edwinbcn's 2013 Books

Ce sujet est poursuivi sur edwinbcn's 2013 Books - Part 2.

DiscussionsClub Read 2013

Rejoignez LibraryThing pour poster.

1edwinbcn

My participation in Club Read 2012 has been very satisfactory. Reading the threads by all other members has inspired me, and this year I will certainly read some books reviewed by some of you guys / gals in 2012.

Club Read 2012 has stimulated my reading. By the end of December, I will have finish reading about 158 books, that is 8 books over my target of 150 for 2012.

Unfortunately, my job has periods of frantic activity, burdening me with the reading of students' papers, which slows me down twice six weeks each year, at the end of the term. Busy work also keeps me from reading along with very demanding reading groups. It remains a pity I don't have the concentration and time to read along with some of your major works selections. Also, because I cannot acquire the publications fast enough, either because they are in storage in my home country or not available in China.

My reading plans for 2013 are:

* more about China (mainly secondary literature)

* more professional literature

* more French and Spanish

Two other resolutions are:

* Buy fewer books (last year was gluttonous)

* Make more use of my Kindle (in use since November)

Club Read 2012 has stimulated my reading. By the end of December, I will have finish reading about 158 books, that is 8 books over my target of 150 for 2012.

Unfortunately, my job has periods of frantic activity, burdening me with the reading of students' papers, which slows me down twice six weeks each year, at the end of the term. Busy work also keeps me from reading along with very demanding reading groups. It remains a pity I don't have the concentration and time to read along with some of your major works selections. Also, because I cannot acquire the publications fast enough, either because they are in storage in my home country or not available in China.

My reading plans for 2013 are:

* more about China (mainly secondary literature)

* more professional literature

* more French and Spanish

Two other resolutions are:

* Buy fewer books (last year was gluttonous)

* Make more use of my Kindle (in use since November)

2mene

You also posted a similar topic here: http://www.librarything.nl/topic/146972# Only with 2013 instead of 2012?

3edwinbcn

They are the same, but I cannot delete the other. Since you've chose this one, this one it's gonna be ;-)

4mene

Maybe change the 2012 in this thread to 2013 then :P ? In the sentence "My reading plans for 2012 are:"

Maybe a moderator can delete the other topic.

Though I should've commented on the other thread then ^^;

Maybe a moderator can delete the other topic.

Though I should've commented on the other thread then ^^;

6absurdeist

I'm w/you on buying fewer books this year, though there still are so many to buy, calling to me ...

Looking forward to following your reading this year.

Looking forward to following your reading this year.

7arubabookwoman

I've enjoyed following your reading last year (without commenting), and look forward to doing so again this year. I am in awe of the number of languages you read in!

9edwinbcn

HAPPY NEW YEAR!

I finally finished up writing the remaining reviews over at Club Read 2012 edwinbcn's Reading Journal 2012, Part 2

For those of you who haven't looked at Club Read 2012 since December 31, I am listing here the last 15 books reviewed since that date.

140. Pawels Briefe. Eine Familiengeschichte

141. Haanvroeg

142. The Prague cemetery

143. Eigentlich möchte Frau Blum den Milchmann kennenlernen, 21 Geschichten

144. You went away

145. Too loud a solitude

146. Erasmus

147. Forbidden colours

148. Wanderungen im Norden

149. Wachsender Mond, 1985 - 1988

150. Im Dunkeln singen, 1982 bis 1985

151. This is water. Some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion, about living a compassionate life

152. Don't fall off the mountain

153. Affinity

154. Korea. A walk through the land of miracles

155. Rheinsberg – ein Bilderbuch für Verliebte

I finally finished up writing the remaining reviews over at Club Read 2012 edwinbcn's Reading Journal 2012, Part 2

For those of you who haven't looked at Club Read 2012 since December 31, I am listing here the last 15 books reviewed since that date.

140. Pawels Briefe. Eine Familiengeschichte

141. Haanvroeg

142. The Prague cemetery

143. Eigentlich möchte Frau Blum den Milchmann kennenlernen, 21 Geschichten

144. You went away

145. Too loud a solitude

146. Erasmus

147. Forbidden colours

148. Wanderungen im Norden

149. Wachsender Mond, 1985 - 1988

150. Im Dunkeln singen, 1982 bis 1985

151. This is water. Some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion, about living a compassionate life

152. Don't fall off the mountain

153. Affinity

154. Korea. A walk through the land of miracles

155. Rheinsberg – ein Bilderbuch für Verliebte

10edwinbcn

001. The Google Book

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

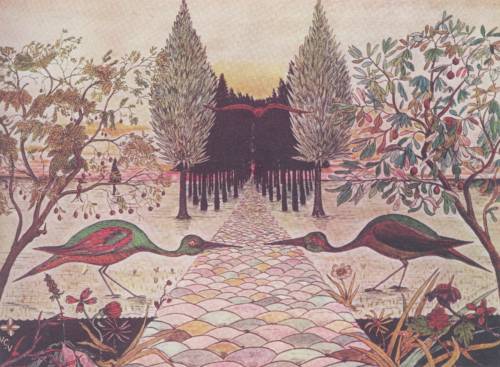

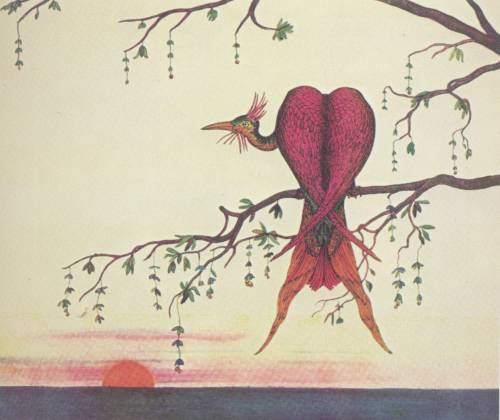

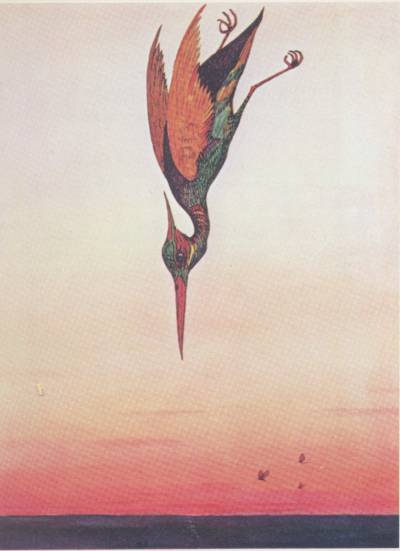

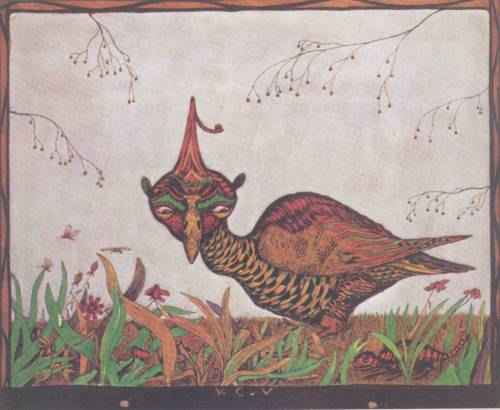

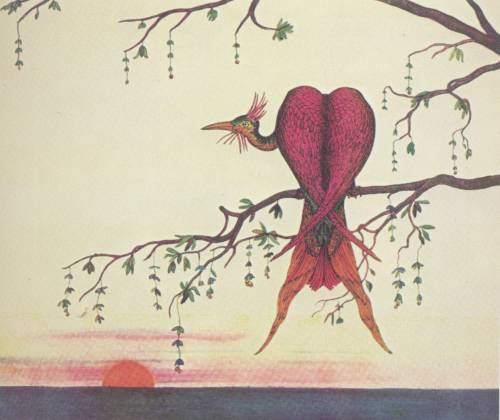

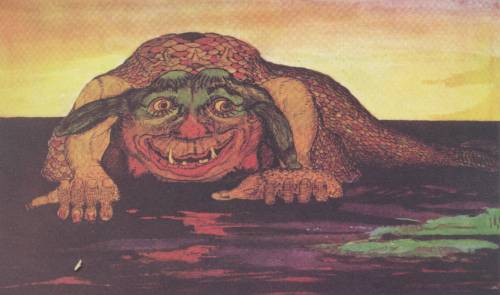

Published in 1913, The Google Book is a picture book with short poems about imaginary birds. The illustrations consist of exquisite water colours. The book must be a joy for children, and their parents alike. Wonderful!

FAR! FAR away, the Google lives, in a land which only children can go to. It is a wonderful land of funny flowers, and birds, and hills of pure white heather.

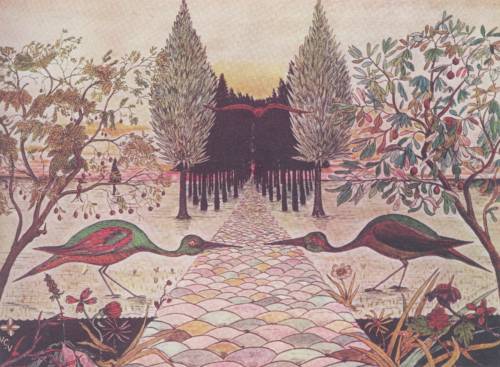

The Google's Garden (Looking West):

You can never see these birds anywhere except in Google land which is far far away, and only children can go there; and even they must be nearly – but not quite – asleep.

