car's color" but we have more options thanks to literal bible translations!

The authors discuss some universal principles of language that helped put things in context. For example, the universal polarity between fluid word order and rich morphology/inflections and strict word order with few inflections. Greek is very inflected, Hebrew less so, and English even less so. That's why both languages seem to have very loose and fuzzy syntax to my mind.

Some tips on how to look for Hebrew poetry. Hint: it's less about rhyme and meter (the sine qua nons of English poetry) and more about parallelism and use of figurative language.

Overall, I would give this to a friend just starting or in the first semester of Greek/Hebrew, but it lacks the depth for my level. Only one note: the transliteration of Greek and Hebrew into the English alphabet drove me nuts!

Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris

Since my Darwin and God class recently finished reading The God Delusion, it seemed reasonable to tackle Sam Harris' short exhortation to post-9/11 America. Since I've also ready Breaking the Spell, I can now say I've read three of the Four Horsemen!

Harris' book is thankfully not as sarcastic and mean as Dawkins'. His basic point is that fundamentalist/conservative Christians are blind to how much unjust violence their religion causes, and how selective and ridiculous it is to pretend to base our morality on an ancient text written by far more ethnocentric and tribalistic cultures. As an atheist, he is of course an advocate of secularism in the public and private sphere.

But what about those who are not his intended audience? What about liberal or progressive Christians? Harris writes that they are also guilty because they provide a cover of respectability for the crazy fundamentalists. That's frankly the worst argument I have ever heard. As a more liberal Christian, I am not responsible for what others of my creed think or believe. It's a shame Harris has this one very bad argument, because it eclipses some of the very good points Harris makes elsewhere about how Christians can be intolerant, bigoted, and bloodthirsty, despite Jesus' teaching.

As a side note, Harris has a Ph.D. in neuroscience, and I would love it if he took a different science-religion angle and participated in one of the Mind-Life dialogues with the Dalai Lama.

Though this is probably best known as a movie, it was based on the true story of one nun's advocacy for Louisiana's death row inmates. Prejean, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph, was working in urban ministry in a poor section of New Orleans when a friend suggested her as a spiritual advisor for death row inmate Patrick Sonnier. Though she was repulsed by his crime and sometimes his character, her loving listening to his pain was enough to lead her into a greater awareness of the injustices of the death penalty.

For me, the death penalty is such an obvious bad idea that it hardly merits discussion. This makes it tough for me to explain to others why I think so. (Saying "Catholic social teaching" doesn't usually cut it.) Often I ask whether or not they would be willing to have the executioner's job. That usually gets less enthusiasm. This is essentially what Prejean finds. It's easy to be pro-death penalty when it's discussed in terms of deterrence arguments and financial convenience. Much harder when you are in a room watching someone be killed, or when you are with them in their last panicked hours.

Prejean didn't just face enemies in the political realm. She faced them in her own church. The book is riddled with descriptions of hypocrites in her own cloth: a bishop who advocates for the death penalty, death row chaplains who refer to the inmates as "scum," lay Catholics who write her letters castigating her for seeing Christ in murderers and rapists. She patiently points out that the death penalty is against Church teaching and flatly contradicts the pro-life agenda. To me the most horrifying part is the sexism: people telling her that nuns should be doing menial service work for the Church, meek and mild, not pursuing their own calls from God even if it means knocking some heads and ruffling some feathers to combat injustice. I really admire her for her ability to stand up to (and in this book, name) those who do not speak the truth.

The only downside of this tightly-written book is that some of the statistics are out of date or specific to Louisiana. But I doubt the realities have changed: the death row is still given to poor male racial minorities, it costs an exorbitant amount of money, etc. And after observing victims' families, Prejean argues that it fails to bring the closure many hope it will. (Another thing that seems obvious to me: vengeance won't bring healing.)

When this book came out, Prejean was roundly criticized from every angle. One journalist even alleged she had a romantic affair with one of the men she ministered to. Others alleged she co-opted the victims' families' stories for her own political advocacy, or that she failed to care about the families altogether. Yet in the book Prejean herself admits her biggest regret was not visiting the families of the victims sooner. She became close friends with two families of victims, one against the death penalty and the other a forceful advocate. Ultimately, her work is to bring about reconciliation and healing for everyone. Whether or not others understand that is not up to her.

The Nine Billion Names of God by Arthur C. Clarke

It's been too long since I read any good sci-fi. Thankfully a friend loaned me a big pile of it. I read 2001: A Space Odyssey a billion years ago (okay, 5-6) in high school. This collection of Clarke's favorite of his short stories did not disappoint.

The first thing that struck me about these is how different they were. Some were short vignettes conveying an emotion. Others were bizarre plot lines with unexpected or comedic endings. Many were set in space, but some were purely terrestrial.

Clarke conveys a sense of awe at the possible workings of the universe. The stories are plausible. One, "Encounter at Dawn," depicts a prehistorical meeting between humans and space aliens. It's certainly plausible, and that is enough to get my imagination going. The wide extremes of space and time his characters confront remind me of the little-ness of myself and my species. Clarke, like many science fiction writers, is great at showing people confronted with the utmost of their abilities and imagination.

Another thought that came up during the course of this book: not only are we limited by body and time, but excepting luminaries like Clarke, we are too culturally and species-ly narcissistic to truly accept and live in harmony with another race. If aliens truly did land on earth, we would probably never agree on how to interact with them as a species, and if we did it would probably be to kill and dissect them. Perhaps the aliens have already seen us and know we are not ready.