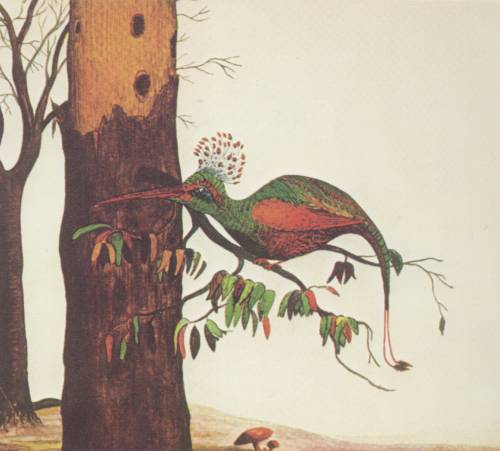

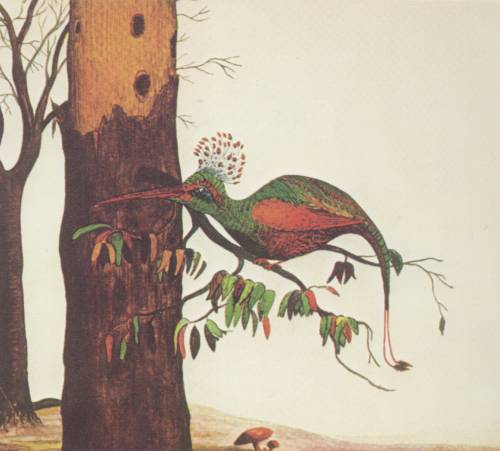

The Lesser Nockit

How can one describe this remarkable bird

Which no one has seen and which everyone's heard;

It hammers and knocks on the trees and the rocks,

And batters and raps at the windy,

And rattles old bones and shuffles the stones

And kicks up a terribly shindy

And hullaballoo!

It never stops still and it makes people ill

With its nerve-racking ear-splitting cry,

Which it utters they say both by night and by day,

And really I cannot think why!

No more can you!

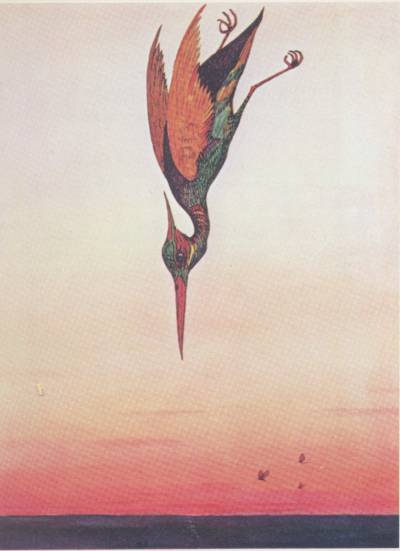

The Junket

The little Junket spots his food

From almost any altitude,

Volplanés from an awful height

And plunges almost out of sight!

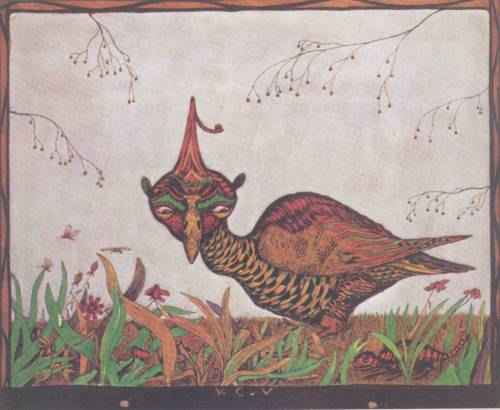

The Swank

The Swank is quick and full of vice,

He tortures beetles also mice.

He bites their legs off and he beats them

Into a pulp, and then he eats them.

The Mirabelle

Old sailors have a tale they tell,

How once the song of a Mirabelle

Enticed a ship upon the rocks

Where perished all the crew.

I think it most improbable

That such a bird would cast a spell

Upon a ship, don't you?

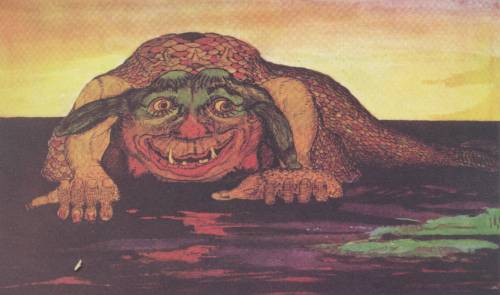

The Google

The Google has a beautiful garden which is guarded night and day. All through the day he sleeps in a pool of water in the center of the garden; but when the night comes, he slowly crawls out of the pool and silently prowls around for food.

The sun is setting –

Can't you hear

A something in the distance

Howl!!?

I wonder if it's –

Yes!! it is

That horrid Google

On the prowl!!!

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

Published in 1913, The Google Book is a picture book with short poems about imaginary birds. The illustrations consist of exquisite water colours. The book must be a joy for children, and their parents alike. Wonderful!

FAR! FAR away, the Google lives, in a land which only children can go to. It is a wonderful land of funny flowers, and birds, and hills of pure white heather.

The Google's Garden (Looking West):

You can never see these birds anywhere except in Google land which is far far away, and only children can go there; and even they must be nearly – but not quite – asleep.

The Lesser Nockit

How can one describe this remarkable bird

Which no one has seen and which everyone's heard;

It hammers and knocks on the trees and the rocks,

And batters and raps at the windy,

And rattles old bones and shuffles the stones

And kicks up a terribly shindy

And hullaballoo!

It never stops still and it makes people ill

With its nerve-racking ear-splitting cry,

Which it utters they say both by night and by day,

And really I cannot think why!

No more can you!

The Junket

The little Junket spots his food

From almost any altitude,

Volplanés from an awful height

And plunges almost out of sight!

The Swank

The Swank is quick and full of vice,

He tortures beetles also mice.

He bites their legs off and he beats them

Into a pulp, and then he eats them.

The Mirabelle

Old sailors have a tale they tell,

How once the song of a Mirabelle

Enticed a ship upon the rocks

Where perished all the crew.

I think it most improbable

That such a bird would cast a spell

Upon a ship, don't you?

The Google

The Google has a beautiful garden which is guarded night and day. All through the day he sleeps in a pool of water in the center of the garden; but when the night comes, he slowly crawls out of the pool and silently prowls around for food.

The sun is setting –

Can't you hear

A something in the distance

Howl!!?

I wonder if it's –

Yes!! it is

That horrid Google

On the prowl!!!

11edwinbcn

002. Fantastic beasts and where to find them

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

Fantastic beasts and where to find them by Artemis Fido "Newt" Scamander is known to be one of Harry Potter's schoolbooks. It consists of a reference guide to the natural history of fantastic beasts.

While most readers will be familiar with such animals as the Centaur, Sphinx, Merpeople, Fairy, Dragon and Unicorn, and may even have observed the Salamander in its natural habitat, the majority of animals in this guide are rarely observed in the wild. The guide describes fantastic beasts worldwide, but seems to concentrate on North-West Europe; it would have been prudent, had the editor indicated this somewhat limited scope.

While many animals are well-known through local folklore, it is to be hoped that international travel guides soon learn from this publication to warn travellers to the dangers they may unknowingly expose themselves when travelling to Africa, or Bornea, for instance, the dwelling place of the Acromantula.

Contrary to The Google Book, Fantastic beasts and where to find them is sparsely illustrated, with occasional BW sketches of some of the less gruesome specimens, with the exception of the red-haired, spider-like Quitaped, a.k.a. "the Hairy MacBoon".

Fantastic beasts and where to find them classifies the fantastic animals into five categories of danger to Wizards and Muggles. It is very useful to know that a number of these animals are carnivorous, having sheep, pigs or human beings as their favourite prey.

A weakness of Fantastic beasts and where to find them is that it is limited to describing fauna, and neglects flora. While this edition comes with a lengthy foreword, and footnotes elucidating particulars with regard to the animals, there are no cross-references or explanations to specimens of plants, fungus or lichens. Thus, while well-read Muggles have no difficulty identifying Mandrake, the favourite diet of the Dugbog, the average reader may be hard-pressed for knowledge of Alihotsy, the leaves of which may cause hysteria upon ingestion, to which the Glumbumble produces an antidote in the form of a melancholy-inducing treacle.

Undoubtedly, in as much as magic potions contain parts of animals, and animals' excretions, fresh and dried plant parts must surely belong to their ingredients, and one wonders whether a companion volume with special interest in fantastic flora would hit the shelves. A preliminary survey shows that such a volume could include species such as Alraune, Audrey var., Broxlorthian Squidflower, Bubotuber, Cow plant (Laganaphyllis simnovorii), Flitterbloom, Katterpod, Leaping toadstool, Papadalupapadipu, Peya, Sapient Pearwood, Sukebind, Triffids, Tumtum tree, and the Walking tree of Dahomey (Quercus nicholas parsonus), to name just a few. Otherwise, it is to be hoped that there will soon be trade editions of works such as

One Thousand Magical Herbs and Fungi by Phyllida Spore, the Encyclopædia of Toadstools, Magical Mediterranean Water Plants and their Properties and Flesh-eating Trees of the World.