Anyway, enough randomness. My favorite stories in here were "Before Eden," "Encounter at Dawn," "Transience," and "The Star."

How Biblical Languages Work: A Student's Guide to Learning Hebrew and Greek by Peter James Silzer

I was hoping this book would help me tie together what I've learned in Hebrew and Greek, but it was at a much more basic level than I thought it would be. Having gone past the basic morphology and syntax of each language, this was not so helpful. But it was very readable and there were some good tidbits:

The possessive construction "the color of the car" in English actually comes from the Tyndale and KJV Bibles in the sixteenth century. Greek and especially Hebrew have possessive noun phrase construction that puts the possessor after the possessed. In English it's still more idiomatic to say "the car's color" but we have more options thanks to literal bible translations!

The authors discuss some universal principles of language that helped put things in context. For example, the universal polarity between fluid word order and rich morphology/inflections and strict word order with few inflections. Greek is very inflected, Hebrew less so, and English even less so. That's why both languages seem to have very loose and fuzzy syntax to my mind.

Some tips on how to look for Hebrew poetry. Hint: it's less about rhyme and meter (the sine qua nons of English poetry) and more about parallelism and use of figurative language.

Overall, I would give this to a friend just starting or in the first semester of Greek/Hebrew, but it lacks the depth for my level. Only one note: the transliteration of Greek and Hebrew into the English alphabet drove me nuts!

Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris

Since my Darwin and God class recently finished reading The God Delusion, it seemed reasonable to tackle Sam Harris' short exhortation to post-9/11 America. Since I've also ready Breaking the Spell, I can now say I've read three of the Four Horsemen!

Harris' book is thankfully not as sarcastic and mean as Dawkins'. His basic point is that fundamentalist/conservative Christians are blind to how much unjust violence their religion causes, and how selective and ridiculous it is to pretend to base our morality on an ancient text written by far more ethnocentric and tribalistic cultures. As an atheist, he is of course an advocate of secularism in the public and private sphere.

But what about those who are not his intended audience? What about liberal or progressive Christians? Harris writes that they are also guilty because they provide a cover of respectability for the crazy fundamentalists. That's frankly the worst argument I have ever heard. As a more liberal Christian, I am not responsible for what others of my creed think or believe. It's a shame Harris has this one very bad argument, because it eclipses some of the very good points Harris makes elsewhere about how Christians can be intolerant, bigoted, and bloodthirsty, despite Jesus' teaching.

As a side note, Harris has a Ph.D. in neuroscience, and I would love it if he took a different science-religion angle and participated in one of the Mind-Life dialogues with the Dalai Lama.

4rebeccanyc

Glad to see your new thread with your new (real) name. By the way, for the future, you can edit the name of a continuation thread so you could have changed your name in it if you had done a continuation thread (that's how people can add Part II or whatever, but you can actually edit the title, but only when you start your new thread). However, you couldn't' start a continuation threadbecause LT doesn't give you that option until you reach 200 posts. Clear as mud?

Very interesting to read about Prejean. I have long been against the death penalty, although obviously not because of Catholic teaching! And interesting to read about the Greek and Hebrew language book: do you think it makes sense to combine them in one book? Are they sufficiently similar?

Very interesting to read about Prejean. I have long been against the death penalty, although obviously not because of Catholic teaching! And interesting to read about the Greek and Hebrew language book: do you think it makes sense to combine them in one book? Are they sufficiently similar?

5NanaCC

I really liked your review of Dead Man Walking. How many times have we heard about someone released from jail after x number of years, because new evidence has shown they could not have committed the crime. For me, that is a big reason to be against the death penalty.

6avidmom

That was all very interesting.

"species-ly narcissistic" HA!

vengeance won't bring healing

So true.

"species-ly narcissistic" HA!

vengeance won't bring healing

So true.

7baswood

Excellent review of Dead Man Walking. The barbarity of the death penalty is something that beggars belief in the so-called civilized West and so I think I would enjoy this book. I will also get into those Arthur C Clarke short stories soon,

8mkboylan

Funny I should read that review the same day I ran across this: Forgiving Dead Man Walking by Debbie Morris. I know nothing about it, just thought I'd toss it in here.

9JDHomrighausen

> 4

200 messages! Eeee gad! That's too many. I wouldn't want my page to get so muddled.

Greek and Hebrew are not much alike. They are from different language families entirely. That's a blessing and a boon: they are often studied together (seminary), and they won't be confused, but that also means one won't help you learn the other much like Greek and Latin do with each other.

> 8

I saw that book! Morris was critical of Prejean, in fact very hurt by her. Until this:

""This time though, I wasn't angry at Robert Lee Willie and Joseph Jesse Vaccaro," Morris said. "I was angry with Sister Helen Prejean. I was angry with Tim Robbins. I was angry with Susan Sarandon. I was angry with Sean Penn."

This time, the quiet victim broke her silence to confront Willie's spiritual adviser.

"When she answered the phone, I said 'Sister Helen, I don't know if you will recognize my name, but you will know me as the 16-year-old-girl from Madisonville,' and there was this silence," Morris said. "She said 'I've prayed for you so many times' and I knew then instantly, this is going to be ok.""

http://www.wbir.com/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=105968

Morris has become a big supporter of Prejean.

200 messages! Eeee gad! That's too many. I wouldn't want my page to get so muddled.

Greek and Hebrew are not much alike. They are from different language families entirely. That's a blessing and a boon: they are often studied together (seminary), and they won't be confused, but that also means one won't help you learn the other much like Greek and Latin do with each other.

> 8

I saw that book! Morris was critical of Prejean, in fact very hurt by her. Until this:

""This time though, I wasn't angry at Robert Lee Willie and Joseph Jesse Vaccaro," Morris said. "I was angry with Sister Helen Prejean. I was angry with Tim Robbins. I was angry with Susan Sarandon. I was angry with Sean Penn."

This time, the quiet victim broke her silence to confront Willie's spiritual adviser.

"When she answered the phone, I said 'Sister Helen, I don't know if you will recognize my name, but you will know me as the 16-year-old-girl from Madisonville,' and there was this silence," Morris said. "She said 'I've prayed for you so many times' and I knew then instantly, this is going to be ok.""

http://www.wbir.com/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=105968

Morris has become a big supporter of Prejean.

10JDHomrighausen

Charles Darwin: A Memorial Poem by George John Romanes

The Evolving God: Charles Darwin on the Naturalness of Religion by J. David Pleins

Perhaps the most intellectually engaging class I have taken this quarter is my "Darwin and God" course. We've dived into both theology, science, the evolution of morals, Darwin's personal religious beliefs, and a myriad of other fascinating beliefs. One enduring conclusion from the class is that the Victorian conflict between science and religion was hardly as sharp as simple caricatures such as Dawkins' would have us believe now. Both of these books examine the complexities of religion in the life of Darwin and his inner circle.

Romanes was a friend of Darwin's for the last decade of the latter's life and a fellow naturalist and scientific protege of the elderly and famous man. This poem was written over the period of a year or so after Darwin's death. Romanes evokes the grief of losing a great friend, chronicling his piercing grief during Darwin's funeral at Westminster Abbey. He hopes for an afterlife, juxtaposing his scientific reason with his deeper intimations of something beyond. He cries out to God for all the evil in the world of human and animal affairs, resolving his conflict in seeing how good comes out of the world's evil. Only someone truly sensitive to poetic language and scientific rationalism could have written such a deep poem.

Romanes' public persona was that of a skeptic, so it's little surprise that this lengthy cycle of 127 poems has been left unexamined and unpublished until now. Romanes was known as a poet. Bits of this have appeared in print before. But my professor, J. David Pleins, is editing this lengthy memorial poem for publication. Romanes has been overlooked in favor of other members of Darwin's circle such as Huxley and Wallace. After 100 years, perhaps Romanes will get his moment in the sun.

Pleins continues to examine Darwin's ideas of religion in his concise and even-handed look at Darwin's religious quest. Far from being a tortured soul caught in the crossfire of the 'eternal warfare of science and religion,' Darwin seemed to be at peace with his agnosticism in religious matters. Nor were his views easily categorized. Darwin was an evolving thinker too. He lost belief in the Bible as revelation at a young age. He explicitly challenged religion in his scientific works, especially traditional Christianity's deep split between humanity and the other creatures. But he also admitted privately that he had a hard time believing that the complexity of the world came about through chance and natural selection alone. Unlike many nonbelievers today, Darwin also appreciated religion's ability to effect peoples' greatest moral goodness. Darwin even began asking some of the first questions in evolutionary psychology of religion, over 100 years before that field existed in psychology.

Romanes and Darwin were both men who kept their spiritual leanings more private. Pro-religious ideas were sometimes could make one lose credibility in skeptical scientific circles. Anti-religious ideas could ruin one's moral - and intellectual - credibility in other groups. Keeping a sharp distinction between public and private thoughts enabled them to put up one public face while admitting their inclinations, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities in another. Hence Romanes' book of skeptical philosophy, A Candid Examination of Theism, was published under the name "Physicus." But nowadays, such anonymity is not plausible. It's harder to be a work-in-progress in the public eye, especially when one's reputation is at stake. I suspect this leads to much of the posturing that goes on in the science-religion debates. Dawkins is the posturer par excellence. He will not budge, and neither will his fundamentalist debaters.

Last but not least, it's consoling to see that Darwin himself addressed questions of religion with great depth and ability to change his mind. Those claiming Darwin for the banner of militant atheism would do well to read Pleins' book - when it comes out this summer!

The Evolving God: Charles Darwin on the Naturalness of Religion by J. David Pleins

Perhaps the most intellectually engaging class I have taken this quarter is my "Darwin and God" course. We've dived into both theology, science, the evolution of morals, Darwin's personal religious beliefs, and a myriad of other fascinating beliefs. One enduring conclusion from the class is that the Victorian conflict between science and religion was hardly as sharp as simple caricatures such as Dawkins' would have us believe now. Both of these books examine the complexities of religion in the life of Darwin and his inner circle.

Romanes was a friend of Darwin's for the last decade of the latter's life and a fellow naturalist and scientific protege of the elderly and famous man. This poem was written over the period of a year or so after Darwin's death. Romanes evokes the grief of losing a great friend, chronicling his piercing grief during Darwin's funeral at Westminster Abbey. He hopes for an afterlife, juxtaposing his scientific reason with his deeper intimations of something beyond. He cries out to God for all the evil in the world of human and animal affairs, resolving his conflict in seeing how good comes out of the world's evil. Only someone truly sensitive to poetic language and scientific rationalism could have written such a deep poem.

Romanes' public persona was that of a skeptic, so it's little surprise that this lengthy cycle of 127 poems has been left unexamined and unpublished until now. Romanes was known as a poet. Bits of this have appeared in print before. But my professor, J. David Pleins, is editing this lengthy memorial poem for publication. Romanes has been overlooked in favor of other members of Darwin's circle such as Huxley and Wallace. After 100 years, perhaps Romanes will get his moment in the sun.