Unfortunately, Fantastic beasts and where to find them is not complete and contains at least one error. To begin with the latter, the paperback edition incorrectly lists the Erkling on page 27, which should obviously be the Erlking. Ashamedly, even a bright student such as Harry Potter, has not seen or noticed this error. It is to be hoped that this error will be corrected in the next edition. Furthermore, a large number of fantastic beasts are omitted, such as the Blast-Ended Skrewt, the Fire Slug, the Hinkypunk a.k.a. Will-o'-the-wisp, the Nargle and the Vampyr Mosp. It would be nice if future editions would include cross references to the Snidget and the Golden Snidget, while the editor could be clearer on the sub-species of Merpeople, viz. Mermaid, Merrow and Selkie, and likewise indicate the status of the Puffskein versus the Pygmy Puff.

Finally, one would expect some comment, or an appendix with some explanations for animals of lesser known status, such as Banshees, Boggarts, House-elves, Cockatrices, Dwarfs, Dementors, Fluffy, Giants, Mummies and Veela and the status and classification of creatures such as the Bicorns, Blibbering Humdinger, Blood-Sucking Bugbears, Crumple-Horned Snorkack, Gulping Plimpy, Heliopath and Wrackspurt. On the other hand, it could be argued that inclusion of these latter specimens would fall beyond the scope of a schoolbook, and be more appropriate to a more specialized guide, such as The Monster Book of Monsters.

A very interesting and edifying read, indeed.

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

Fantastic beasts and where to find them by Artemis Fido "Newt" Scamander is known to be one of Harry Potter's schoolbooks. It consists of a reference guide to the natural history of fantastic beasts.

While most readers will be familiar with such animals as the Centaur, Sphinx, Merpeople, Fairy, Dragon and Unicorn, and may even have observed the Salamander in its natural habitat, the majority of animals in this guide are rarely observed in the wild. The guide describes fantastic beasts worldwide, but seems to concentrate on North-West Europe; it would have been prudent, had the editor indicated this somewhat limited scope.

While many animals are well-known through local folklore, it is to be hoped that international travel guides soon learn from this publication to warn travellers to the dangers they may unknowingly expose themselves when travelling to Africa, or Bornea, for instance, the dwelling place of the Acromantula.

Contrary to The Google Book, Fantastic beasts and where to find them is sparsely illustrated, with occasional BW sketches of some of the less gruesome specimens, with the exception of the red-haired, spider-like Quitaped, a.k.a. "the Hairy MacBoon".

Fantastic beasts and where to find them classifies the fantastic animals into five categories of danger to Wizards and Muggles. It is very useful to know that a number of these animals are carnivorous, having sheep, pigs or human beings as their favourite prey.

A weakness of Fantastic beasts and where to find them is that it is limited to describing fauna, and neglects flora. While this edition comes with a lengthy foreword, and footnotes elucidating particulars with regard to the animals, there are no cross-references or explanations to specimens of plants, fungus or lichens. Thus, while well-read Muggles have no difficulty identifying Mandrake, the favourite diet of the Dugbog, the average reader may be hard-pressed for knowledge of Alihotsy, the leaves of which may cause hysteria upon ingestion, to which the Glumbumble produces an antidote in the form of a melancholy-inducing treacle.

Undoubtedly, in as much as magic potions contain parts of animals, and animals' excretions, fresh and dried plant parts must surely belong to their ingredients, and one wonders whether a companion volume with special interest in fantastic flora would hit the shelves. A preliminary survey shows that such a volume could include species such as Alraune, Audrey var., Broxlorthian Squidflower, Bubotuber, Cow plant (Laganaphyllis simnovorii), Flitterbloom, Katterpod, Leaping toadstool, Papadalupapadipu, Peya, Sapient Pearwood, Sukebind, Triffids, Tumtum tree, and the Walking tree of Dahomey (Quercus nicholas parsonus), to name just a few. Otherwise, it is to be hoped that there will soon be trade editions of works such as

One Thousand Magical Herbs and Fungi by Phyllida Spore, the Encyclopædia of Toadstools, Magical Mediterranean Water Plants and their Properties and Flesh-eating Trees of the World.

Unfortunately, Fantastic beasts and where to find them is not complete and contains at least one error. To begin with the latter, the paperback edition incorrectly lists the Erkling on page 27, which should obviously be the Erlking. Ashamedly, even a bright student such as Harry Potter, has not seen or noticed this error. It is to be hoped that this error will be corrected in the next edition. Furthermore, a large number of fantastic beasts are omitted, such as the Blast-Ended Skrewt, the Fire Slug, the Hinkypunk a.k.a. Will-o'-the-wisp, the Nargle and the Vampyr Mosp. It would be nice if future editions would include cross references to the Snidget and the Golden Snidget, while the editor could be clearer on the sub-species of Merpeople, viz. Mermaid, Merrow and Selkie, and likewise indicate the status of the Puffskein versus the Pygmy Puff.

Finally, one would expect some comment, or an appendix with some explanations for animals of lesser known status, such as Banshees, Boggarts, House-elves, Cockatrices, Dwarfs, Dementors, Fluffy, Giants, Mummies and Veela and the status and classification of creatures such as the Bicorns, Blibbering Humdinger, Blood-Sucking Bugbears, Crumple-Horned Snorkack, Gulping Plimpy, Heliopath and Wrackspurt. On the other hand, it could be argued that inclusion of these latter specimens would fall beyond the scope of a schoolbook, and be more appropriate to a more specialized guide, such as The Monster Book of Monsters.

A very interesting and edifying read, indeed.

12Linda92007

The Google Book looks absolutely delightful, Edwin.

13rebeccanyc

I agree with Linda!

14Cait86

>11 edwinbcn: – Well, the Blast-Ended Skrewt is an illegal cross-breed, so it might be some time before it is included in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Hopefully they never make it out of the Hogwarts' grounds ;)

15edwinbcn

003. Fiere

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

The Scottish poet Jackie Kay writes beautiful poetry. Her poetry is modern, but written in a quiet and pleasant style, with various forms of rhyme; many of her poems have a natural rhythm, and repetition gives some the characteristics of a ballad. Kay's poetry is recognizable and accessible to a large audience.

The poems in Fiere, published in 2011, is her sixth volume of published poetry. The poems in this collection are inspired by friendship in all variety of relations. There are also some poems written alongside Kay's memoir Red dust road, which describes her search for her father in Africa.

The title of the collection, Fiere derives from archaic English or Scottish Gaelic:

Fere, feare, feer, fiere or pheere (archaic)

noun: a companion, a mate, a spouse, an equal

Fere (Scot.)

adj: able, sound

Some of the poems are in Scottish Gaelic, such as the first, with the title Fiere which was commissioned by the Scottish Poetry Library, and which was composed in response to a poem by Robert Burns.

One of the two epigraphs to the collection is from Burns:

And there's a hand, my trusty fiere

And gie's a hand o' thine

Robert Burns

the other epigraph reads:

Wherever someone stands,

something else will stand beside it.

Chinua Achebe

Fiere

If ye went tae the tapmost hill, Fiere

Whaur we used tae clamb as girls,

Ye’d see the snow the day, Fiere,

Settling on the hills.

You’d mind o’ anither day, mibbe,

We ran doon the hill in the snow,

Sliding and singing oor way tae the foot,

Lassies laughing thegither – how braw.

The years slipping awa; oot in the weather.

And noo we’re suddenly auld, Fiere,

Oor friendship’s ne’er been weary.

We’ve aye seen the wurld differently.

Whaur would I hae been weyoot my jo,

My fiere, my fiercy, my dearie O?

Oor hair micht be silver noo,

Oor walk a wee bit doddery,

But we’ve had a whirl and a blast, girl,

Thru’ the cauld blast winter, thru spring, summer.

O’er a lifetime, my fiere, my bonnie lassie,

I’d defend you – you, me; blithe and blatter,

Here we gang doon the hill, nae matter,

Past the bracken, bothy, bonny braes, barley.

Oot by the roaring Sea, still havin a blether.

We who loved sincerely; we who loved sae fiercely.

The snow ne’er looked sae barrie,

Nor the winter trees sae pretty.

C’mon, c’mon my dearie – tak my hand, my fiere!

Perhaps the following poem is perhaps the world’s first (published) epithalamion on the occasion of a gay marriage.

The Marriage of Nick and Edward

When you get home from your wedding, dear boys,

And you’ve exchanged your plain and beautiful bands

—rose-gold with platinum for Nick,

rose-gold with gold for Edward—

and held together your handsome hands,

and kissed, and pledged a life of happiness,

I suggest you get out the Quaich,

your special two-handled drinking bowl—

made of pewter; for your gifted future—

and pour some Hallelujah into the loving cup

and knock back the rose-gold liquid

and drink up, drink up, drink up!

Here are your years stretching ahead,

and the rose-gold love of the newly wed.

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

The Scottish poet Jackie Kay writes beautiful poetry. Her poetry is modern, but written in a quiet and pleasant style, with various forms of rhyme; many of her poems have a natural rhythm, and repetition gives some the characteristics of a ballad. Kay's poetry is recognizable and accessible to a large audience.

The poems in Fiere, published in 2011, is her sixth volume of published poetry. The poems in this collection are inspired by friendship in all variety of relations. There are also some poems written alongside Kay's memoir Red dust road, which describes her search for her father in Africa.

The title of the collection, Fiere derives from archaic English or Scottish Gaelic:

Fere, feare, feer, fiere or pheere (archaic)

noun: a companion, a mate, a spouse, an equal

Fere (Scot.)

adj: able, sound

Some of the poems are in Scottish Gaelic, such as the first, with the title Fiere which was commissioned by the Scottish Poetry Library, and which was composed in response to a poem by Robert Burns.

One of the two epigraphs to the collection is from Burns:

And there's a hand, my trusty fiere

And gie's a hand o' thine

Robert Burns

the other epigraph reads:

Wherever someone stands,

something else will stand beside it.

Chinua Achebe

Fiere

If ye went tae the tapmost hill, Fiere

Whaur we used tae clamb as girls,

Ye’d see the snow the day, Fiere,

Settling on the hills.

You’d mind o’ anither day, mibbe,

We ran doon the hill in the snow,

Sliding and singing oor way tae the foot,

Lassies laughing thegither – how braw.

The years slipping awa; oot in the weather.

And noo we’re suddenly auld, Fiere,

Oor friendship’s ne’er been weary.

We’ve aye seen the wurld differently.

Whaur would I hae been weyoot my jo,

My fiere, my fiercy, my dearie O?

Oor hair micht be silver noo,

Oor walk a wee bit doddery,

But we’ve had a whirl and a blast, girl,

Thru’ the cauld blast winter, thru spring, summer.

O’er a lifetime, my fiere, my bonnie lassie,

I’d defend you – you, me; blithe and blatter,

Here we gang doon the hill, nae matter,

Past the bracken, bothy, bonny braes, barley.

Oot by the roaring Sea, still havin a blether.

We who loved sincerely; we who loved sae fiercely.

The snow ne’er looked sae barrie,

Nor the winter trees sae pretty.

C’mon, c’mon my dearie – tak my hand, my fiere!

Perhaps the following poem is perhaps the world’s first (published) epithalamion on the occasion of a gay marriage.

The Marriage of Nick and Edward

When you get home from your wedding, dear boys,

And you’ve exchanged your plain and beautiful bands

—rose-gold with platinum for Nick,

rose-gold with gold for Edward—

and held together your handsome hands,

and kissed, and pledged a life of happiness,

I suggest you get out the Quaich,

your special two-handled drinking bowl—

made of pewter; for your gifted future—

and pour some Hallelujah into the loving cup

and knock back the rose-gold liquid

and drink up, drink up, drink up!

Here are your years stretching ahead,

and the rose-gold love of the newly wed.

16SassyLassy

Oh dear. Edwin, I knew you'd be dangerous this year and already I have two more books to look for: The Google Book and Fiere. Wonderful excerpts from both.

17janeajones

Ooh -- how nice to start out the year with such delightful poetry (and gorgeous pictures)!

18baswood

Fantastic start to your new thread Edwin.

There is really only one tome that you need for fantastic monsters and that is: D & D Monster Manual

There is really only one tome that you need for fantastic monsters and that is: D & D Monster Manual

19edwinbcn

> 18

Thanks, Barry. Cyberspace in another domain altogether.

To carry the discussion over from the 2012 thread, yes, I thought you might be interested in the Erasmus biography by Huizinga.

The book was really full of wonderful details. For example, we learn that in Erasmus' time it was customary for travellers to sleep two-to-a-bed. At the opening of Moby Dick Ishmael has to share a bed with Queequeg. We get the feeling that this is normal in that setting, but only because the inn is so full. Nowadays, we wouldn't want to share a room with a stranger, in most cases.

Thanks, Barry. Cyberspace in another domain altogether.

To carry the discussion over from the 2012 thread, yes, I thought you might be interested in the Erasmus biography by Huizinga.

The book was really full of wonderful details. For example, we learn that in Erasmus' time it was customary for travellers to sleep two-to-a-bed. At the opening of Moby Dick Ishmael has to share a bed with Queequeg. We get the feeling that this is normal in that setting, but only because the inn is so full. Nowadays, we wouldn't want to share a room with a stranger, in most cases.

20dchaikin

The sleeping two-per bed came up in a Lincoln biography too. When he occasionally wrote or said he slept with so and so, he actually meant they what he said, sans the euphemism.

Good stuff here. Your review of Fantastic Beasts was great fun to read.

Good stuff here. Your review of Fantastic Beasts was great fun to read.

22detailmuse

>15 edwinbcn: accessible to a large audience

Some of the poems are in Scottish Gaelic

Seemed conflicting but then I read "Fiere" and loved it. Loved both, and the topic of friendship.

Some of the poems are in Scottish Gaelic

Seemed conflicting but then I read "Fiere" and loved it. Loved both, and the topic of friendship.

23edwinbcn

004. All over

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

All over is a collection of 19 short stories, by the American author Roy Kesey. Kesey is the author of four books, Nanjing: A Cultural and Historical Guide, and two short stories collections: Nothing in the World, and All over, written and published in 2007 while living in Beijing, and his latest, Pacazo, a novel published in 2011. Kesey now resides in Maryland

At a total of 145 pages, this means each story in All over is very short, at an average length of just about eight pages. All stories are highly charged with a feverish energy and dynamic, and some of them are characterised by a frantic verbosity, which make them somewhat difficult to read, and require attentive reading. The writing can be called experimental, with parts of regular prose interspersed with ultra-short paragraphs, and short-style dialogue, which raises the pace of reading. Formal and informal styles are mixed.

The premise of most stories is some form of weirdness, but very close to real-life experience. For instance, the first story, "Invunche y voladora" swirls around the irritations that develop between lovers in long relationships, but this couple is newly-wed. Thus, the story bears out the tale of many failed marriages on the first day of honeymoon. Cleverly done, and one of the better stories in the collection.

In the short story "Loess", the narrator is the former Chinese Prime-Minister Zhou Enlai who outlines to Chairman Mao Zedong how they will shape Chinese history. The story is told from their pre-natal perspective.

There are other stories that betray their origin as being written in China, for example, "At the Pizza Hut, the Girls Build Their Towers". The story describes how customers at the Pizza Hut, being restricted to a single serving from the salad bar (used to) pile their salad incredibly high, to maximize the amount of salad ingredients which could be held on top of one (small) salad bowl.

Another story that seems inspired by China is "Scroll", the second story in the collection. It tells the story of an artist who spent 34 years to create a painting that is nine miles long and then fails to find a gallery to show it.

This collection of stories will be very interesting to readers seeking out the avant-garde of modern short-story writing, and it will be interesting to follow the further development of Roy Kesey as an emerging author.

Finished reading: 3 January 2013

All over is a collection of 19 short stories, by the American author Roy Kesey. Kesey is the author of four books, Nanjing: A Cultural and Historical Guide, and two short stories collections: Nothing in the World, and All over, written and published in 2007 while living in Beijing, and his latest, Pacazo, a novel published in 2011. Kesey now resides in Maryland

At a total of 145 pages, this means each story in All over is very short, at an average length of just about eight pages. All stories are highly charged with a feverish energy and dynamic, and some of them are characterised by a frantic verbosity, which make them somewhat difficult to read, and require attentive reading. The writing can be called experimental, with parts of regular prose interspersed with ultra-short paragraphs, and short-style dialogue, which raises the pace of reading. Formal and informal styles are mixed.

The premise of most stories is some form of weirdness, but very close to real-life experience. For instance, the first story, "Invunche y voladora" swirls around the irritations that develop between lovers in long relationships, but this couple is newly-wed. Thus, the story bears out the tale of many failed marriages on the first day of honeymoon. Cleverly done, and one of the better stories in the collection.

In the short story "Loess", the narrator is the former Chinese Prime-Minister Zhou Enlai who outlines to Chairman Mao Zedong how they will shape Chinese history. The story is told from their pre-natal perspective.

There are other stories that betray their origin as being written in China, for example, "At the Pizza Hut, the Girls Build Their Towers". The story describes how customers at the Pizza Hut, being restricted to a single serving from the salad bar (used to) pile their salad incredibly high, to maximize the amount of salad ingredients which could be held on top of one (small) salad bowl.

Another story that seems inspired by China is "Scroll", the second story in the collection. It tells the story of an artist who spent 34 years to create a painting that is nine miles long and then fails to find a gallery to show it.

This collection of stories will be very interesting to readers seeking out the avant-garde of modern short-story writing, and it will be interesting to follow the further development of Roy Kesey as an emerging author.

26zenomax

The story describes how customers at the Pizza Hut, being restricted to a single serving from the salad bar (used to) pile their salad incredibly high, to maximize the amount of salad ingredients which could be held on top of one (small) salad bowl.