Pleins continues to examine Darwin's ideas of religion in his concise and even-handed look at Darwin's religious quest. Far from being a tortured soul caught in the crossfire of the 'eternal warfare of science and religion,' Darwin seemed to be at peace with his agnosticism in religious matters. Nor were his views easily categorized. Darwin was an evolving thinker too. He lost belief in the Bible as revelation at a young age. He explicitly challenged religion in his scientific works, especially traditional Christianity's deep split between humanity and the other creatures. But he also admitted privately that he had a hard time believing that the complexity of the world came about through chance and natural selection alone. Unlike many nonbelievers today, Darwin also appreciated religion's ability to effect peoples' greatest moral goodness. Darwin even began asking some of the first questions in evolutionary psychology of religion, over 100 years before that field existed in psychology.

Romanes and Darwin were both men who kept their spiritual leanings more private. Pro-religious ideas were sometimes could make one lose credibility in skeptical scientific circles. Anti-religious ideas could ruin one's moral - and intellectual - credibility in other groups. Keeping a sharp distinction between public and private thoughts enabled them to put up one public face while admitting their inclinations, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities in another. Hence Romanes' book of skeptical philosophy, A Candid Examination of Theism, was published under the name "Physicus." But nowadays, such anonymity is not plausible. It's harder to be a work-in-progress in the public eye, especially when one's reputation is at stake. I suspect this leads to much of the posturing that goes on in the science-religion debates. Dawkins is the posturer par excellence. He will not budge, and neither will his fundamentalist debaters.

Last but not least, it's consoling to see that Darwin himself addressed questions of religion with great depth and ability to change his mind. Those claiming Darwin for the banner of militant atheism would do well to read Pleins' book - when it comes out this summer!

11rebeccanyc

#9 Most threads go at least 200 posts -- that doesn't seem that long to me! Thanks for the info about Greek and Hebrew; that's what I thought, but I wasn't thinking about the benefits of learning them together, or why people might.

12mkboylan

9 - Thanks for posting that link. So amazing.

and - another wonderful review - 10 - that made me think.

and - another wonderful review - 10 - that made me think.

13janeajones

Thoughtful post on Darwin. The memorial poem by Romanes sounds fascinating -- when does it go to print?

14JDHomrighausen

> 13

If all goes as planned, his edition will hit the press sometime next summer. Publishing takes forever!

If all goes as planned, his edition will hit the press sometime next summer. Publishing takes forever!

15JDHomrighausen

When A Woman Becomes A Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagma of Tibet by Hildegard Diemberger

Diemberger's dense and well-researched book explores the life of Chokyi Dronma, the first and most important lineage of female lamas in Tibet. Some background: Tibetan Buddhism is unique in that its lineages - leaders of schools of Buddhism, abbots of monasteries, etc. - are not done by choosing a successor or by passing the power onto one's child, but by finding the reincarnation of the lama who has died. This centuries-old practice is how, for example, we got the Dalai Lama. According to Tibetan belief, he is the fourteenth reincarnation of the same bodhisattva, in this case an incarnation of the celestial bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Like any other mode of passing on authority, lineage by reincarnation is subject to manipulation. Diemberger, an anthropologist at Cambridge, focuses on how these politics - especially gender politics - play out in the biography of fifteenth-century lineage founder Chokyi Dronma.

Chokyi Dronma herself was a Tibetan princess who, after the death of her only child, left behind her husband and his despised family to pursue a life devoted to the dharma. At first her husband would not let her leave, but she shaved her head - some say she scalped herself - and her possibly-insane devotion persuaded him. In time she came to be recognized as an incarnation of Dorje Pagmo (aka Vajrayogini), one of the most important female deities in Mahayana Buddhism. She studied under lama Chogye Namgyal and used her great royal wealth to act as a great patrons of the arts and sciences during the time of what Diemberger calls a "Tibetan Renaissance."

Soon after her death, her disciple Thangtong Gyalpo wrote her biography. Diemberger argues that he wrote it to legitimate the search for her successor, as the biography is full of references to how Chokyi Dronma was like Vajrayogini and how her rebirth lineage was prophecied during her life. Most tantalizingly, the end of the book is lost. Dronma was about to ascend Tsari Mountain, a holy site forbidden to women, which leads Diemberger to suggest that the end was censored because it flouted religious convention.

This is the fourth in my category of books written by or about women. Somehow this category turned into "women and religion." I'm beginning to see some commonalities in how women are depicted in the three religious traditions I am reading around. I see the most affinities here with the contents of Lives of Roman Christian Women.

First - the theme of insanity. Dronma had to feign insanity to make others take her religious devotion seriously. This seems to be something women have to do in different religious traditions, perhaps because their agency would not be taken seriously otherwise. When St. Jerome writes about his patron Paula the Elder, he cites her abandonment of her children - surely insane - as proof of her great devotion to God. In early Christianity as in Tibet, women had more obstacles to renunciation, and had to be more drastic in proving their desire.