My wife invariably conducts herself in this fashion where there is a salad bar (curiously, even where there is no 'single serving' rule).

My wife invariably conducts herself in this fashion where there is a salad bar (curiously, even where there is no 'single serving' rule).

27RidgewayGirl

Well, I've added it to my list of books to keep an eye out for.

28edwinbcn

005. Landesbühne

Finished reading: 4 January 2013

Landesbühne ("Countryside Theatre") is a short novel by the German author Siegfried Lenz. Like Schweigeminute, (transl. A Minute's Silence) reviewed here, Landesbühne feels closer to Anglo-American literature, than to German literature.

In fact, the story is so accessible that it feels as if you've read it somewhere else. Perhaps, this effect is created by the hyper-realistic setting. At the centre of the story are two prisoners, one, a professor, Clemens, who seduced students in exchange for fraudulent exam results, and his cellmate, Hannes. The prison is located near a small town. The mayor of the town promotes a project, aimed at raising the town's profile. To this effect, the prisoners are brought to the town by bus to participate in the cultural activities which are part of the annual Carnation Festival. Throughout the week, the prisoners sleep in the bus, rather than being brought back to the prison. Typically, this inspires some inmates to escape. Clemens, who has completed half of his four-year imprisonment period decides not to flee. Back in his cell, he finds that Hannes has decided to stay as well. Respect and friendship are the main motives.

Landesbühne is a very short, and easy read. A bit too easy, perhaps.

Other books I have read by Siegfried Lenz:

Schweigeminute

Ein Kriegsende

Finished reading: 4 January 2013

Landesbühne ("Countryside Theatre") is a short novel by the German author Siegfried Lenz. Like Schweigeminute, (transl. A Minute's Silence) reviewed here, Landesbühne feels closer to Anglo-American literature, than to German literature.

In fact, the story is so accessible that it feels as if you've read it somewhere else. Perhaps, this effect is created by the hyper-realistic setting. At the centre of the story are two prisoners, one, a professor, Clemens, who seduced students in exchange for fraudulent exam results, and his cellmate, Hannes. The prison is located near a small town. The mayor of the town promotes a project, aimed at raising the town's profile. To this effect, the prisoners are brought to the town by bus to participate in the cultural activities which are part of the annual Carnation Festival. Throughout the week, the prisoners sleep in the bus, rather than being brought back to the prison. Typically, this inspires some inmates to escape. Clemens, who has completed half of his four-year imprisonment period decides not to flee. Back in his cell, he finds that Hannes has decided to stay as well. Respect and friendship are the main motives.

Landesbühne is a very short, and easy read. A bit too easy, perhaps.

Other books I have read by Siegfried Lenz:

Schweigeminute

Ein Kriegsende

30edwinbcn

>24 baswood:, 29

My original rating, after I finished reading All over was 1.5 stars. However, I sometimes adjust this rating after writing the review, as reviewing makes you look at a book somewhat differently, and writing it all up seems to bear the real value out.

In this case, I was a bit over-enthusiastic, and upgraded the rating to four stars. However, as Barry remarked, four out of five for this books quite mars with my regular rating, so I readjusted the rating back to 1.5.

1.5 means it is readable, but could not really captivate me, and I had difficulty concentrating. The style and structure are experimental, and therefore not really comfortable to read. The depth of human experience in somewhat shallow.

At the same time, bearing in mind that this is a new author, the work is interesting, and I will definitely read more by this author.

I suppose there will be other readers who can appreciate the stories much more than I do.

My original rating, after I finished reading All over was 1.5 stars. However, I sometimes adjust this rating after writing the review, as reviewing makes you look at a book somewhat differently, and writing it all up seems to bear the real value out.

In this case, I was a bit over-enthusiastic, and upgraded the rating to four stars. However, as Barry remarked, four out of five for this books quite mars with my regular rating, so I readjusted the rating back to 1.5.

1.5 means it is readable, but could not really captivate me, and I had difficulty concentrating. The style and structure are experimental, and therefore not really comfortable to read. The depth of human experience in somewhat shallow.

At the same time, bearing in mind that this is a new author, the work is interesting, and I will definitely read more by this author.

I suppose there will be other readers who can appreciate the stories much more than I do.

31edwinbcn

006. The forgotten waltz

Finished reading: 6 January 2013

Readers' appreciation of a novel often depend on the extent to which they can identify with the main character. In The forgotten waltz, the main character, Gina Moynihan is a selfish and egotistical woman, and therefore, readers tend to dislike the character as well as the novel.

It is brave of Anne Enright to write a novel in which the narrator is a dislikable character. As a type, this protagonist is probably universal: a self-conscious, ambitious and modern woman, who is driven by unscrupulous lust and ambition. She is not 100% bad or evil. She is just that type of person, perhaps quite typical of the 1990s and early decades of the 21 century, that type of go-getter, with a good job, an eye always on stock market and real estate prices, believing social darwinism means cruelty is part of social competitiveness. Naturally, this is not the way she perceives herself. In her own self-perception, Gina appears a quite normal, emancipated woman. There are some (not so) subtle hints in the first part of the books that Gina would think of herself as particularly pure, worried of smut and dirt. There are several times references suggesting that other people are abnormal or weak, in her eyes. Gina's character is soon enough clear to the reader, who will realize that Gina should be considered an unreliable narrator. Her analysis of social relations, or morals and of her own motivations is incorrect.

While omitting any specific reasons, Gina seduces Seán Vallely at a barbecue party in her sister's garden. The total randomess of their relationship is emphasised by Gina's characterization of how it came about. She was looking intently at a man who was turned away from her. Had he not turned around, she would have let him go, but as he did turn around and face her, she made her move.

From the way Gina has described her husband Conor, mentally undressing him as in her mind she strips his well-built body -- a jacket, and under that a shirt, and under that a T-shirt, and under that a tattoo...-- it is clear that Gina picks her man on physical appearance and her own lust rather than anything else. The fact that Seán is married matters not to her. The time when adultery was a man's thing lies far in the past.

Apparently, Gina is very successful at seducing Seán, but meets one obstacle: the couple's daughter, Evie. The child is a factor that Gina has not reckoned with, and completely underestimates.

Ever since Freud, it is clear that children are no longer just innocent. The novella that first attested to that insight is probably Henry James' What Masie knew. The forgotten waltz is a modern variation on this theme.

Anne Enright's prose is almost as understated as that of Beryl Bainbridge, but gives the reader more clues. Likewise, The forgotten waltz is a fairly thin novel.

True, The forgotten waltz was not quite an enjoyable read, but then leaves the reader with a lot to ponder.

Finished reading: 6 January 2013

Readers' appreciation of a novel often depend on the extent to which they can identify with the main character. In The forgotten waltz, the main character, Gina Moynihan is a selfish and egotistical woman, and therefore, readers tend to dislike the character as well as the novel.

It is brave of Anne Enright to write a novel in which the narrator is a dislikable character. As a type, this protagonist is probably universal: a self-conscious, ambitious and modern woman, who is driven by unscrupulous lust and ambition. She is not 100% bad or evil. She is just that type of person, perhaps quite typical of the 1990s and early decades of the 21 century, that type of go-getter, with a good job, an eye always on stock market and real estate prices, believing social darwinism means cruelty is part of social competitiveness. Naturally, this is not the way she perceives herself. In her own self-perception, Gina appears a quite normal, emancipated woman. There are some (not so) subtle hints in the first part of the books that Gina would think of herself as particularly pure, worried of smut and dirt. There are several times references suggesting that other people are abnormal or weak, in her eyes. Gina's character is soon enough clear to the reader, who will realize that Gina should be considered an unreliable narrator. Her analysis of social relations, or morals and of her own motivations is incorrect.

While omitting any specific reasons, Gina seduces Seán Vallely at a barbecue party in her sister's garden. The total randomess of their relationship is emphasised by Gina's characterization of how it came about. She was looking intently at a man who was turned away from her. Had he not turned around, she would have let him go, but as he did turn around and face her, she made her move.

From the way Gina has described her husband Conor, mentally undressing him as in her mind she strips his well-built body -- a jacket, and under that a shirt, and under that a T-shirt, and under that a tattoo...-- it is clear that Gina picks her man on physical appearance and her own lust rather than anything else. The fact that Seán is married matters not to her. The time when adultery was a man's thing lies far in the past.

Apparently, Gina is very successful at seducing Seán, but meets one obstacle: the couple's daughter, Evie. The child is a factor that Gina has not reckoned with, and completely underestimates.

Ever since Freud, it is clear that children are no longer just innocent. The novella that first attested to that insight is probably Henry James' What Masie knew. The forgotten waltz is a modern variation on this theme.

Anne Enright's prose is almost as understated as that of Beryl Bainbridge, but gives the reader more clues. Likewise, The forgotten waltz is a fairly thin novel.

True, The forgotten waltz was not quite an enjoyable read, but then leaves the reader with a lot to ponder.

32Linda92007

Excellent review of The Forgotten Waltz, Edwin. I saw Enright give a talk on this book and it did not compel me to read it. But I did like The Gathering, which many did not.