Like Paula the Elder, Chokyi Dronma was born into the elite, and her fame as a patroness would not have been possible had she not had a lot of money to give away. Elitism rears its ugly head. One of the projects she sponsored were a series of iron suspension bridges around Tibet, build by tantric master and civil engineer Thangthong Gyalpo. Some of these still stand, supposedly made of an alloy resistant to rust:

Last but not least, the problem of finding women's' voices in history. Chokyi Dronma's biography was written one of her male disciples. Most of the texts in Lives of Roman Christian Women were written by men. Even when they are esteemed, womens' own voices are often lost to history. I am suspicious of efforts to uncover these voices, such as Miranda Shaw's, as they often seem to be inventing just as much as uncovering. The Red Tent provided a much better model, a way of imagining women's' voices and roles in history using fiction. Thankfully, Diemberger has one way of overcoming this problem: the fact that the Dorje Phagmo lineage is still alive and well in Tibet, as is her famous Samding monastery, rebuilt after its destruction in the Cultural Revolution. Diemberger does a great job of bringing the book back to the present and the continuing enigma of Dorje Phagmo.

Diemberger's dense and well-researched book explores the life of Chokyi Dronma, the first and most important lineage of female lamas in Tibet. Some background: Tibetan Buddhism is unique in that its lineages - leaders of schools of Buddhism, abbots of monasteries, etc. - are not done by choosing a successor or by passing the power onto one's child, but by finding the reincarnation of the lama who has died. This centuries-old practice is how, for example, we got the Dalai Lama. According to Tibetan belief, he is the fourteenth reincarnation of the same bodhisattva, in this case an incarnation of the celestial bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Like any other mode of passing on authority, lineage by reincarnation is subject to manipulation. Diemberger, an anthropologist at Cambridge, focuses on how these politics - especially gender politics - play out in the biography of fifteenth-century lineage founder Chokyi Dronma.

Chokyi Dronma herself was a Tibetan princess who, after the death of her only child, left behind her husband and his despised family to pursue a life devoted to the dharma. At first her husband would not let her leave, but she shaved her head - some say she scalped herself - and her possibly-insane devotion persuaded him. In time she came to be recognized as an incarnation of Dorje Pagmo (aka Vajrayogini), one of the most important female deities in Mahayana Buddhism. She studied under lama Chogye Namgyal and used her great royal wealth to act as a great patrons of the arts and sciences during the time of what Diemberger calls a "Tibetan Renaissance."

Soon after her death, her disciple Thangtong Gyalpo wrote her biography. Diemberger argues that he wrote it to legitimate the search for her successor, as the biography is full of references to how Chokyi Dronma was like Vajrayogini and how her rebirth lineage was prophecied during her life. Most tantalizingly, the end of the book is lost. Dronma was about to ascend Tsari Mountain, a holy site forbidden to women, which leads Diemberger to suggest that the end was censored because it flouted religious convention.

This is the fourth in my category of books written by or about women. Somehow this category turned into "women and religion." I'm beginning to see some commonalities in how women are depicted in the three religious traditions I am reading around. I see the most affinities here with the contents of Lives of Roman Christian Women.

First - the theme of insanity. Dronma had to feign insanity to make others take her religious devotion seriously. This seems to be something women have to do in different religious traditions, perhaps because their agency would not be taken seriously otherwise. When St. Jerome writes about his patron Paula the Elder, he cites her abandonment of her children - surely insane - as proof of her great devotion to God. In early Christianity as in Tibet, women had more obstacles to renunciation, and had to be more drastic in proving their desire.

Like Paula the Elder, Chokyi Dronma was born into the elite, and her fame as a patroness would not have been possible had she not had a lot of money to give away. Elitism rears its ugly head. One of the projects she sponsored were a series of iron suspension bridges around Tibet, build by tantric master and civil engineer Thangthong Gyalpo. Some of these still stand, supposedly made of an alloy resistant to rust:

Last but not least, the problem of finding women's' voices in history. Chokyi Dronma's biography was written one of her male disciples. Most of the texts in Lives of Roman Christian Women were written by men. Even when they are esteemed, womens' own voices are often lost to history. I am suspicious of efforts to uncover these voices, such as Miranda Shaw's, as they often seem to be inventing just as much as uncovering. The Red Tent provided a much better model, a way of imagining women's' voices and roles in history using fiction. Thankfully, Diemberger has one way of overcoming this problem: the fact that the Dorje Phagmo lineage is still alive and well in Tibet, as is her famous Samding monastery, rebuilt after its destruction in the Cultural Revolution. Diemberger does a great job of bringing the book back to the present and the continuing enigma of Dorje Phagmo.

16JDHomrighausen

Zen Keys by Thich Nhat Hanh

Hanh is a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, currently living in France, and perhaps one of the most well-known writers on Buddhism in English. Hanh has been transmitting the dharma to the West for some decades now, and this was one of his first books for a Western audience.

This book is a tad eclectic. The first three chapters discuss basics of Zen practice including koans. The end of the book is a lengthy collection of koans for use. But in the middle of the book there is long, confusing chapter on Buddhist philosophy that I couldn't get through. The most interesting chapter for me was "The Regeneration of Humanity," where he discusses how Buddhism will go to the West:

"The East, although poor, has not suffered from the levels of fanaticism and violence that the West has. … But the majority of Westerners do not possess this virtue of modesty in their approach to the East. They are satisfied with their methodology and their principles, and they remain attached to criteria and values of their own civilization while desiring to know the East."

I'm not sure I would describe the East as having been less fanatic. Since this came out in 1974, I also think more Westerners practicing Buddhism really diving into its Asian roots, and in a way that goes beyond merely describing everything in Asia as "the East," as if it's all the same. But since this was written in 1974, at the start of his writing career, it's not as clear or interesting as some of his later stuff that I've read. An okay book, but not Hanh's best.