33dmsteyn

Good review, Edwin. The book does seem to elicit a knee-jerk response because of its protagonist, which is unfortunate. I have The Gathering, so I'll try that before deciding about this one.

34edwinbcn

007. Die Kirschen der Freiheit

Finished reading: 9 January 2013

Published in English as:

Published in English as:

Quite a number of German authors who started their career at the time of the Nazi German Third Reich, and became celebrated authors of the postwar period, are now forgotten or in disrepute. Especially those writers who did not go into exile are under fire as their integrity is questioned. For many authors whose career was built during the late 1940s to circa mid 1980s no substantial evidence existed except for personal testimonies by eye witnesses or close relations with whom they may have shared the most intimate details of their personal histories. These personal testimonies are only recently appearing or made known to the public. In some cases, as with Alfred Andersch speculation has proved to be without foundation. Still, any dispute of an author's moral integrity must negatively influence readers' ideas, even though the value of the authors' works are not reevaluated.

Die Kirschen der Freiheit is a beautifully written personal account of pre-war Germany and the Nazi period from about 1919 to 1945. It should definitely be considered on a par with for instance Ernst Toller's Eine Jugend in Deutschland.

Andersch biography Die Kirschen der Freiheit starts with the demise of the Munich Soviet Republic (Münchner Räterepublik) in 1919. In subsequent years, with a father who is a fanatic Hitler fan, Alfred became a leader the a Communist youth organization, for which he was arrested and locked up in the concentration camp Dachau in 1933. This instills so much fear in the young Alfred Andersch that after his release he abandons his political activities and turns to the relatively innocent occupation or art and writing. He describes how circumstances force him to cheer and welcome Hitler as the new Reichskanzler a few months later, waving a little flag as Hitler's motorcade passes through the streets.

Next, the autobiography describes how Andersch, who was conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht) since 1940, deserted from his unit while fighting on the last front in Italy in June 1944. While his desertion seems frightfully simple, the reader is persuaded to feel the fear of doing so, as recapture would inevitably have meant immediate execution.

Apart from a (personal) history, Die Kirschen der Freiheit explores the question to what extent personal human freedom can be said to exist. Obviously, none of Andersch actions and life since his arrest in 1933 were motivated by even the merest semblance of free will, but more likely the result of a lifelong fear. In addition, Andersch explores the question to what extent an oath is binding in creating loyalty to a loathed master. Andersch conclusion is that people are never really free, and that freedom only exists in rare moments, which may possibly even only occur once in a lifetime. For who is ever truly free from fear or duty?

Other books I have read by Alfred Andersch:

Wanderungen im Norden

"... einmal wirklich leben". Ein Tagebuch in Briefen an Hedwig Andersch, 1943 bis 1975

Finished reading: 9 January 2013

Published in English as:

Published in English as:

Quite a number of German authors who started their career at the time of the Nazi German Third Reich, and became celebrated authors of the postwar period, are now forgotten or in disrepute. Especially those writers who did not go into exile are under fire as their integrity is questioned. For many authors whose career was built during the late 1940s to circa mid 1980s no substantial evidence existed except for personal testimonies by eye witnesses or close relations with whom they may have shared the most intimate details of their personal histories. These personal testimonies are only recently appearing or made known to the public. In some cases, as with Alfred Andersch speculation has proved to be without foundation. Still, any dispute of an author's moral integrity must negatively influence readers' ideas, even though the value of the authors' works are not reevaluated.

Die Kirschen der Freiheit is a beautifully written personal account of pre-war Germany and the Nazi period from about 1919 to 1945. It should definitely be considered on a par with for instance Ernst Toller's Eine Jugend in Deutschland.

Andersch biography Die Kirschen der Freiheit starts with the demise of the Munich Soviet Republic (Münchner Räterepublik) in 1919. In subsequent years, with a father who is a fanatic Hitler fan, Alfred became a leader the a Communist youth organization, for which he was arrested and locked up in the concentration camp Dachau in 1933. This instills so much fear in the young Alfred Andersch that after his release he abandons his political activities and turns to the relatively innocent occupation or art and writing. He describes how circumstances force him to cheer and welcome Hitler as the new Reichskanzler a few months later, waving a little flag as Hitler's motorcade passes through the streets.

Next, the autobiography describes how Andersch, who was conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht) since 1940, deserted from his unit while fighting on the last front in Italy in June 1944. While his desertion seems frightfully simple, the reader is persuaded to feel the fear of doing so, as recapture would inevitably have meant immediate execution.

Apart from a (personal) history, Die Kirschen der Freiheit explores the question to what extent personal human freedom can be said to exist. Obviously, none of Andersch actions and life since his arrest in 1933 were motivated by even the merest semblance of free will, but more likely the result of a lifelong fear. In addition, Andersch explores the question to what extent an oath is binding in creating loyalty to a loathed master. Andersch conclusion is that people are never really free, and that freedom only exists in rare moments, which may possibly even only occur once in a lifetime. For who is ever truly free from fear or duty?

Other books I have read by Alfred Andersch:

Wanderungen im Norden

"... einmal wirklich leben". Ein Tagebuch in Briefen an Hedwig Andersch, 1943 bis 1975

35dmsteyn

The Cherries of Freedom, right? (My German isn't great, but I still remember a few basics, and some words are quite close to Afrikaans). Sounds incredibly interesting, Edwin. Your high rating is also enticing.

36edwinbcn

> Yes, Dewald. Thanks for pointing that out. I usually check whether an English translation is available, but with only 47 copies on LT I had assumed that it had not been translated.

37dmsteyn

>36 edwinbcn: I actually didn't even check whether there was a translation, just translated it for myself ;)

Now I wonder whether to try reading it in German, or to stick with the English...

Now I wonder whether to try reading it in German, or to stick with the English...

38RidgewayGirl

That does sound interesting. And to elicit five stars, as well! I'll keep an eye out for it.

I really enjoyed The Forgotten Waltz, but I can see how the personality and actions of the protagonist could be off-putting, I think I liked it in part because of her. I liked diving into the thoughts and motivations of someone so different from myself.

I really enjoyed The Forgotten Waltz, but I can see how the personality and actions of the protagonist could be off-putting, I think I liked it in part because of her. I liked diving into the thoughts and motivations of someone so different from myself.

39edwinbcn

>38 RidgewayGirl: You might, Alison, especially with your upcoming relocation to Munich, which was politically very much astir during the first half of the Twentieth century. You might also want to have a look at the German expressionist author Ernst Toller.

I did not really dislike reading The Forgotten Waltz, although much of my appreciation developed contemplating the novel after I finished reading it. The low rating is not based on the unsympathetic character of Gina, but more on the understated, sparse prose style. The plot is not very interesting, except if you are very interested in the psychology of the main character.

I did not really dislike reading The Forgotten Waltz, although much of my appreciation developed contemplating the novel after I finished reading it. The low rating is not based on the unsympathetic character of Gina, but more on the understated, sparse prose style. The plot is not very interesting, except if you are very interested in the psychology of the main character.

40RidgewayGirl

I've noted the authors. Thank you.

41edwinbcn

008. Arabesques. A tale of double lives

Finished reading: 9 January 2013

Boys as dark as violets

Arabesques. A tale of double lives is Robert Dessaix' very personal, and very subjective biography of André Gide. In fact, it is more of a kaleidoscopic travelogue than a biography. The subtitle A tale of double lives refers as much to the double lives led by Gide, as well as the intertwined exploration of the parallels and contrasts between the lives of Gide and the author. In the absence of a clear chronologie, the book has a dream-like quality of preponderences on the life of André Gide and its author Robert Dessaix, as Dessaix retraces Gide's steps in his travels all over the Western Mediterranean, with particular attention to North Africa, as chapter titles suggest visits to Algiers, Blidah, Tornac, Anduze, Morocco, Cuverville (France), Sousse and Biskra.

Without overmuch emphasis, Dessaix clearly emerges from the narrative as a very seasoned, and openly gay person, whose promiscuity may have been tempered with age. On the other hand, Dessaix portrays Gide as a very timid and closeted homosxual, who may not even have considered himself gay, and whose adoration of boys and young men verged on Platonic aestheticism. However, it is clear that Dessaix rejects that image. At the same time, the author seems to be at a loss to explain the apparent lifelong devotion of Gide for his cousin Madeleine, whom he married at a very young age, and is said to have truly and deeply loved. This contrast, the suggestion that Gide came to homosexuality after meeting Oscar Wilde and subsequently lived as a completely repressed homosexual, who may have truly loved his wife, seems to be a construct in the mind of Dessaix which is not really born out by autobiographical facts.

An interesting aspect of Arabesques. A tale of double lives is that it uncovers the history of various Algerian cities as travel destinations of the international demi-monde and gay sub-culture at the end of the Nineteenth and beginning of the Twentieth Century, which included such illustrious travellers as Oscar Wilde and "Bosie", among others. Richly illustrated, including many antiquarian postcards, point at the lost glory of cities such as Algiers and Biskra under French colonial rule. Some of the descriptions are also reminiscent of Albert Camus descriptions of Oran.