Hanh is a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, currently living in France, and perhaps one of the most well-known writers on Buddhism in English. Hanh has been transmitting the dharma to the West for some decades now, and this was one of his first books for a Western audience.

This book is a tad eclectic. The first three chapters discuss basics of Zen practice including koans. The end of the book is a lengthy collection of koans for use. But in the middle of the book there is long, confusing chapter on Buddhist philosophy that I couldn't get through. The most interesting chapter for me was "The Regeneration of Humanity," where he discusses how Buddhism will go to the West:

"The East, although poor, has not suffered from the levels of fanaticism and violence that the West has. … But the majority of Westerners do not possess this virtue of modesty in their approach to the East. They are satisfied with their methodology and their principles, and they remain attached to criteria and values of their own civilization while desiring to know the East."

I'm not sure I would describe the East as having been less fanatic. Since this came out in 1974, I also think more Westerners practicing Buddhism really diving into its Asian roots, and in a way that goes beyond merely describing everything in Asia as "the East," as if it's all the same. But since this was written in 1974, at the start of his writing career, it's not as clear or interesting as some of his later stuff that I've read. An okay book, but not Hanh's best.

17avidmom

>9 JDHomrighausen: The link to the Morris interview gave me goosebumps for both bad and good reasons. Thanks for that.

>15 JDHomrighausen: All of that is fascinating! Thanks for including the picture of the bridge.

There's always so much to learn on your thread!!!!

>15 JDHomrighausen: All of that is fascinating! Thanks for including the picture of the bridge.

There's always so much to learn on your thread!!!!

19baswood

Jonathan, very interesting stuff on Darwin, who has always appeared to me as typical of his times, with his ability almost to compartmentalise his beliefs and his scientific research. I also enjoyed your thoughts on When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty

20JDHomrighausen

Thanks for all your comments!

Sadly, many of the bridges are gone, washed away by floods or destroyed to make room for newer bridges. It's amazing that bridges still stand after 500+ years. Still, I'm not sure I'd want to walk on them!!

Sadly, many of the bridges are gone, washed away by floods or destroyed to make room for newer bridges. It's amazing that bridges still stand after 500+ years. Still, I'm not sure I'd want to walk on them!!

21rebeccanyc

I love the bridge too, and continue to enjoy learning about diverse topics on your thread.

22JDHomrighausen

Thank you for your kind comments.

Things over here are winding to an end. Being a humanities major, I have final papers instead of tests, and once those are well on the way to fruition I start relaxing well before the science majors cramming for their finals.

I'm especially glad that in less than a week, I will have finished my first year of Attic Greek. I'm looking forward to feeling like I can tackle anything, opening an actual text, then realizing how little I actually know. A good slap in the face.

Also, I know this sounds nuts, but I am looking forward to fall classes. :)

Things over here are winding to an end. Being a humanities major, I have final papers instead of tests, and once those are well on the way to fruition I start relaxing well before the science majors cramming for their finals.

I'm especially glad that in less than a week, I will have finished my first year of Attic Greek. I'm looking forward to feeling like I can tackle anything, opening an actual text, then realizing how little I actually know. A good slap in the face.

Also, I know this sounds nuts, but I am looking forward to fall classes. :)

23rebeccanyc

What will you do over the summer, Jonathan?

24JDHomrighausen

Rebecca - I am reading over the summer. And that's really it. Thank goodness. I am also going to be practicing the languages I am learning - including picking up a fourth, medieval Latin, which sounds hard but once you've gone Greek, Latin is a piece of cake. (The people in my Greek class who have done Latin are all going through the class like it's easy breezy.)

26JDHomrighausen

It has a lot of the same structures as Greek, so once you have learned to think in Greek, you can think in Latin. Also Medieval Latin is (I hear) easier than Classical. But we will see, maybe it will crush me...

27dchaikin

Catching up with the new thread. So much here in these first two dozen posts. The Dead Man Walking and Morris info was really sad and moving. The Darwin stuff absolutely fascinating. I have a reflexive thought that it's curious that religious thought still spends so much time on Darwin since he is hardly cutting edge. But he was a fascinating character. I have a two volume biography sitting on my overwhelming TBR shelves. And the Buddhist stuff is always interesting.

Enjoy your summer!

Enjoy your summer!

28mkboylan

Have you looked at your Islam and Franciscanism yet? Comments?

29JDHomrighausen

> 27

Dan, of course every movement needs a figurehead, even if they were neither entirely original nor developed all the insights we have now. So while Darwin didn't come up with the idea of species change over time, and he didn't know a thing about genetics, he is still the poster-boy of evolution and all that it represents. One of my professor's points is that we often project current science vs. religion conflict on Darwin, just as perhaps we project an entire scientific revolution onto him. While he is unique, he's not exactly a Nietzschean Ubermensch, making an entirely field from nothing!

> 28

It actually was not as exciting as I thought it would be. A few essays were worth reading, and I will post about them within a few days. I have three final papers yet to finish so book reviews will have to wait!

But - I have been reading about Francis and Islam for a month or so now - the best books I have found are Francis and Islam by J. Hoeberichts (a former Franciscan, now married theologian, taught for many years in Pakistan) and Saint Francis and the Sultan by John Tolan for a historian's portrait of how the event has been painted in the last ~800 years. Of course, the best place to start is with the first hagiography of Francis (Thomas of Celano) and the most important (Bonaventure).

Dan, of course every movement needs a figurehead, even if they were neither entirely original nor developed all the insights we have now. So while Darwin didn't come up with the idea of species change over time, and he didn't know a thing about genetics, he is still the poster-boy of evolution and all that it represents. One of my professor's points is that we often project current science vs. religion conflict on Darwin, just as perhaps we project an entire scientific revolution onto him. While he is unique, he's not exactly a Nietzschean Ubermensch, making an entirely field from nothing!

> 28

It actually was not as exciting as I thought it would be. A few essays were worth reading, and I will post about them within a few days. I have three final papers yet to finish so book reviews will have to wait!

But - I have been reading about Francis and Islam for a month or so now - the best books I have found are Francis and Islam by J. Hoeberichts (a former Franciscan, now married theologian, taught for many years in Pakistan) and Saint Francis and the Sultan by John Tolan for a historian's portrait of how the event has been painted in the last ~800 years. Of course, the best place to start is with the first hagiography of Francis (Thomas of Celano) and the most important (Bonaventure).

31JDHomrighausen

Greetings librarything inhabitants,

Well, the end has come. I finished my final final ... only to be told by next year's roommate that he doesn't want to live with me. (I am still not sure what he is thinking.) So I called some apartment complexes, visited one place, found it perfect, and within 24 hours of deciding I was going to live off-campus I had secured a place and had my credit approved.

The odds are in my favor.

Also, I have ~20-25 boxes of books total.

Well, the end has come. I finished my final final ... only to be told by next year's roommate that he doesn't want to live with me. (I am still not sure what he is thinking.) So I called some apartment complexes, visited one place, found it perfect, and within 24 hours of deciding I was going to live off-campus I had secured a place and had my credit approved.

The odds are in my favor.

Also, I have ~20-25 boxes of books total.

32avidmom

>31 JDHomrighausen: Oh! A space of one's own. Total awesomeness.

I remember living all by myself (well, not all by myself, I had a cat) in my first (and only) studio apartment.

Hope you have friends willing to help you move - boxes and all. :-)

I remember living all by myself (well, not all by myself, I had a cat) in my first (and only) studio apartment.

Hope you have friends willing to help you move - boxes and all. :-)

33JDHomrighausen

Good news over in my world. So summer is officially underway. I have a job at the university library, but it's a job with a lot of downtime, so I have a lot of time to read and study. I'm not doing any summer courses, so it's great to be able to do what I want to do.

I recently finished listening to Eleanor Rosch's Buddhist Psychology course on iTunes U. It's titled "Buddhist Psychology" rather than "Psychology of Buddhism" because the course spends most of its time on Buddhist meditation and views of the mind. But the few lectures on Western research were fascinating too. I am reading Buddhist philosopher David Kalupahana's book Principles of Buddhist Psychology and the Mind-Life dialogues Consciousness at the Crossroads to go along with it.

Also listening to Martin W. Lewis' iTunes U course on Geography of World Cultures. It covers the main linguistic and religious regions of the world, giving more background information on various cultures than I have ever heard before. For example, on native North American languages: California has had eighteen native American languages, most of which (like most native American languages) are either extinct or moribund. One exception to this continent-wide trend is Navajo, which enjoys some 170-180k speakers and is in no danger of dying out.

(Language extinction makes me sad. Especially Aramaic, the language of Jesus.)

I recently finished listening to Eleanor Rosch's Buddhist Psychology course on iTunes U. It's titled "Buddhist Psychology" rather than "Psychology of Buddhism" because the course spends most of its time on Buddhist meditation and views of the mind. But the few lectures on Western research were fascinating too. I am reading Buddhist philosopher David Kalupahana's book Principles of Buddhist Psychology and the Mind-Life dialogues Consciousness at the Crossroads to go along with it.

Also listening to Martin W. Lewis' iTunes U course on Geography of World Cultures. It covers the main linguistic and religious regions of the world, giving more background information on various cultures than I have ever heard before. For example, on native North American languages: California has had eighteen native American languages, most of which (like most native American languages) are either extinct or moribund. One exception to this continent-wide trend is Navajo, which enjoys some 170-180k speakers and is in no danger of dying out.

(Language extinction makes me sad. Especially Aramaic, the language of Jesus.)

34JDHomrighausen

P.S. I have eight bookcases up in my new apartment....!!

35avidmom

>34 JDHomrighausen: LOL! Eight very big bookcases I hope :)

(Language extinction makes me sad. Especially Aramaic, the language of Jesus.)

That's the one thing I liked about the movie, the PTSD inducing "The Passion of the Christ" was hearing the Aramaic (or I guess as close to it as possible).

(Language extinction makes me sad. Especially Aramaic, the language of Jesus.)

That's the one thing I liked about the movie, the PTSD inducing "The Passion of the Christ" was hearing the Aramaic (or I guess as close to it as possible).

36rebeccanyc

Language extinction is a very interesting topic. I once read a good book about it called Spoken Here: Travels among Threatened Languages that might interest you. Did you know that during, World War II, the US military used Navajo speakers as "code talkers" because nobody else could understand their language? This is the home page for the Code Talker organization and this is a Wikipedia article about code talkers in general.

37JDHomrighausen

> 36

I have heard of that, but didn't know they had a website! I don't know if the code-talking is related to Navajo's survival in the face of mass extinction of native American languages. I imagine it has at least given the Navajo pride in their language and more incentive to pass it down.

I have heard of that, but didn't know they had a website! I don't know if the code-talking is related to Navajo's survival in the face of mass extinction of native American languages. I imagine it has at least given the Navajo pride in their language and more incentive to pass it down.