Especially in the first part of the book, Arabesques. A tale of double lives is slightly marred by some narrative techniques used by the author. In the first two or three chapters, there are multiple repetitions of the suggestion that Gide's life would all have been very different if, at paying his hotel bill in Blidah he would have "glanced to the left instead of to the right." Throughout the book there are many references to "Jacoub", one of Dessaix's guide in Algeria whom he portrays very unsympathetically. Maps at the beginning of the book suggest that the journey, followed tracing Gide's steps will lead through various countries, including Spain, Portugal and Italy, while in fact very little attention is paid to these countries. A whole chapter is devoted to Morocco, which seems much more relevant in the life of Dessaix than in the life of André Gide.

Other books I have read by Robert Dessaix:

Corfu

Finished reading: 9 January 2013

Boys as dark as violets

Arabesques. A tale of double lives is Robert Dessaix' very personal, and very subjective biography of André Gide. In fact, it is more of a kaleidoscopic travelogue than a biography. The subtitle A tale of double lives refers as much to the double lives led by Gide, as well as the intertwined exploration of the parallels and contrasts between the lives of Gide and the author. In the absence of a clear chronologie, the book has a dream-like quality of preponderences on the life of André Gide and its author Robert Dessaix, as Dessaix retraces Gide's steps in his travels all over the Western Mediterranean, with particular attention to North Africa, as chapter titles suggest visits to Algiers, Blidah, Tornac, Anduze, Morocco, Cuverville (France), Sousse and Biskra.

Without overmuch emphasis, Dessaix clearly emerges from the narrative as a very seasoned, and openly gay person, whose promiscuity may have been tempered with age. On the other hand, Dessaix portrays Gide as a very timid and closeted homosxual, who may not even have considered himself gay, and whose adoration of boys and young men verged on Platonic aestheticism. However, it is clear that Dessaix rejects that image. At the same time, the author seems to be at a loss to explain the apparent lifelong devotion of Gide for his cousin Madeleine, whom he married at a very young age, and is said to have truly and deeply loved. This contrast, the suggestion that Gide came to homosexuality after meeting Oscar Wilde and subsequently lived as a completely repressed homosexual, who may have truly loved his wife, seems to be a construct in the mind of Dessaix which is not really born out by autobiographical facts.

An interesting aspect of Arabesques. A tale of double lives is that it uncovers the history of various Algerian cities as travel destinations of the international demi-monde and gay sub-culture at the end of the Nineteenth and beginning of the Twentieth Century, which included such illustrious travellers as Oscar Wilde and "Bosie", among others. Richly illustrated, including many antiquarian postcards, point at the lost glory of cities such as Algiers and Biskra under French colonial rule. Some of the descriptions are also reminiscent of Albert Camus descriptions of Oran.

Especially in the first part of the book, Arabesques. A tale of double lives is slightly marred by some narrative techniques used by the author. In the first two or three chapters, there are multiple repetitions of the suggestion that Gide's life would all have been very different if, at paying his hotel bill in Blidah he would have "glanced to the left instead of to the right." Throughout the book there are many references to "Jacoub", one of Dessaix's guide in Algeria whom he portrays very unsympathetically. Maps at the beginning of the book suggest that the journey, followed tracing Gide's steps will lead through various countries, including Spain, Portugal and Italy, while in fact very little attention is paid to these countries. A whole chapter is devoted to Morocco, which seems much more relevant in the life of Dessaix than in the life of André Gide.

Other books I have read by Robert Dessaix:

Corfu

42dmsteyn

Gide interests me, and this book seems intriguing as well. I was a bit surprised that you gave it 4 ½ stars, especially considering the criticisms in the last paragraph.

43edwinbcn

>

My appreciation for Arabesques. A tale of double lives increased with reading, although the problems described in the last part of my review, occurring in the first few chapters actually irritated me very much.

However, on the whole, the book has a very ejoyable poetic quality that is borne out as one reads more. The Picador first edition paperback's paper quality is, unfortunately, not very high, but the rich illustrations, and the fairly large size of the book, make for a really nice reading experience.

The high degree of subjectivity make the book quasi intimate. It is possible that these tricks are used by the author to stimulate the readers' imagination. Without annotation is is hard to make out what is factual about Gide North-African adventures. Dessaix in clearly well-informed about the life of André Gide, but, typically, some details of what could have happened usually are not included in biographical accounts or even primary sources. Therefore, Arabesques. A tale of double lives substitutes fact with some speculation and quite a lot of suggestiveness. This is a feature that makes the book attractive, although perhaps not to every type of reader. The book is probably somewhat more appealing to gay readership.

Another thing I really liked about the book was how, as a travel memoir, it introduced various cities in Algeria and North-African culture, which formed a nice complementary experience to my reading of essays from Noces (English tr. Nuptials) by Albert Camus.

My appreciation for Arabesques. A tale of double lives increased with reading, although the problems described in the last part of my review, occurring in the first few chapters actually irritated me very much.

However, on the whole, the book has a very ejoyable poetic quality that is borne out as one reads more. The Picador first edition paperback's paper quality is, unfortunately, not very high, but the rich illustrations, and the fairly large size of the book, make for a really nice reading experience.

The high degree of subjectivity make the book quasi intimate. It is possible that these tricks are used by the author to stimulate the readers' imagination. Without annotation is is hard to make out what is factual about Gide North-African adventures. Dessaix in clearly well-informed about the life of André Gide, but, typically, some details of what could have happened usually are not included in biographical accounts or even primary sources. Therefore, Arabesques. A tale of double lives substitutes fact with some speculation and quite a lot of suggestiveness. This is a feature that makes the book attractive, although perhaps not to every type of reader. The book is probably somewhat more appealing to gay readership.

Another thing I really liked about the book was how, as a travel memoir, it introduced various cities in Algeria and North-African culture, which formed a nice complementary experience to my reading of essays from Noces (English tr. Nuptials) by Albert Camus.

44Rise

I'm very curious about Alfred Andersch's memoirs and the conclusions it gave. I read a very critical essay on him by W. G. Sebald in On the Natural History of Destruction.

45baswood

Edwin, you have read some very interesting books lately and made some very fine reviews. I will pass on The Forgotten Waltz because the main character would annoy me too much, Although I am intrigued by your comparison to What Maisie Knew

For who is ever truly free from fear or duty Well stated Edwin, I am sure I have rarely been. That was a fascinating review of The Cherries of Freedom

The book that really interests me is Arabesques: A tale of double lives, which goes straight onto my to buy list.

For who is ever truly free from fear or duty Well stated Edwin, I am sure I have rarely been. That was a fascinating review of The Cherries of Freedom

The book that really interests me is Arabesques: A tale of double lives, which goes straight onto my to buy list.

46edwinbcn

Thanks, Barry. Actually, I haven't read What Masie knew and my comparison and suggestions in relation to The forgotten waltz are mainly based on ideas you expressed in your review, which was posted around the same time. I was tempted to read What Masie knew at that time, but have to postpone that to some later date.

47edwinbcn

>44 Rise:

Yes, Rise, the essay by W.G. Sebald in On the Natural History of Destruction basically started the controversy around Alfred Andersch. That essay, "Between the devil and the deep blue sea. Alfred Andersch. Das Verschwinden in der Vorsehung" was first published in 1993. It was then included in the German first edition of Luftkrieg und Literatur: Mit einem Essay zu Alfred Andersch, This book was later published in a slightly different form and expanded to include two more essays as On the natural History of Destruction: With Essays on Alfred Andersch, Jean Améry and Peter Weiss (English trans. Anthea Bell (2003).

Sebald's essay marks the beginning of a 20-year controversy around the moral integrity of the German author Alfred Andersch, among others. This controversy has not been concluded.

Anyone interested to read postwar German literature, written by authors who were basically aged 18 before 1944, and may or may not have been active as writers during the period of the Third Reich, while not living in exile, should be aware of possible controversy around their authorship and moral integrity. Similar debates regularly flare up over other German authors belonging to that generation, and many of these controversies started or were refueled by new, recent discoveries in the 1990s or even through to the present, as I showed in my reviews of autobiographical work of Luise Rinser in various reviews last year. These controversies and attacks have bothered the Nobel Prize winner Günter Grass as well as several other members of the socalled Gruppe 47 (Engl. "Group 47", originally founded by Alfred Andersch, and others such as Wolfgang Koeppen, Christa Wolf, Peter Huchel, Günter Eich and Martin Walser.

The controversy around Alfred Andersch relates in particular to his representation of the facts around his marriage, and the suggested strategic use of that marriage to his own advantages. Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom) takes a key position in that debate, with Rolf Seubert claiming that, after detailed analysis of the manuscript and external documents "in „Kirschen der Freiheit“ kaum ein Detail mit den Quellen und Berichten übereinstimme." (hardly any detail corresponds with the sources). These details relate to Andersch position in the Communist youth organization, the duration of his imprisonment in concentration camp Dachau, factual observations in Dachau, his release from the German army, his marriage and anullment thereof and his status as a POW in 1944.