38JDHomrighausen

Rebecca and Ms. Mom -

This is the article that got me interested in Aramaic. I will be learning it at some point so this is whetting my appetite!

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/ideas-innovations/How-to-Save-a-Dying-Language-187...

This is the article that got me interested in Aramaic. I will be learning it at some point so this is whetting my appetite!

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/ideas-innovations/How-to-Save-a-Dying-Language-187...

39janeajones

Congratulations on your new digs, bookcases and job -- sounds like a promising summer!

40rebeccanyc

Thanks for the link, and congratulations on your new bookcases, which I forgot to mention before!

41solla

I have only recently returned to Club Read, so I'm slowly sampling threads and just came on yours. I enjoyed your review of Dead Man Walking. I saw the movie but haven't read the book and it sounds like an interesting read. About capital punishment it seems obvious to me that if you consider murder wring, and that killing someone is not something for humans to decide, then the death penalty is out, aside from all the other issues of how unfairly it is applied.

42JDHomrighausen

if you consider murder wring, and that killing someone is not something for humans to decide...

There are exceptions. What if you live in a hunter-gatherer society? There aren't any jails available. But in America, I see no motivation other than unhealthy vengeance.

There are exceptions. What if you live in a hunter-gatherer society? There aren't any jails available. But in America, I see no motivation other than unhealthy vengeance.

43JDHomrighausen

The Ancient Library of Qumran by Frank Moore Cross

Cross' book, first published in 1959 when the Dead Sea Scrolls were a new discovery, has been rewritten in this 1990s edition. It provides an overview of the manuscript finds and how they impact biblical studies as a whole. Though it is too scholarly for the general reader, too jam packed with footnotes, it has some high points.

A professor told me to read this book as background for the research she is doing with one of the DSS manuscripts, the minor prophets scroll. While I read the chapter on Old Testament textual criticism, the most interesting section for me was that on Essenes and primitive Christianity. Though the Essenes were not Christian, there are a lot of parallels: both are apocalyptic communities, both believe they live in the last age, both see their religious movement as the fulfillment of past prophecy. Like Paul, the Essenes eschewed marriage. (Why bother marrying when the world will end soon?) Both were tightly-knit communities with little or no sense of private property.

Most interesting to me is Cross' theory of the origins of the Essenes. He argues that a dispute between priestly factions led to the losing side leaving society and founding the true priesthood in the wilderness. The "righteous teacher" spoken of frequently in Essene literature is that priest. Another frequently-mentioned but never-identified figure, the "Wicked One," is the head priest of the winning faction. A fascinating theory, though one with little support.

Cross' book was a good quick read, but far too bogged down in technical details to make a good introduction. It seems to have been written more for scholars than for the public.

Surviving Paradise: One Year on a Disappearing Island by Peter Rudiak-Gould

My girlfriend is Marshallese. Most people, upon hearing that, say "Huh?" The capitol of the Marshall Islands, Majuro, has only about 20k people. Yet these small Pacific islands played a key role for the Allies in WWII, most famously at bikini island, site of atom bomb testing. But there are very few books written about this collection of atolls. Rudiak-Gould's book chronicles his year teaching at a rural school in Ujae, one of the poorest, most remote atolls in the Marshall Islands.

Rudiak-Gould is an adept writer. One thing I love about this book is his honesty. He does not paint his time as a simple and gloved return to a simple or pure culture. It is tough. The cultural shock is tough, the language barrier is tough, trying to figure out the local etiquette is tough. He recounts some pretty nasty thoughts he had about the people of Ujae.

Yet this nastiness and difficulty was ultimately what transformed Rudiak-Gould. By the end of his time there he felt he had begun to understand a culture where nobody shows emotion and where deadlines and meetings are flexible at best. He peppers his book with fascinating stories about the language, the culture, and the history of the Marshallese that demonstrate that knowledge.

Since writing this book, Rudiak-Gould has gone on to earn a PhD at Oxford, using anthropological methods to study how the Marshallese conceptualize and act on the looming threat of climate change that could sink much of their nation. He has even written a textbook of the Marshallese language, one of two extant in English. As he writes:

"My mission here was self-contradictory. My duty was to help the community, but also to accept it as it is. As an international volunteer, I had been given these two incompatible goals and had never noticed that quandary until now. If I adopted my host community's apathy toward education, I would achieve greater cultural integration but fail at making a positive contribution. If I crusaded for education, I could make a positive contribution but fail at integrating into the culture. There was no way around the dilemma…"

It is these dilemmas and contradictions that he works through during his time at Ujae, never resolving them but finding ways to live in their tensions. As a reader, I enjoyed being along for the ride.

Cross' book, first published in 1959 when the Dead Sea Scrolls were a new discovery, has been rewritten in this 1990s edition. It provides an overview of the manuscript finds and how they impact biblical studies as a whole. Though it is too scholarly for the general reader, too jam packed with footnotes, it has some high points.

A professor told me to read this book as background for the research she is doing with one of the DSS manuscripts, the minor prophets scroll. While I read the chapter on Old Testament textual criticism, the most interesting section for me was that on Essenes and primitive Christianity. Though the Essenes were not Christian, there are a lot of parallels: both are apocalyptic communities, both believe they live in the last age, both see their religious movement as the fulfillment of past prophecy. Like Paul, the Essenes eschewed marriage. (Why bother marrying when the world will end soon?) Both were tightly-knit communities with little or no sense of private property.