The main discussion, and the issue or moral integrity, raised by W.G. Sebald is about his marriage. In 1935, Alfred Andersch married Angelika Albert, who was half-Jewish. Conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht) in 1940, Andersch met and fell in love with Gisela Groneuer while he was on leave in the autumn of 1940. In March 1941, Andersch was released from the army. Andersch claims that his request for release was based on his imprisonment in Dachau, but such imprisonment could not form a ground for release. In fact, reference to that imprisonment would have made his situation worse. In 2008, it was proved that Andersch requested release on the ground of being married with his half-Jewish wife. This release was enabled through the Nürnberger Gesetze (Nürnberg Laws) which forbade conscription of soldiers into the Wehrmacht who were married to partners who were not Arian (Angelika was classified as mixed blood of the first degree). Although his mother-in-law was deported, Angelika and their daughter was apparently and eventually not exposed to any danger. German citizens of mixed ancestry were never persecuted or deported, and were not treated in the way Jewish citizens were.

In the course of 1941, Andersch started an affair with Gisela, with whom he had a baby, and lived separately from his wife from 1942 onwards. Encouraged in his career as an author by Gisela, Andersch applied for the right to publish his work in Germany in 1943. To obtain this right he had to divorce Angelika. In his application he told the commission that he had already divorced from Angelika, which was factaully not true. The actual divorce came through later in 1943. This is supposedly the second case in which Andersch made strategic use of his marriage to Angelika to his own advantage.

As a result of the divorce, Andersch was again conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht). Following his desertion from the army, described in Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom) was captured and locked up as a POW by the Americans in Italy in 1944. During this imprisonment, Andersch claimed to be married to Angelika. This claim constitutes the third time he made strategic use of the marriage to Angelika Albert, as marriage to a "Jewish mongrel" helped him secure his earlier release and the release of his manuscripts which had been confiscated. After the war, Andersch married Gisela.

Throughout the controversy about Alfred Andersch moral integrity, the moral integrity of W.G. Sebald was equally disputed, as Sebald's claims in 1993 were based on very scanty and inconclusive evidence. Sebald's accusations were later strengthened by new discoveries in 2008. However, Alfred Andersch biographer Stephan Reinhardt, in Alfred Andersch. Eine Biographie had already suggested that Andersch marriage to Angelika had floundered. To many, Sebald's position resembles more that of a troublemaker, who did not do sufficient research, and would possibly benefit from the exposure.

The Alfred Andersch controversy is not a small matter. The debate has raged for more than 20 years, since the publication of Reinhardt's biography in 1990 and Sebald's essay in 1993. Several books have been published about it, notably following a conference on the issue in 2010 and Alfred Andersch 'revisited'. Werkbiographische Studien im Zeichen der Sebald-Debatte (2011) by Jörg Döring and Markus Joch (Eds).

The controversy is no longer merely about "proof". In matters of moral integrity over Andersch marriage, it seems the reader must decide which version to believe (with Andersch biographer, who believes the marriage was at an end). In Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom), Alfred Andersch has already convincingly argued that fear limits freedom and makes people make choices and do things they would or might not otherwise.

With regard to Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom), it needs to be seen to what extent this work is autobiographical.

Yes, Rise, the essay by W.G. Sebald in On the Natural History of Destruction basically started the controversy around Alfred Andersch. That essay, "Between the devil and the deep blue sea. Alfred Andersch. Das Verschwinden in der Vorsehung" was first published in 1993. It was then included in the German first edition of Luftkrieg und Literatur: Mit einem Essay zu Alfred Andersch, This book was later published in a slightly different form and expanded to include two more essays as On the natural History of Destruction: With Essays on Alfred Andersch, Jean Améry and Peter Weiss (English trans. Anthea Bell (2003).

Sebald's essay marks the beginning of a 20-year controversy around the moral integrity of the German author Alfred Andersch, among others. This controversy has not been concluded.

Anyone interested to read postwar German literature, written by authors who were basically aged 18 before 1944, and may or may not have been active as writers during the period of the Third Reich, while not living in exile, should be aware of possible controversy around their authorship and moral integrity. Similar debates regularly flare up over other German authors belonging to that generation, and many of these controversies started or were refueled by new, recent discoveries in the 1990s or even through to the present, as I showed in my reviews of autobiographical work of Luise Rinser in various reviews last year. These controversies and attacks have bothered the Nobel Prize winner Günter Grass as well as several other members of the socalled Gruppe 47 (Engl. "Group 47", originally founded by Alfred Andersch, and others such as Wolfgang Koeppen, Christa Wolf, Peter Huchel, Günter Eich and Martin Walser.

The controversy around Alfred Andersch relates in particular to his representation of the facts around his marriage, and the suggested strategic use of that marriage to his own advantages. Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom) takes a key position in that debate, with Rolf Seubert claiming that, after detailed analysis of the manuscript and external documents "in „Kirschen der Freiheit“ kaum ein Detail mit den Quellen und Berichten übereinstimme." (hardly any detail corresponds with the sources). These details relate to Andersch position in the Communist youth organization, the duration of his imprisonment in concentration camp Dachau, factual observations in Dachau, his release from the German army, his marriage and anullment thereof and his status as a POW in 1944.

The main discussion, and the issue or moral integrity, raised by W.G. Sebald is about his marriage. In 1935, Alfred Andersch married Angelika Albert, who was half-Jewish. Conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht) in 1940, Andersch met and fell in love with Gisela Groneuer while he was on leave in the autumn of 1940. In March 1941, Andersch was released from the army. Andersch claims that his request for release was based on his imprisonment in Dachau, but such imprisonment could not form a ground for release. In fact, reference to that imprisonment would have made his situation worse. In 2008, it was proved that Andersch requested release on the ground of being married with his half-Jewish wife. This release was enabled through the Nürnberger Gesetze (Nürnberg Laws) which forbade conscription of soldiers into the Wehrmacht who were married to partners who were not Arian (Angelika was classified as mixed blood of the first degree). Although his mother-in-law was deported, Angelika and their daughter was apparently and eventually not exposed to any danger. German citizens of mixed ancestry were never persecuted or deported, and were not treated in the way Jewish citizens were.

In the course of 1941, Andersch started an affair with Gisela, with whom he had a baby, and lived separately from his wife from 1942 onwards. Encouraged in his career as an author by Gisela, Andersch applied for the right to publish his work in Germany in 1943. To obtain this right he had to divorce Angelika. In his application he told the commission that he had already divorced from Angelika, which was factaully not true. The actual divorce came through later in 1943. This is supposedly the second case in which Andersch made strategic use of his marriage to Angelika to his own advantage.

As a result of the divorce, Andersch was again conscripted into the German army (Wehrmacht). Following his desertion from the army, described in Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom) was captured and locked up as a POW by the Americans in Italy in 1944. During this imprisonment, Andersch claimed to be married to Angelika. This claim constitutes the third time he made strategic use of the marriage to Angelika Albert, as marriage to a "Jewish mongrel" helped him secure his earlier release and the release of his manuscripts which had been confiscated. After the war, Andersch married Gisela.

Throughout the controversy about Alfred Andersch moral integrity, the moral integrity of W.G. Sebald was equally disputed, as Sebald's claims in 1993 were based on very scanty and inconclusive evidence. Sebald's accusations were later strengthened by new discoveries in 2008. However, Alfred Andersch biographer Stephan Reinhardt, in Alfred Andersch. Eine Biographie had already suggested that Andersch marriage to Angelika had floundered. To many, Sebald's position resembles more that of a troublemaker, who did not do sufficient research, and would possibly benefit from the exposure.

The Alfred Andersch controversy is not a small matter. The debate has raged for more than 20 years, since the publication of Reinhardt's biography in 1990 and Sebald's essay in 1993. Several books have been published about it, notably following a conference on the issue in 2010 and Alfred Andersch 'revisited'. Werkbiographische Studien im Zeichen der Sebald-Debatte (2011) by Jörg Döring and Markus Joch (Eds).

The controversy is no longer merely about "proof". In matters of moral integrity over Andersch marriage, it seems the reader must decide which version to believe (with Andersch biographer, who believes the marriage was at an end). In Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom), Alfred Andersch has already convincingly argued that fear limits freedom and makes people make choices and do things they would or might not otherwise.

With regard to Die Kirschen der Freiheit (Cherries of Freedom), it needs to be seen to what extent this work is autobiographical.

48dmsteyn

Thanks for the fascinating insight into the Andersch controversy, Edwin. I wasn't aware of it at all, but I'll definitely keep it in mind when I get to Die Kirschen der Freiheit. The ambiguities make me somewhat uncomfortable, I'll admit. That said, we are dealing with living human beings here, so some ambiguities, even falsehoods, might be expected. Not having lived Andersch's experiences, I won't condemn him solely based on this.

49Rise

Thanks, edwin. That was a comprehensive summary of the literary controversy. I have to admit I was also turned off with Andersch when I read Sebald's essay on him.

50deebee1

Very interesting stuff here, edwin. I'm interested to read Cherries of Freedom as the author is from Germany's post war period which I have a mini-theme read on this year. I know almost nothing of the works of the Gruppe 47, except of Wolfgang Koeppen's (which I like very much), so I appreciate learning about this book, including the controversies surrounding it, which means a measure of skepticism is required in its reading.

51edwinbcn

009. Goethe's Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde